Koto

Plucked Instruments

Asia

Between 0 and 1000 AD

Video

The koto, a quintessential Japanese stringed musical instrument, embodies a rich history and captivating sound that has resonated through centuries. Its presence in Japanese culture is profound, extending beyond mere musical performance to encompass artistic expression, spiritual significance, and social interaction. Understanding the koto requires delving into its multifaceted nature, from its physical construction to its historical evolution and diverse musical applications.

Description and Type of Instrument

The koto is a plucked zither, characterized by its long, convex body crafted from paulownia wood.

Its strings, traditionally made of silk, are stretched across movable bridges known as ji, allowing for precise tuning and tonal variations. Players utilize ivory or plastic plectra, called tsume, worn on the thumb, index, and middle fingers of the right hand to pluck the strings. The left hand manipulates the strings by pressing or pulling them, creating vibrato and pitch alterations. The koto’s sound is distinctive, often described as serene, melancholic, and evocative, reflecting the nuances of Japanese aesthetics. The instrument’s visual elegance is as striking as its auditory qualities, with its polished wood, intricate inlays, and graceful curves contributing to its overall artistic appeal. The koto’s primary function is to produce melodic and harmonic sounds, whether in solo performances, ensemble pieces, or as an accompaniment to vocal music. Its versatility allows it to adapt to various musical genres, from traditional court music to contemporary compositions.

Historical Background

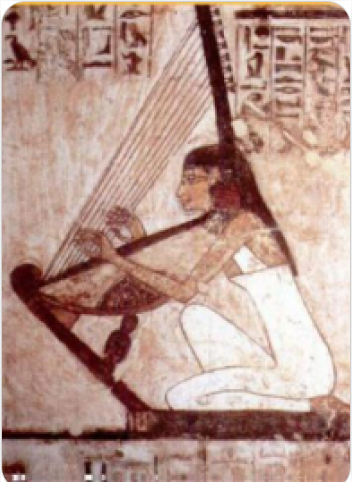

The koto’s origins can be traced back to China, where a similar instrument known as the guzheng existed as early as the Zhou Dynasty (1122-256 BC). The instrument’s journey to Japan occurred during the Nara period (710-794 AD), likely through diplomatic and cultural exchanges with the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD). Initially, the koto, then known as the gakuso, was primarily used in gagaku, the ancient court music of Japan. It was an integral part of the imperial orchestra, contributing to the solemn and refined atmosphere of court ceremonies. Over time, the koto gradually permeated other social strata, becoming a popular instrument among the aristocracy and eventually finding its way into the homes of commoners. During the Heian period (794-1185 AD), the koto’s popularity soared, with noblewomen often learning to play it as a refined accomplishment. The instrument’s role expanded beyond court music, featuring in narrative performances and accompanying vocal pieces. The development of distinct koto schools and styles began to emerge in the Edo period (1603-1868 AD), marking a significant shift from its exclusive association with the court. The influence of blind musicians, particularly Yatsuhashi Kengyo, who is considered the father of modern koto music, was instrumental in this transformation. He standardized the tuning and developed new techniques, laying the foundation for the flourishing of koto music in the broader society. The Meiji Restoration (1868-1912 AD) brought about modernization and Westernization, but the koto managed to retain its cultural significance. Composers began to incorporate Western musical elements into koto compositions, creating a fusion of traditional and contemporary styles. In the 20th and 21st centuries, the koto has continued to evolve, with composers exploring new possibilities and techniques, ensuring its relevance in the modern musical landscape. Its journey, spanning over a millennium, reflects the enduring appeal and adaptability of this iconic instrument.

