Setar

Plucked Instruments

Asia

Between 1001 and 1900 AD

Video

The Setar, a cherished instrument in Iranian musical tradition, stands out for its subtlety, expressiveness, and deep spiritual resonance. Its name, derived from Persian, literally means “three strings”—‘se’ for three and ‘tar’ for string—though the modern Setar features four strings. The instrument’s design is understated, with a compact, pear-shaped body and a long, slender neck, giving it an elegant and unobtrusive appearance. This simplicity, however, belies the instrument’s profound capacity for emotional expression, making it a favorite among solo performers and Sufi mystics alike. The Setar’s sound is gentle, intimate, and ethereal, capable of expressing a wide range of moods, from meditative introspection to subtle joy.

The Setar is classified as a plucked string instrument, specifically a long-necked lute. It belongs to the broader family of chordophones, which produce sound through the vibration of stretched strings. Within this family, the Setar is closely related to other Persian lutes such as the Tar and the Tanbur, sharing similarities in construction and playing technique. However, the Setar distinguishes itself through its smaller body, lighter construction, and unique playing style. Traditionally, the instrument had three strings, but a fourth string was added in the 19th century, expanding its range and versatility. The Setar is typically tuned to various scales (dastgahs) used in Persian music, allowing for a rich palette of melodic possibilities. The instrument’s frets are movable, enabling the performer to adjust the tuning to accommodate different modes and microtonal intervals characteristic of Persian music.

History of the Setar

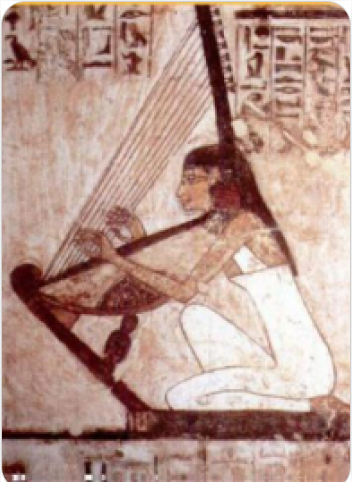

The Setar’s origins can be traced back several centuries to the Persian cultural sphere, which encompasses modern-day Iran and neighboring regions. Its development is closely linked to the evolution of Persian music and the broader tradition of long-necked lutes in Central Asia and the Middle East. The instrument is believed to have emerged from the Tanbur family, a group of ancient lutes that have been played in the region for millennia. The earliest versions of the Setar likely appeared during the medieval period, though the instrument as it is known today began to take shape during the Safavid (16th–18th centuries) and Qajar (18th–20th centuries) dynasties in Iran. It was during the Qajar era that the Setar underwent significant modifications, most notably the addition of a fourth string by the mystic Moshtagh Ali Shah in the 19th century. This innovation expanded the instrument’s sonic possibilities and solidified its place in Persian classical music. The Setar has long been associated with Sufi mysticism, serving as a vehicle for spiritual expression and meditation. It was commonly played in Sufi gatherings, known as khaneqahs, where its gentle tones were believed to facilitate spiritual elevation and communion. Over time, the Setar became an integral part of Persian musical culture, revered for its ability to convey the subtleties of Persian poetry and the complexities of the dastgah system. Its influence extended beyond Iran, with regional variations appearing in Azerbaijan, Kurdistan, and other neighboring areas. The Setar’s enduring popularity is a testament to its adaptability and expressive power, qualities that have allowed it to remain relevant in both traditional and contemporary musical contexts.

Construction and Physical Structure

The Setar’s construction reflects a harmonious blend of simplicity and craftsmanship. The instrument typically measures around 80–85 centimeters in length, with a body width of approximately 16–17 centimeters and a depth of 13–14 centimeters. The body, or bowl, is usually carved from a single piece of mulberry wood, chosen for its resonant qualities and durability. In some cases, cherry, walnut, or pear wood may also be used, each imparting subtle differences in tone and appearance. The bowl is pear-shaped and semi-spherical, providing a compact yet resonant chamber for sound production. The neck is long and slender, often made from walnut wood, and is attached to the body with precision to ensure stability and playability. The fingerboard features 24 to 26 movable frets, traditionally made from animal gut but now often crafted from nylon or other synthetic materials. These frets are tied around the neck and can be adjusted to accommodate the microtonal intervals characteristic of Persian music. The Setar’s four strings are typically made of steel or brass, though earlier versions used silk or gut. The strings are arranged in two pairs, with the bottom two usually played together to create a fuller sound.

