Yangqin

Plucked Instruments

Asia

Between 1001 and 1900 AD

Video

The yangqin is a trapezoidal hammered dulcimer, a stringed musical instrument that is played by striking its strings with lightweight bamboo beaters. Its name in Chinese, 扬琴 (yángqín), translates to “acclaimed zither,” though it was historically known as 洋琴, meaning “foreign zither.” The instrument produces a bright, resonant, and often shimmering sound, with a timbre that is both percussive and melodic. The yangqin is a central feature in various Chinese musical ensembles, including folk, classical, and opera orchestras, and is also played as a solo instrument. Its versatility allows it to perform both melodic lines and harmonic accompaniment, making it a vital contributor to the texture of Chinese music.

Type of Instrument: The yangqin belongs to the family of hammered dulcimers, which are classified as chordophones—stringed instruments in which the sound is produced by the vibration of stretched strings. More specifically, the yangqin is a struck zither, as its strings are not plucked or bowed but rather struck with hammers. In the traditional Chinese instrumental classification system, it was originally categorized as a “silk” instrument due to its early use of silk strings, but modern versions use metal strings, which have altered its classification and sound profile.

History of the Yangqin

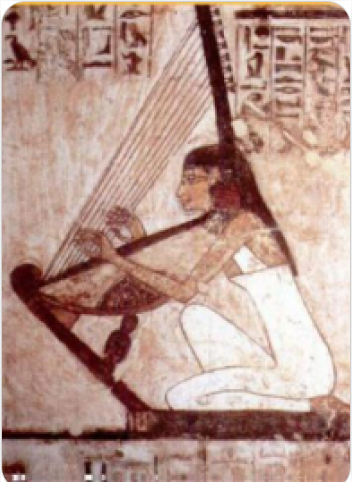

The origins of the yangqin are complex and reflect centuries of cultural exchange. The instrument is believed to have been introduced to China in the 17th century, during the late Ming or early Qing dynasty. Its antecedents can be traced to the hammered dulcimers of Persia (Iran), particularly the santur, and to European dulcimers, which themselves have ancient roots in the psaltery of the Middle East and Europe. Theories about its introduction to China vary: some suggest it came overland via the Silk Road from Central Asia, while others propose it arrived by sea through the port of Guangzhou (Canton). There is also a theory that the Chinese developed it independently, though the similarities with the santur and European dulcimers are striking. Once in China, the yangqin was quickly assimilated into folk music traditions and became a staple of local ensembles. Initially, it was most popular among the civilian class, and its use in palace music was limited. As folk music gained prominence at the end of the 17th century, the yangqin found its way into various regional music styles, including Cantonese music, Jiangnan sizhu (Silk and Bamboo music from the Shanghai region), Sichuan music, and the music of northeast China. Over time, it developed its own repertoire and performance techniques, becoming an integral part of Chinese musical culture.

Globally, the yangqin is part of a broader family of hammered dulcimers, which are found in many cultures under different names: the santur in Iran and India, the cimbalom in Hungary, the dulcimer in Western Europe and North America, the hackbrett in German-speaking countries, and the khim in Thailand and Cambodia. Each of these instruments has evolved unique features and playing styles, reflecting local musical traditions and innovations.

Construction and Physical Structure

The yangqin is characterized by its distinctive trapezoidal shape, with the longer side facing the player. The soundboard is typically made of thin, resonant wood, often spruce or fir, which helps amplify the sound of the vibrating strings. The instrument is supported by a wooden frame and often rests on a stand or table during performance. Modern yangqin instruments usually have 144 strings, grouped into courses of up to five strings each. Each course is tuned to the same pitch, which increases the instrument’s volume and resonance. The strings vary in thickness, with thicker strings producing lower pitches and thinner strings producing higher ones. The strings are anchored at one end by tuning pins and at the other by hitch pins or screws, which are often concealed beneath a hinged panel that can be opened for tuning.

The yangqin features four to five bridges, which are long, narrow strips of wood with protruding stubs that support the strings. These bridges are arranged in a way that allows for a wide range of pitches and chromatic possibilities. From right to left, the bridges are typically referred to as the bass bridge, right bridge, tenor bridge, left bridge, and chromatic bridge. The arrangement of the strings and bridges enables the performer to access a broad range of notes by striking the strings on different sides of the bridges. The instrument is played with two lightweight bamboo beaters, also known as hammers or mallets. These beaters may have rubber or felt tips to produce different tonal qualities. Professional yangqin players often carry several sets of beaters, each designed to elicit a specific sound from the instrument, much like a percussionist’s selection of drumsticks.

Types of Yangqin

The yangqin has evolved into several types, both within China and internationally, reflecting regional preferences and musical requirements. In China, the most common types are distinguished by their size, range, and the number of bridges:

Traditional Yangqin: These instruments typically have three or more courses of bridges and were historically strung with silk or bronze strings. They produce a softer, mellower sound and are still used in some traditional ensembles, such as those performing Jiangnan sizhu or Cantonese music.