Construction and Design

The construction of a koto is a meticulous and time-honored process, requiring skilled craftsmanship and specialized knowledge. The primary material used is paulownia wood, known as kiri in Japanese, prized for its lightweight, resonant, and beautiful grain. The process begins with selecting and seasoning the wood, which can take several years. The wood is then carefully shaped and hollowed out to create the instrument’s distinctive convex body. The top surface of the koto, known as the ita, is typically left unadorned, allowing the natural beauty of the wood to shine through. The underside, or ura, may be carved with intricate patterns or left plain. The strings, traditionally made of silk, are stretched across the ita and secured at both ends. The bridges, or ji, are placed along the ita, supporting the strings and allowing for precise tuning. These bridges are typically made of ivory or plastic and can be moved to adjust the pitch of each string. The tsume, or plectra, worn on the fingers, are essential tools for playing the koto. They are traditionally made of ivory, but plastic versions are now more common. The design of the koto reflects a balance between functionality and aesthetics. The instrument’s graceful curves, polished surfaces, and intricate details contribute to its overall visual appeal. The placement of the bridges and the spacing of the strings are carefully calculated to ensure optimal sound production. The size and shape of the koto can vary slightly depending on the style and intended use, but the fundamental design remains consistent. The length of a standard koto is approximately 180 centimeters, with 13 strings. The wood of the koto is treated with great care, as it is believed to improve with age, enhancing the instrument’s tonal quality. The construction and design of the koto are deeply rooted in tradition, with each element contributing to the instrument’s unique sound and visual elegance.

Types of Koto

While the standard koto with 13 strings is the most common, there are several variations that cater to different musical styles and performance needs. One notable variation is the so-no-koto, which is the standard 13-string koto used in traditional music. Then there is the 17-string koto, or jūshichigen, which was developed in the early 20th century by Michio Miyagi. It has a deeper, more resonant sound and is often used in contemporary compositions. The 21-string koto, or nijūichigen, represents a further expansion of the instrument’s range, providing even greater tonal possibilities for modern composers. Other Koto types include smaller sized koto for childrens practice, and also electric koto. In older Japanese history, Koto with other numbers of strings were also used, that are rarely, if ever played now. The 17-string koto is frequently employed in ensemble settings, particularly in conjunction with the standard koto and shakuhachi, a bamboo flute. Its deeper tones create a rich harmonic foundation, complementing the melodic lines of the other instruments. The 21-string koto takes this concept even further, offering a wider spectrum of sound that can be used to create complex textures and harmonies. Modern composers have embraced the expanded range of these variations, pushing the boundaries of koto music and exploring new sonic possibilities. The use of these variations allows for a greater variety of musical textures, tonalities, and melodic ideas. The development of these different types of koto demonstrates the adaptability of the instrument and its ability to evolve alongside changing musical tastes and technological advancements.

Characteristics

The koto possesses a unique set of characteristics that contribute to its distinctive sound and cultural significance. One of its defining features is its tonal quality, which is often described as serene, melancholic, and evocative. The silk strings, when plucked with the ivory tsume, produce a delicate and resonant sound that can evoke a wide range of emotions. The movable bridges allow for precise tuning and the creation of various scales and modes, adding to the instrument’s versatility. The left-hand techniques, such as pressing and pulling the strings, create vibrato and pitch alterations, enriching the expressive possibilities of the koto. The instrument’s visual elegance is another essential characteristic. The polished paulownia wood, intricate inlays, and graceful curves contribute to its overall aesthetic appeal. The koto’s design reflects a balance between functionality and artistry, with each element carefully considered to enhance both its sound and appearance. The koto is also characterized by its association with traditional Japanese culture and aesthetics. It has been an integral part of court music, narrative performances, and traditional ceremonies for centuries, embodying the values of harmony, refinement, and contemplation. The koto’s role in Japanese society extends beyond mere musical performance. It is often used as a tool for self-cultivation and spiritual development, fostering a sense of inner peace and tranquility. The practice of koto playing is considered a refined art, requiring dedication, discipline, and a deep understanding of Japanese musical traditions. The instrument’s ability to evoke a wide range of emotions makes it a powerful tool for artistic expression. Its rich history and cultural significance contribute to its enduring appeal, ensuring its continued presence in the Japanese musical landscape. The Koto, through all these charcteristics, has obtained a place in the heart of Japanese culture.

Playing Techniques and Sound Modifications

The koto, a long, 13-stringed zither, is played with plectra called tsume, which are worn on the thumb, index, and middle fingers of the right hand. These tsume, traditionally made of ivory, though now often of plastic, allow for precise plucking of the strings. Basic playing involves plucking individual strings to create melodic lines. However, the koto’s versatility extends far beyond simple melodies. A fundamental technique is oshi-zume, which involves pressing down on the strings to the left of the bridges, altering the pitch and creating vibrato or glissando effects. This technique is crucial for achieving the characteristic melodic inflections and expressive nuances found in traditional koto music. The left hand plays a significant role in manipulating the strings, primarily for pitch bending and creating ornamentation.