The tuning pegs are located at the end of the neck, allowing for precise adjustment of string tension. The bridge, positioned on the soundboard, transmits the vibrations of the strings to the body, amplifying the instrument’s delicate sound. The Setar is played by plucking the strings with the nail of the right index finger, a technique that requires both dexterity and sensitivity. The left hand presses the strings against the frets to produce different pitches, with subtle ornamentations and slides adding to the instrument’s expressive palette. The overall design of the Setar prioritizes portability, ease of play, and tonal clarity, making it accessible to musicians of all levels while retaining the depth and complexity required for advanced performance.

Types of Setar

While the Setar is most commonly associated with Persian classical music, there are several regional and stylistic variations of the instrument, each with its own unique characteristics. The Persian Setar, which serves as the standard model, is widely used throughout Iran and forms the basis for most contemporary performances. It is characterized by its four-string configuration, movable frets, and pear-shaped body. In addition to the Persian Setar, there are Azerbaijani and Kurdish versions of the instrument, each reflecting the musical traditions and preferences of their respective regions. The Azerbaijani Setar, for example, may feature variations in body shape, string arrangement, and tuning, while the Kurdish Setar often incorporates different playing techniques and repertoires. Within Iran itself, Setars are made in various sizes and shapes, including large, small, flat, and zir-abai models. The method of construction can also vary, with some Setars made using the Turkish method (assembled from multiple pieces) and others crafted from a single piece of wood (scraped kasdani). These variations allow musicians to choose an instrument that best suits their personal style and the specific demands of their musical tradition. Despite these differences, all Setars share a common lineage and are united by their role as vehicles for melodic and spiritual expression. The diversity of Setar types reflects the instrument’s adaptability and its central place in the musical cultures of Iran and its neighbors.

Characteristics of the Setar

The Setar is distinguished by a number of unique characteristics that set it apart from other stringed instruments. Its sound is soft, intimate, and highly expressive, capable of conveying a wide range of emotions with subtlety and nuance. The instrument’s relatively quiet volume makes it ideal for solo performances and small gatherings, where its delicate tones can be fully appreciated. The Setar’s movable frets and flexible tuning system allow for the exploration of complex modal structures and microtonal intervals, giving the performer access to the full range of Persian musical expression. The playing technique, which involves plucking the strings with the nail of the right index finger, enables a high degree of control over dynamics, articulation, and ornamentation. This technique, combined with the instrument’s responsive construction, allows for the execution of intricate melodic lines, rapid tremolos, and expressive slides.

The Setar’s association with Sufi mysticism and Persian poetry has imbued it with a spiritual significance that transcends its physical form. It is often regarded as an instrument of the soul, capable of facilitating introspection, meditation, and emotional catharsis. The Setar’s role in Persian classical music is both foundational and transformative, serving as a bridge between tradition and innovation. Its timeless melodies and deep cultural connections continue to captivate audiences and inspire musicians worldwide, making it a cherished symbol of ancient musical traditions. Whether played in the solitude of a Sufi retreat or on the stage of a contemporary concert hall, the Setar remains a testament to the enduring power of music to move, inspire, and unite.

