Vihuela

Plucked Instruments

Europe

Between 1001 and 1900 AD

Video

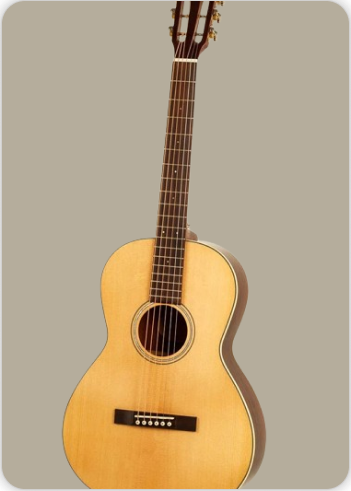

The vihuela is a plucked string instrument that originated in Spain during the Renaissance period. Its appearance is reminiscent of the modern classical guitar, featuring a figure-eight body shape, but it is closely related to the lute in terms of tuning and musical function. The instrument typically has six double courses of gut strings, though some variants have five or even seven courses. Its body is constructed from wood, with a flat back and a fretted neck, giving it a refined and elegant look. The sound of the vihuela is warm and resonant, capable of both delicate polyphony and expressive solo passages. The instrument was designed for fingerstyle playing, allowing for intricate melodies and harmonies, and was often used to accompany the voice or perform complex instrumental music.

Type of Instrument: The vihuela belongs to the family of chordophones, specifically classified as a plucked string instrument. It is a composite chordophone, meaning its sound is produced by the vibration of strings stretched over a resonating body. The vihuela is most closely related to the lute and the guitar, sharing characteristics with both but maintaining a unique identity. It is played by plucking the strings with the fingers, though some historical variants were played with a plectrum or even with a bow. The main types of vihuela include the vihuela de mano (plucked with the fingers), vihuela de penola (plucked with a plectrum), and vihuela de arco (played with a bow). The instrument’s classification reflects its dual heritage, bridging the gap between the medieval lute and the modern guitar.

History of the Vihuela

The vihuela emerged in the mid-15th century in the Kingdom of Aragón, located in northeastern Spain. Its invention marked a pivotal moment in the evolution of stringed instruments in Europe. The vihuela was developed as an aristocratic alternative to the guitar, which was associated with the lower classes. The instrument quickly gained popularity among the Spanish nobility and intellectuals, becoming a symbol of refined taste and cultural sophistication. The vihuela’s influence extended beyond Spain, reaching Portugal and Italy, where it was known by various names such as “viola de mano” in Italian and “viola de mão” in Portuguese. The instrument’s popularity peaked during the 16th century, a period when Spain was a dominant global power, and its music reflected the humanist ideals of the Renaissance. The vihuela was not confined to royal courts; it was embraced by the urban middle class and could be heard in homes, marketplaces, and public gatherings.

During the late 15th and early 16th centuries, the vihuela repertoire flourished, with composers creating complex polyphonic works and arrangements of vocal music. Notable vihuelistas such as Luys Milán, Luys de Narváez, and Alonso Mudarra contributed significantly to its literature, publishing influential collections that showcased the instrument’s expressive range. By the early 17th century, the vihuela began to decline in popularity, gradually supplanted by the baroque guitar. The transition was marked by a shift in musical tastes and the rise of simpler, more accessible instruments. Despite its decline, the vihuela’s legacy endured, influencing the development of later stringed instruments in Spain and the Americas.

Construction and Physical Structure

The construction of the vihuela reflects the craftsmanship and aesthetic sensibilities of Renaissance Spain. The instrument’s body is typically made from carefully selected woods such as spruce or cedar for the soundboard, and maple or rosewood for the back and sides. The body is shaped in a figure-eight form, similar to the modern guitar, but with a flat back and a relatively shallow depth. The soundboard often features intricate decorative elements, including rosettes and inlays, highlighting the instrument’s status as a work of art as well as a musical tool. The neck of the vihuela is fitted with movable gut frets, allowing for precise intonation and flexibility in tuning. The fingerboard is usually made from hardwood, providing durability and a smooth playing surface. The pegbox, located at the end of the neck, holds the tuning pegs, which are used to adjust the tension of the gut strings.

The vihuela typically has six double courses of strings, though some historical examples feature five or seven courses. Each course consists of two strings tuned in unison or octaves, producing a rich and full sound. The strings are anchored at the bridge, which is glued to the soundboard, and stretched over a nut at the top of the fingerboard. The instrument is tuned in fourths with a major third in the middle, mirroring the tuning of the Renaissance lute. The instrument’s size varies, but it is generally smaller and lighter than the modern classical guitar, making it comfortable to hold and play. The combination of fine materials, skilled craftsmanship, and thoughtful design gives the vihuela its distinctive appearance and tonal qualities.