Oshi-zume can be used to create a wide range of tonal colors, from subtle vibrato to dramatic pitch shifts. Another essential technique is hikizume, where the string is pulled or plucked upwards, creating a different timbre and attack. This technique is often used to add rhythmic accents or to create a more percussive sound. The interplay between oshi-zume and hikizume, combined with various plucking patterns, allows for a rich and varied musical expression. Melodic phrases are often embellished with delicate ornaments, such as kobushi, a type of melodic turn, and yurashi, a gentle vibrato. These ornaments add depth and complexity to the music, reflecting the refined aesthetic of traditional Japanese music. The use of different plucking angles and strengths also contributes to the koto’s expressive range. A softer pluck produces a gentle, mellow tone, while a stronger pluck creates a brighter, more resonant sound. The player can also vary the position of the tsume on the string to alter the timbre. Plucking closer to the bridge produces a sharper, more metallic sound, while plucking closer to the center of the string creates a warmer, more mellow tone. Beyond these fundamental techniques, koto players often employ advanced techniques to create unique sound effects.

These include dan-zume, a technique where the strings are plucked in rapid succession to create a cascading effect, and kake-zume, where the string is plucked and then immediately dampened to create a percussive sound. The use of harmonics, achieved by lightly touching the string at specific points, adds another dimension to the koto’s sonic palette. Furthermore, contemporary koto players often experiment with extended techniques, such as using bows or other objects to create unconventional sounds. Electronic effects, such as reverb and delay, are also sometimes used to further expand the koto’s sonic possibilities. The use of different tunings, or chōshi, also significantly impacts the koto’s sound. The most common tuning is hirajōshi, but other tunings, such as kumoi-jōshi and akita-chōshi, are used to create different moods and musical contexts. These tunings are achieved by adjusting the movable bridges, allowing for a wide range of tonal colors and harmonic possibilities.

Applications in Music

The koto has a rich and diverse history in Japanese music, spanning centuries and encompassing various genres. In traditional Japanese music, the koto plays a central role in gagaku, the ancient court music, where it contributes to the majestic and solemn soundscape. It is also a key instrument in sōkyoku, a genre of chamber music that flourished during the Edo period. Sōkyoku often features vocal accompaniment, with the koto providing melodic and harmonic support. The koto is also featured in jiuta, a genre of lyrical songs that often depict scenes from nature or evoke emotional landscapes. In these traditional settings, the koto is often performed alongside other instruments, such as the shamisen and shakuhachi, creating a rich and textured ensemble sound. Beyond traditional music, the koto has found a place in contemporary music, both within Japan and internationally. Japanese composers have incorporated the koto into modern classical compositions, exploring its expressive potential in new and innovative ways. The koto has also been used in jazz, pop, and experimental music, often fused with Western musical styles. In film soundtracks, the koto’s distinctive sound can create a sense of Japanese cultural identity or evoke a specific mood or atmosphere. In contemporary settings, the koto is sometimes used in solo performances, showcasing its versatility and expressive range. Koto ensembles, consisting of multiple koto players, create a rich and complex sonic texture.

The koto’s adaptability has allowed it to transcend its traditional boundaries and find a place in a wide range of musical contexts. Its unique sound and expressive capabilities continue to inspire composers and musicians around the world. The koto is used in educational settings, both in Japan and internationally, to teach about Japanese culture and music. Many schools and universities offer koto lessons, and there are numerous koto societies and organizations dedicated to promoting the instrument. The koto is also used in therapeutic settings, such as music therapy, where its calming and meditative sound can have a positive impact on mental and emotional well-being. The instrument has also been used in cross-cultural collaborations, bringing together musicians from different backgrounds to create new and innovative musical experiences.