Playing Techniques and Sound Modifications

The setar is renowned for its delicate, intimate sound and the nuanced techniques required to master it. Traditionally, the instrument is played while sitting, with the body of the setar resting on the right thigh and the long, slender neck held in the left hand. The right hand plucks the strings using the nail of the index finger, a method that allows for subtle control over dynamics and articulation. In recent decades, some players have experimented with using a plectrum or even the thumb, but the classic approach remains dominant due to its expressive potential. The left hand manipulates the 24 to 26 movable frets—called parde—allowing for microtonal adjustments essential in Persian classical music. Players can produce a variety of ornamentations, including trills, slides (glissandi), and vibrato, by skillfully pressing and sliding their fingers along the frets. The setar’s four strings, each tuned to specific pitches, can be retuned to accommodate different dastgahs (Persian modal systems), offering a wide palette of tonal colors. The addition of the fourth string, known as the Moshtagh string, expanded the instrument’s range and allowed for more intricate melodic and harmonic possibilities.

Sound modifications are achieved through both right and left hand techniques. By varying the angle and force of the plucking finger, a performer can produce tones ranging from whisper-soft to surprisingly resonant. The left hand’s pressure on the frets can subtly alter pitch, enabling the setar to articulate the nuanced intervals characteristic of Persian music. Advanced players often employ techniques such as rapid alternation between strings, harmonics, and muted plucking to further expand the instrument’s expressive range.

Famous Compositions

The setar holds a central place in the repertoire of Persian classical music, especially in solo improvisations and interpretations of traditional compositions. Many of the most revered pieces for setar are not fixed compositions in the Western sense but are instead frameworks for improvisation within the dastgah system. The radif—a collection of ancient melodic figures and motifs—serves as the foundation for much of the setar’s repertoire. Masters of the instrument interpret and elaborate upon these motifs, creating performances that are both rooted in tradition and highly individual. Some notable works associated with the setar include improvisational performances in the dastgahs of Shur, Homayun, and Segah, as well as tasnifs (lyrical songs) and chaharmezrabs (rhythmic instrumental pieces). Modern composers and performers have also created new works for the setar, blending classical forms with contemporary sensibilities. The instrument’s adaptability has allowed it to feature in experimental and cross-cultural collaborations, expanding its repertoire beyond traditional boundaries.

Most Influential Players

The setar’s history is marked by the contributions of several influential musicians who have shaped its evolution and elevated its status in Persian music. Among the most significant figures is Moshtagh Ali Shah, the mystic credited with adding the fourth string in the 19th century, which greatly enriched the instrument’s sound and versatility. His legacy endures in the continued use of the Moshtagh string by setar players. In the 20th and 21st centuries, masters such as Ahmad Ebadi, Mohammad-Reza Lotfi, and Hossein Alizadeh have been pivotal in popularizing the setar both within Iran and internationally. Ahmad Ebadi is celebrated for his refined technique and expressive interpretations, often regarded as a benchmark for aspiring setar players. Mohammad-Reza Lotfi and Hossein Alizadeh have introduced innovative playing methods and expanded the instrument’s repertoire, blending traditional and modern approaches. Their recordings and performances have inspired a new generation of musicians and contributed to the global recognition of the setar.

Other notable figures include Dariush Tala’i and Jalal Zolfonoun, both of whom have made significant contributions as performers, teachers, and scholars. Their dedication to preserving and advancing the art of setar playing has ensured the instrument’s continued relevance and vitality in contemporary Persian music.

Historical Performances or Concerts

Throughout its history, the setar has been featured in both intimate gatherings and public concerts, reflecting its dual role as a spiritual and artistic instrument. In the past, the setar was most commonly played in private settings, such as Sufi gatherings and khaneqahs (dervish lodges), where its gentle, introspective sound was believed to facilitate spiritual contemplation and transcendence. With the rise of concert culture in Iran during the 20th century, the setar began to appear on larger stages, often alongside other traditional instruments. Landmark performances by masters like Ahmad Ebadi and Mohammad-Reza Lotfi introduced broader audiences to the setar’s expressive capabilities. In recent decades, international festivals and world music events have featured setar virtuosos, helping to spread appreciation for the instrument beyond Iran’s borders. Recordings of live performances, particularly those by Hossein Alizadeh and Jalal Zolfonoun, have become reference points for students and enthusiasts. These concerts often showcase the setar’s role in ensemble settings, as well as its capacity for solo improvisation, highlighting the instrument’s versatility and depth.