Modern Yangqin: Since the 1950s, modern yangqin have been constructed with steel alloy strings, sometimes with copper winding for the bass notes. These instruments are larger, with up to five courses of bridges, and are often tuned chromatically to accommodate a wider range of music, including Western compositions and contemporary Chinese works.

Regional Variants: Within China, regional styles of yangqin playing have led to subtle differences in instrument construction and tuning. For example, the Guangdong yangqin, Jiangnan Sizhu yangqin, Sichuan yangqin, and northeast yangqin each have unique characteristics suited to their respective musical traditions.

International Relatives: The yangqin’s relatives include the Iranian santur, the Indian santoor, the Thai and Cambodian khim, the Hungarian cimbalom, and the European and American dulcimer. Each of these instruments has adapted the basic hammered dulcimer design to local musical needs, resulting in variations in size, number of strings, tuning systems, and playing techniques.

Characteristics of the Yangqin

The yangqin is renowned for its bright, clear, and penetrating sound, which can cut through the texture of an ensemble or provide a shimmering solo voice. The use of metal strings and lightweight hammers allows for rapid articulation and dynamic contrasts, making the instrument capable of both lyrical melodies and virtuosic passages. The yangqin’s wide range—often spanning more than four octaves—enables it to perform both bass and treble roles within a group. One of the defining features of the yangqin is its ability to produce both melodic and harmonic content. Unlike many traditional Chinese instruments, which are primarily monophonic, the yangqin can play chords and arpeggios, providing harmonic support in ensembles. This versatility has made it an essential component of Chinese orchestras and chamber groups. The instrument’s construction also allows for a variety of playing techniques. Players can strike the strings with different parts of the beaters, use glissandi (sliding effects), and employ damping techniques to control the resonance and articulation of the notes. Advanced performers may use multiple beaters or employ special effects, such as tremolos and rapid repeated notes, to expand the expressive range of the instrument.

In terms of repertoire, the yangqin has absorbed influences from both Chinese and Western music. Traditional pieces often feature pentatonic or modal melodies, while modern compositions may incorporate chromaticism, complex rhythms, and extended techniques. The instrument is used in a wide range of musical contexts, from solo recitals to large-scale orchestral works, and is frequently featured in Chinese opera, folk music, and contemporary compositions.

Playing Techniques and Sound Modifications

The yangqin is played using a pair of lightweight bamboo hammers, sometimes tipped with rubber or felt to alter the timbre. The basic technique involves striking the strings, which are stretched over a trapezoidal wooden soundbox, to produce clear, bell-like tones. Players use a variety of strokes to achieve different effects. Single-note melodies are articulated with precision, while chords are created by striking multiple strings simultaneously. Rapid passages, trills, and tremolos are common, showcasing the instrument’s agility and expressive range. Players often employ glissando by sliding the hammer across adjacent strings, creating a sweeping, harp-like effect. Muting techniques, where the hand or a finger lightly touches the strings to dampen resonance, are used to create staccato or percussive sounds. Advanced performers may use cross-string techniques, alternating between left and right hands to execute complex, fast-moving passages. The yangqin’s tuning system allows for chromaticism and microtonal adjustments, enabling the performance of both traditional Chinese scales and Western harmonies.

Sound modifications are achieved through several means. The material and shape of the hammers influence the brightness or mellowness of the tone. Adjusting the position where the string is struck—closer to the bridge or towards the center—also changes the timbre. Modern yangqin designs sometimes incorporate additional dampening mechanisms or extended string ranges, broadening the instrument’s expressive palette. In contemporary settings, electronic amplification and effects may be used to further expand its sonic possibilities.

Famous Compositions

The yangqin has inspired a repertoire that spans from traditional Chinese folk music to contemporary concert works. One of the most notable modern compositions is “Rhapsody” by Wang Danhong, performed by Shen Xiangyang with the China National Traditional Orchestra. This piece blends traditional yangqin techniques with jazz-influenced harmonies and rhythms, highlighting the instrument’s adaptability to new musical languages. Traditional pieces often feature the yangqin in ensemble settings, such as in the accompaniment of regional operas or narrative storytelling. In Taiwanese Gezai opera, the yangqin is the principal accompanying instrument, providing melodic and rhythmic support. Other well-known works include arrangements of folk tunes and adaptations of Western classical pieces, such as the “Yellow River Boatmen Song,” famously performed by Yangqin Zhao. These pieces demonstrate the yangqin’s ability to convey both lyrical melodies and vibrant, rhythmic textures.

Contemporary composers continue to write for the yangqin, exploring its potential in solo, chamber, and orchestral contexts. The instrument’s inclusion in fusion projects and world music ensembles has led to new compositions that blend Chinese traditions with global influences, expanding its repertoire and audience.

Most Influential Players

Several musicians have played pivotal roles in the development and popularization of the yangqin.