Most Influential Players

Throughout its long history, numerous koto players have made significant contributions to the development and evolution of the instrument. Yatsuhashi Kengyo (1614-1685) is considered one of the most influential figures in the history of koto music. He is credited with standardizing the hirajōshi tuning and composing many of the classic sōkyoku pieces. Ikuta Kengyo (1656-1715) founded the Ikuta school of koto, which emphasized vocal accompaniment and the integration of koto with shamisen and shakuhachi. Yamada Kengyo (1757-1817) founded the Yamada school of koto, which focused on expressive melodies and dramatic performance techniques. These schools have had a profound impact on the development of koto music and continue to influence koto players today. Michio Miyagi (1894-1956) was a blind koto player and composer who revolutionized koto music in the 20th century. He composed numerous innovative pieces that incorporated Western musical elements and expanded the koto’s expressive range. His works, such as “Haru no Umi” (Spring Sea), are widely recognized and continue to be performed today. Tadao Sawai (1937-1997) was a renowned koto player and composer who explored the possibilities of contemporary koto music. He collaborated with musicians from various genres and composed numerous pieces that pushed the boundaries of traditional koto music. Kazue Sawai, his wife, is also a highly respected koto performer and teacher, continuing to expand the koto’s repertoire and influence. Reiko Takahashi is a contemporary koto player known for her innovative performances and collaborations with musicians from diverse backgrounds. She has played a large role in bringing the koto to a wider, international audience. These players, among many others, have played a vital role in shaping the koto’s history and ensuring its continued relevance in the contemporary music world.

Maintenance and Care

The koto, being a delicate instrument, requires careful maintenance and care to ensure its longevity and optimal performance. The strings, traditionally made of silk, are susceptible to damage from humidity and temperature fluctuations. Modern strings are often made of nylon or other synthetic materials, which are more durable but still require regular maintenance. The bridges, which support the strings, should be checked regularly for proper placement and stability. The body of the koto, typically made of paulownia wood, should be cleaned with a soft cloth to remove dust and fingerprints. It is essential to protect the koto from extreme temperatures and humidity, as these can cause warping and cracking. When not in use, the koto should be stored in a protective case to prevent damage. Regular tuning is essential for maintaining the koto’s pitch and sound quality. The tsume, or plectra, should also be cleaned and stored properly to prevent damage. The koto should be inspected regularly by a qualified luthier to identify and address any potential problems. Proper maintenance and care will ensure that the koto remains in good condition and continues to produce its beautiful sound for many years to come.

Cultural Significance

The koto holds a deep and multifaceted cultural significance in Japan. It is not merely a musical instrument but also a symbol of Japanese tradition, refinement, and aesthetic values. The koto’s association with the imperial court and aristocratic culture has imbued it with a sense of elegance and prestige. Its delicate and refined sound is often associated with the beauty of nature and the changing seasons, reflecting the Japanese appreciation for harmony and balance. The koto is often featured in traditional Japanese arts, such as poetry, literature, and painting, further reinforcing its cultural significance. The koto is also associated with the concept of wa, or harmony, which is a fundamental principle in Japanese culture. The koto’s ensemble playing, where multiple instruments blend together to create a unified sound, embodies this concept of harmony. The koto is also a symbol of feminine grace and refinement, as it was traditionally played by women in the imperial court and aristocratic households. The koto is often used in traditional ceremonies and rituals, such as weddings and funerals, adding a sense of solemnity and reverence. The koto’s presence in contemporary Japanese culture, both in traditional and modern music, demonstrates its enduring relevance and cultural significance.

FAQ

What are the main features of the Koto?

The Koto is a traditional Japanese stringed instrument with a long, hollow wooden body. It typically has 13 silk or synthetic strings, each supported by movable bridges. The instrument is played using fingerpicks called "tsume" and produces a soft, resonant sound. Modern variants can have 17 or more strings.

What materials are used to construct a Koto?

Traditional Kotos are crafted from Paulownia wood, known for its light weight and excellent resonance. The strings were historically made of silk but are now often synthetic for durability. Bridges are typically made from ivory, plastic, or wood. Some Kotos have lacquer or inlays for decorative appeal.

How is the Koto used in music?

The Koto is widely used in traditional Japanese music, court music (Gagaku), and contemporary compositions. It is featured in ensembles, solo performances, and modern fusion genres. The instrument’s tuning can be adjusted for different scales, making it versatile for various musical styles.

Links

Links

References

- Koto: The National Musical Instrument of Japan

- Koto (Instrument) - Wikipedia

- Koto: The Sound of Traditional Japanese Courts

- Koto | Japanese, 13-string, zither | Britannica

- Koto is a traditional Japanese musical instrument and a popular choice for court music

- Koto Performance by ENOKIDO Fuyuki | Japan House London

Other Instrument

Categories