Maintenance and Care

Proper maintenance is essential to preserve the delicate structure and sound quality of the setar. The instrument is typically crafted from fine woods such as mulberry for the body and walnut for the neck, materials chosen for their acoustic properties and durability. The strings, originally made from animal gut but now commonly metal or nylon, require regular inspection and replacement to ensure optimal tone and playability. Setar owners must protect the instrument from extreme temperatures and humidity, which can cause the wood to warp or crack. It is advisable to store the setar in a hard case when not in use, shielding it from dust and physical damage. Periodic cleaning with a soft, dry cloth helps maintain the finish and prevents buildup on the strings and frets. Frets, which are tied and movable, may need occasional adjustment or replacement to maintain accurate intonation. Players should also monitor the tuning pegs and lubricate them if necessary to ensure smooth operation. Attention to these details not only prolongs the life of the setar but also preserves its distinctive, nuanced sound.

Interesting Facts and Cultural Significance

The setar is steeped in symbolism and cultural meaning within Iranian society. Its name, meaning “three strings,” reflects its original design, but the addition of the fourth string is a testament to the instrument’s capacity for innovation and adaptation. The setar is closely associated with Sufi mysticism, where its introspective sound is believed to facilitate spiritual elevation and self-discovery. Many Sufi poets and musicians have praised the setar for its ability to convey the deepest emotions and connect the listener to the divine. Despite its modest appearance, the setar is regarded as the supreme instrument of Persian classical music, prized for its ability to express subtle shades of feeling and thought. It is often said that the setar “speaks to the soul” of both player and listener, a quality that has made it a favorite among poets, mystics, and musicians alike.

The instrument’s role in Persian culture extends beyond music; it is a symbol of artistic refinement and spiritual depth. Setar players are often revered not only for their technical skill but also for their sensitivity and insight. The instrument’s sound is described as soft, ethereal, and deeply moving, qualities that have inspired countless works of poetry and literature. In recent years, the setar has found new audiences through collaborations with musicians from other traditions, as well as through the efforts of educators and performers who have introduced it to students around the world. Its enduring appeal lies in its unique blend of simplicity and complexity, tradition and innovation—a reflection of the rich cultural heritage from which it springs.

Cultural Significance and Legacy

The setar’s legacy is woven into the fabric of Iranian identity. It is not merely an instrument but a vessel for transmitting the values, stories, and spiritual insights of Persian civilization. Its presence in both sacred and secular contexts underscores its versatility and enduring relevance. In contemporary Iran, the setar continues to inspire new generations of musicians, scholars, and listeners. Its music is heard in concert halls, homes, and spiritual gatherings, a testament to its timeless appeal. The instrument’s influence can also be seen in the development of other Persian stringed instruments, such as the tar, which shares many structural and musical features.

The setar’s journey from the intimate circles of Sufi mystics to the global stage mirrors the broader trajectory of Persian culture—rooted in tradition yet open to change and innovation. As a symbol of introspection, artistry, and spiritual aspiration, the setar remains a cherished and vital part of Iran’s musical and cultural heritage.

FAQ

What is the history of the Setar?

The Setar originated in Persia and dates back to at least the 9th century. It evolved from earlier tanbur-like instruments and gained popularity during the Safavid period. Sufi mystics favored it for its intimate sound. Today, it is a key instrument in classical Persian music.

What materials are used in making a Setar?

The body of the Setar is usually made from mulberry wood, while the neck is crafted from walnut. The strings are typically made from steel or brass. The frets are tied gut or nylon, allowing microtonal adjustments. A wooden plectrum is traditionally used to pluck the strings.

What are the features and sound characteristics of the Setar?

The Setar has a soft, warm, and melodic tone ideal for solo performance. It has four strings, despite its name meaning “three strings.” The instrument allows subtle dynamic expression and rich ornamentation. Its sound is well-suited to Persian modal systems (Dastgah).

Links

Links

References

Other Instrument

Categories