Types of Vihuela

Several distinct types of vihuela developed during its history, each with specific playing techniques and musical functions:

Vihuela de mano: This is the most common type, played with the fingers in a fingerstyle technique. It was used for solo music, accompaniment, and ensemble playing.

Vihuela de penola: This variant was played with a plectrum, producing a brighter and more percussive sound. It was less common but used for certain types of music.

Vihuela de arco: This bowed version of the vihuela served as a precursor to the viola da gamba family. It was played with a bow, allowing for sustained notes and expressive phrasing.

Each type of vihuela contributed to the instrument’s versatility and adaptability, enabling it to perform a wide range of musical styles. The vihuela de mano, in particular, became the standard for solo and ensemble performance, thanks to its expressive capabilities and rich repertoire.

Characteristics of the Vihuela

The vihuela is distinguished by several key characteristics that set it apart from other stringed instruments of its time. Its tuning, identical to the Renaissance lute, allows for the performance of complex polyphonic music and intricate counterpoint. The use of double courses of gut strings gives the instrument a full, resonant sound that blends well with voices and other instruments. The vihuela’s repertoire is notable for its sophistication and diversity, encompassing fantasias, variations, dances, and vocal accompaniments. The instrument’s music is written in tablature, a notation system that indicates finger positions rather than pitches, making it accessible to both amateur and professional musicians. The vihuela’s construction, with its flat back, light body, and movable frets, provides a comfortable playing experience and facilitates rapid changes in position. The instrument’s decorative elements, such as carved rosettes and inlaid purfling, reflect the artistic tastes of Renaissance Spain and underscore its status as a symbol of cultural refinement.

The vihuela’s social significance is also noteworthy. It was embraced by a broad spectrum of society, from aristocrats and intellectuals to merchants and artisans. The instrument played a central role in the musical life of Renaissance Spain, serving as a vehicle for personal expression, artistic contemplation, and social interaction.

The Vihuela in Context

The vihuela’s emergence and popularity coincided with a period of profound cultural and artistic transformation in Spain. The Renaissance brought new ideals of humanism, individual expression, and artistic innovation, all of which found expression in the music of the vihuela. The instrument became a medium for exploring the complexities of polyphonic music, as well as a means of personal and spiritual reflection. The vihuela’s music often drew on vocal models, with composers adapting chansons, motets, and masses for the instrument. This practice not only enriched the vihuela’s repertoire but also contributed to the development of instrumental music as an independent art form. The instrument’s ability to convey both intricate counterpoint and expressive melodies made it a favorite among composers and performers alike. The vihuela’s decline in the early 17th century was part of a broader shift in musical tastes and practices. The rise of the baroque guitar, with its simpler tuning and more accessible playing technique, reflected changing social and artistic priorities. Nevertheless, the vihuela’s legacy persisted, influencing the development of later stringed instruments in Spain and the Americas, including the tiple and the charango.

Legacy and Modern Revival

Although the vihuela fell into obscurity after the 17th century, its music and influence have experienced a revival in recent decades. Musicologists and performers have rediscovered the instrument’s rich repertoire, leading to renewed interest in its construction, technique, and historical context. Modern luthiers have begun building replicas of historical vihuelas, allowing musicians to explore the instrument’s unique sound and expressive possibilities. The vihuela’s legacy is also evident in the music of Latin America, where its influence can be heard in instruments such as the Mexican vihuela, the tiple, and the charango. While these instruments differ in construction and tuning, they share a common heritage rooted in the Spanish vihuela. Contemporary performers and scholars continue to explore the vihuela’s music, bringing new insights into the cultural and artistic life of Renaissance Spain. The instrument’s enduring appeal lies in its ability to bridge the worlds of art and craft, tradition and innovation, and personal expression and communal experience.

Playing Techniques and Sound Modifications

The vihuela is played primarily by plucking or strumming, with techniques varying depending on the type and historical context. The most common form, the vihuela de mano, is played with the fingers, allowing for intricate polyphonic textures and expressive nuances characteristic of Renaissance music. Players employ fingerstyle techniques similar to those used on the lute, with the thumb and fingers articulating independent melodic and harmonic lines. This approach enables the execution of complex contrapuntal music, a hallmark of the vihuela’s repertoire. Another variant, the vihuela de penola, is played with a plectrum, which produces a brighter and more percussive sound. The use of a plectrum allows for rapid strumming and clear articulation of rhythmic passages, making it suitable for dance music and lively accompaniments. For the bowed version, the vihuela de arco, the technique involves drawing a bow across the strings, producing sustained tones and allowing for expressive phrasing akin to that of the viola da gamba.