Yangqin Zhao stands out as one of the foremost soloists, renowned for her technical mastery and innovative approach. She has won national competitions, recorded influential albums, and served as an educator, inspiring a new generation of performers. Her interpretation of the “Yellow River Boatmen Song” is particularly celebrated for its virtuosity and emotional depth.

Shen Xiangyang is another prominent figure, known for his performances with the China National Traditional Orchestra and his role in premiering contemporary works like “Rhapsody.” These artists, along with others such as professors Shengmao Hong and Mingqing Guo, have contributed to the evolution of yangqin performance, expanding its technical possibilities and elevating its status within Chinese and international music circles.

In addition to soloists, many yangqin players have made significant contributions as ensemble musicians, composers, and teachers, ensuring the instrument’s continued vitality and relevance.

Historical Performances or Concerts

The yangqin has featured in numerous significant performances, both in China and abroad. The China National Traditional Orchestra, established in 1960, regularly showcases the yangqin in its concerts, presenting both traditional and contemporary works. These performances often highlight the instrument’s role as the “piano accompaniment” in Chinese orchestras, providing harmonic and rhythmic foundation. Historic concerts, such as national competitions and international tours, have brought the yangqin to wider audiences. Yangqin Zhao’s victory in the first nationwide folk music instrumental competition in 1982 marked a milestone, drawing attention to the instrument’s expressive potential. Her subsequent recordings and live performances have been influential in shaping public perception of the yangqin. In Taiwan and Fujian, the yangqin is central to Gezai opera performances, where it accompanies singers and dancers in both traditional and modern productions. These events serve as important cultural gatherings, preserving and revitalizing regional musical heritage.

Maintenance and Care

Proper maintenance is essential to preserve the yangqin’s sound quality and longevity. The wooden body should be kept in a stable environment, avoiding extremes of humidity and temperature that could cause warping or cracking. Regular dusting and gentle cleaning with a soft cloth help maintain the instrument’s appearance. Strings, typically made of steel, require periodic inspection and replacement if they become worn or corroded. Tuning is a meticulous process, as the yangqin’s many strings must be adjusted to precise pitches. Players use a tuning wrench to turn the pegs, often guided by electronic tuners or tuning forks. The bamboo hammers should be checked for splintering or wear, and replaced as needed to ensure consistent sound production. Bridges must remain properly positioned and free of debris, as their placement affects tuning and resonance. When not in use, the yangqin is best stored in a protective case or covered with a cloth to shield it from dust and accidental damage. Transporting the instrument requires care, as the delicate strings and bridges can be easily displaced. Many musicians use padded cases and secure the bridges before moving the yangqin to prevent shifting during transit.

Interesting Facts and Cultural Significance

The yangqin’s origins trace back to ancient Mesopotamia, where similar hammered string instruments appeared in Sumerian, Babylonian, and Assyrian civilizations. Its journey to China was shaped by cultural exchanges along trade routes, including influences from Greek, Middle Eastern, and European musical traditions. By the end of the Ming Dynasty, the yangqin had become established in China, particularly in coastal regions, before spreading throughout the country. The instrument’s name, meaning “foreign zither,” reflects its cross-cultural heritage. Over centuries, the yangqin was adapted to fit Chinese musical aesthetics, becoming an integral part of folk music, opera, and narrative arts. Its role as an accompaniment instrument in regional operas, such as Taiwanese Gezai opera, underscores its importance in local cultural identity.

The yangqin is often compared to the piano, both in its function within ensembles and its ability to produce rich harmonies. Its versatility allows it to bridge traditional and modern genres, making it a favorite in contemporary fusion projects. The instrument’s distinctive sound—simultaneously melodic and percussive—has made it a symbol of Chinese musical innovation. In modern times, the yangqin is featured in music education programs, and digital versions, such as VST plugins, have introduced its sound to global audiences. These technological advancements enable composers and producers to incorporate yangqin timbres into a wide range of musical styles, from film scores to electronic music.

The yangqin’s enduring appeal lies in its blend of historical depth, technical versatility, and cultural resonance. It serves as a testament to the power of musical exchange and adaptation, continuing to inspire musicians and listeners around the world.

FAQ

What is the construction and material used in the Yangqin?

The Yangqin is a Chinese hammered dulcimer with a trapezoidal wooden soundboard. It uses metal strings—usually steel and copper-wound—and is played with bamboo mallets. The bridges are made of hardwood and fine-tune the pitch. The frame is typically crafted from paulownia or other resonant woods.

What are the different types of Yangqin used today?

Modern Yangqin types include the 402, 601, and 802 models, distinguished by the number of bridges and string groupings. Each type offers varying pitch ranges and tonal qualities. The 402 is more traditional, while the 802 is commonly used in orchestras for its extended range and dynamic capacity.

What is the role of the Yangqin in Chinese music?

The Yangqin is used in traditional Chinese ensembles, opera, solo performances, and modern orchestras. It bridges harmony and rhythm in musical compositions. Its bright, percussive sound makes it versatile across classical, folk, and even fusion genres in China and beyond.

Links

Links

References

Other Instrument

Categories