Sound modifications on the vihuela are achieved through several means. The choice of strings—gut in the Renaissance period, synthetic or nylon in modern reconstructions—affects the instrument’s timbre. The tension and gauge of the strings, as well as their tuning, can be adjusted to produce either a softer, more mellow sound or a brighter, punchier tone. The placement of the right hand, whether closer to the bridge or the fingerboard, also alters the quality of the sound, with bridge proximity yielding a sharper attack and fingerboard proximity resulting in a warmer tone.

Strumming, or “mánico,” is a distinct technique in the Mexican vihuela tradition, where all fingernail tips are used to create a rich, full sound. Some performers grow their fingernails longer to enhance clarity and projection. The use of a finger pick, or “púa,” on the index finger can further brighten the sound. The optimal strumming area is between the sound hole and the neck-body joint, maximizing resonance and tonal clarity.

Famous Compositions

The vihuela boasts a significant body of music from the Spanish Renaissance, with several landmark compositions that have defined its legacy. Among the most influential works are Luis de Narváez’s “Los seys libros del Delphin” (1538), which is the earliest known collection of vihuela music. This monumental work includes fantasias, variations, and intabulations of vocal pieces, showcasing the instrument’s capacity for both original composition and adaptation of vocal polyphony.

Another cornerstone is “Libro de música de vihuela” by Diego Pisador (1552), which contains a wealth of sacred and secular music, including intabulations of motets and chansons by prominent composers of the era. The collection demonstrates the vihuela’s versatility in rendering complex vocal music on a plucked string instrument.

Alonso Mudarra’s “Tres libros de música en cifra para vihuela” (1546) is also seminal, featuring fantasias, tientos, and transcriptions of vocal works. Mudarra’s compositions are notable for their inventive use of harmony and counterpoint, as well as for introducing the earliest known music written specifically for the guitar.

Enríquez de Valderrábano’s “Silva de Sirenas” (1547) and Esteban Daza’s “El Parnaso” (1576) further enrich the vihuela repertoire, offering a range of instrumental genres and styles. These works not only highlight the instrument’s prominence in Renaissance Spain but also provide a window into the musical tastes and practices of the period.

Most Influential Players

The history of the vihuela is closely tied to a select group of virtuoso composers and performers who elevated the instrument to its artistic zenith. Luis de Narváez stands out as one of the earliest and most influential vihuelists, renowned for his technical prowess and innovative compositions. His music set a high standard for subsequent generations and remains central to the vihuela canon.

Alonso Mudarra is another towering figure, whose inventive approach to composition and performance expanded the expressive possibilities of the instrument. His works are frequently performed by modern early music specialists and continue to inspire vihuela players worldwide.

Diego Pisador, though perhaps less celebrated in his lifetime, made significant contributions through his comprehensive collection of vihuela music. His meticulous intabulations and original pieces reflect a deep understanding of both vocal and instrumental traditions.

Enríquez de Valderrábano and Esteban Daza also left an indelible mark, each contributing substantial collections that showcase the vihuela’s adaptability and expressive range. These musicians were not only performers but also teachers and theorists, shaping the pedagogical and artistic landscape of their time.

In the modern era, performers such as Hopkinson Smith and José Miguel Moreno have played a crucial role in reviving the vihuela, bringing its repertoire to contemporary audiences through recordings and concerts. Their scholarship and artistry have ensured that the vihuela’s legacy endures in the realm of early music performance.

Historical Performances or Concerts

During the Renaissance, the vihuela was primarily an instrument of the Spanish and Portuguese aristocracy, often performed in private salons, courts, and chapels. Its music was closely associated with refined social gatherings and intellectual circles, where the appreciation of polyphonic music was a mark of cultural sophistication. Vihuela performances frequently accompanied vocalists, either in solo recitals or as part of small ensembles. The instrument’s ability to render complex polyphonic textures made it ideal for performing intabulations of sacred and secular vocal music, allowing instrumentalists to participate in the rich musical life of the period even in the absence of singers. While there are few detailed records of specific historical concerts, it is known that vihuela music was an integral part of courtly entertainment and religious ceremonies. Manuscripts and printed collections from the 16th century attest to the instrument’s widespread use among the educated elite.

In modern times, historical performances of vihuela music have become a staple of early music festivals and concert series. Notable events include recitals by leading vihuelists at international gatherings such as the Boston Early Music Festival, the Utrecht Early Music Festival, and the Festival Internacional de Música Antigua de Daroca in Spain. These performances, often on meticulously crafted replicas of Renaissance vihuelas, aim to recreate the sound world of the Spanish Golden Age and introduce contemporary audiences to its rich musical heritage.

Maintenance and Care

Proper maintenance and care are essential to preserving the delicate structure and sound quality of the vihuela. Historically, vihuelas were constructed from fine woods such as spruce, maple, and mahogany, with gut strings that required regular replacement due to their susceptibility to humidity and wear. Modern vihuelas, whether used for early music performance or as part of Mariachi ensembles, often employ synthetic or nylon strings, which are more durable and stable. Regular string changes are necessary to maintain optimal tone and playability. It is important to monitor string tension and replace any worn or frayed strings promptly to prevent damage to the instrument. The wooden body of the vihuela should be kept clean and free from dust and moisture. A soft, dry cloth can be used to wipe the surface after each use. The instrument should be stored in a protective case when not in use, away from direct sunlight and extreme temperature fluctuations, which can cause warping or cracking.

The tuning pegs, whether traditional wooden or modern mechanical, should be checked regularly for smooth operation. Lubricating the pegs with a small amount of peg compound can help prevent sticking or slipping. Frets, often made of tied gut or nylon, may need periodic adjustment or replacement to ensure accurate intonation and comfortable playability. For historical instruments or high-quality replicas, consultation with a luthier experienced in early stringed instruments is recommended for any repairs or restoration work. Proper humidity control, ideally between 40% and 60%, will help prevent the wood from drying out or swelling, preserving the instrument’s structural integrity and sound quality.

Interesting Facts and Cultural Significance

The vihuela occupies a unique place in the history of Western music, bridging the gap between the medieval lute and the modern guitar. Its development in 15th-century Spain was partly a response to the popularity of the lute in Italy and northern Europe, with Spanish musicians seeking an instrument that reflected their own cultural identity. One of the most intriguing aspects of the vihuela is its role in the evolution of stringed instruments. The bowed vihuela de arco was a direct precursor to the viola da gamba family, which would become central to Baroque chamber music. The fretted fingerboard of the vihuela made it easier to play in tune compared to earlier bowed instruments, contributing to its popularity among both amateur and professional musicians. The vihuela’s influence extends beyond Spain. Its descendants include the Portuguese violas campaniças and the Latin American tiple and charango, instruments that continue to play vital roles in regional music traditions. In Mexico, the vihuela has been adapted into the Mariachi ensemble, where its distinctive convex back and high-pitched sound provide rhythmic drive and harmonic support.

Culturally, the vihuela was associated with the educated elite of Renaissance Spain, symbolizing refinement and intellectual accomplishment. The instrument’s repertoire, rich in polyphonic complexity, reflects the humanist ideals of the period, where music was seen as a means of personal and spiritual enrichment. The vihuela also played a role in the transmission of musical ideas across Europe and the Americas. Its music, preserved in printed books and manuscripts, influenced the development of guitar music and contributed to the spread of polyphonic techniques. The instrument’s adaptability—whether played with fingers, plectrum, or bow—demonstrates the fluid boundaries between different musical traditions and the ongoing evolution of stringed instruments.

Today, the vihuela enjoys a revival among early music enthusiasts and scholars, who value its historical significance and unique sound. Modern performers and instrument makers continue to explore its possibilities, ensuring that the legacy of the vihuela remains vibrant and relevant in the 21st century. Its music, once the preserve of Renaissance courts, now resonates in concert halls and recordings around the world, connecting contemporary listeners with a rich and fascinating chapter of musical history.

FAQ

What materials were traditionally used to construct the Spanish Vihuela?

The Spanish Vihuela was typically made from high-quality woods such as spruce for the soundboard and rosewood or maple for the back and sides. Gut strings were used for a warm tone. The craftsmanship emphasized resonance and visual elegance.

What are the main types of Vihuela that existed during the Renaissance?

There were mainly two types of Vihuela: the vihuela de mano (played with fingers) and vihuela de arco (bowed). The vihuela de mano is the most commonly known and resembles the lute in tuning and style.

What was the role of the Vihuela in Spanish Renaissance music?

The Vihuela played a central role in Spanish Renaissance court and art music. It was used for solo performances, accompaniment, and complex polyphonic compositions, often preferred over the lute in Spain during the 15th and 16th centuries.

Links

Links

References

- Vihuela - Wikipedia

- Vihuela | Spanish, Renaissance, Guitar-like | Britannica

- The Vihuela - A Mariachi Instrument Overview | West Music

- What is a Vihuela? Learn About This Spanish String Instrument | Skillshare Blog

- Spanish Vihuela — Gamut Music. Inc.

- Vihuela Music of the Spanish Renaissance | Warner Classics

Other Instrument

Categories