Tanbur

Plucked Instruments

Middle East

Between 1001 and 1900 AD

Video

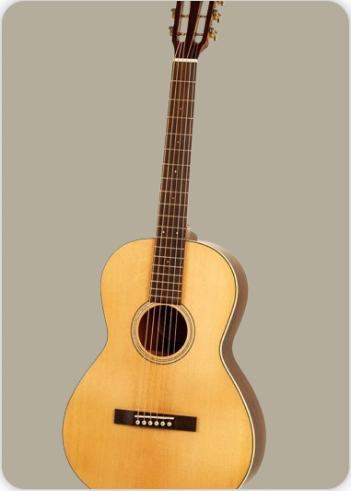

The Tanbur, sometimes spelled tambur or tanboor, is a long-necked, fretted string instrument that holds a prominent place in Turkish classical and traditional music. Known for its graceful structure and resonant, haunting sound, the Tanbur is recognized as one of the oldest and most important musical instruments in Turkey. Its design features a hemispherical or pear-shaped wooden body and a long, slender neck adorned with numerous frets. The instrument is typically played with a plectrum, known as a mizrap, which is often made from tortoiseshell or similar materials. The Tanbur’s unique sound is characterized by its ability to produce microtonal intervals, a hallmark of Turkish music, allowing musicians to explore intricate melodic expressions and emotional depth. Whether performed solo or as part of an ensemble, the Tanbur’s melodies are deeply evocative, transporting listeners to the heart of Turkish musical heritage.

Type of Instrument: The Tanbur is classified as a string instrument, specifically a long-necked lute. It is a member of the chordophone family, which encompasses instruments that produce sound through vibrating strings stretched between two points. Within the context of Turkish music, the Tanbur is distinguished by its elongated neck and fretted fingerboard, setting it apart from other lutes and string instruments. There are two main variants of the Tanbur: the plucked Tanbur (mızraplı tanbur), which is played with a plectrum, and the bowed Tanbur (yaylı tanbur), which is played with a bow. The plucked version is more commonly associated with classical Turkish music, while the bowed Tanbur is appreciated for its sustained, expressive tones. Both types are integral to the performance of traditional and courtly music, and the musicians who play them are referred to as tanburi.

History of the Tanbur

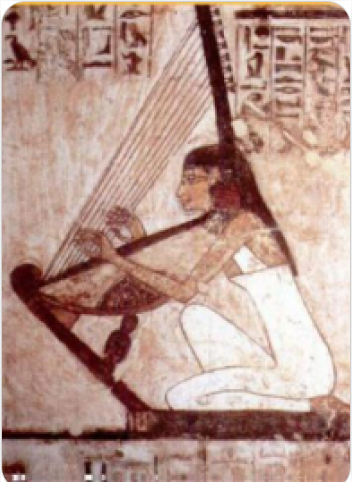

The origins of the Tanbur can be traced back through centuries of musical evolution across Asia and the Middle East. The instrument’s name is believed to derive from the Arabic word “tunbur,” and it shares etymological roots with a wide array of similarly named instruments found throughout Persia, Central Asia, and even ancient Mesopotamia. Some scholars suggest that the Tanbur descended from the kopuz, an ancient string instrument still played among Turkic peoples of Central Asia and the Caspian region. The Sumerian “pantur” is also cited as a possible ancestor, highlighting the instrument’s deep historical lineage. By the 15th century, the Tanbur had begun to assume a form recognizable today, with descriptions from the late medieval period likening it to a large spoon with three strings. Over time, the instrument evolved further, particularly during the Ottoman era. By the 17th century, the Tanbur had become a central feature of the Ottoman court’s musical ensembles, celebrated for its refined sound and capacity for expressive nuance. Paintings from the 18th century depict the instrument with multiple strings and courses, indicating its continued development.

Throughout its history, the Tanbur has played a vital role in both classical and folk traditions. In the royal courts of the Ottoman Empire, it was a symbol of sophistication and artistic achievement, often performed alongside other esteemed instruments such as the ney (reed flute) and ud (short-necked lute). In rural and urban settings alike, the Tanbur contributed to the communal fabric of Turkish music, enriching folk melodies and dances with its distinctive timbre. Today, the Tanbur remains a cherished symbol of Turkey’s musical heritage, its legacy preserved by dedicated musicians and craftsmen who continue to build and play the instrument using traditional methods.

Construction and Physical Structure

The Tanbur is renowned for its intricate construction, which combines artistry and acoustic precision. The instrument is made almost entirely of wood, with each component carefully selected and crafted to enhance its tonal qualities. The body, or “tekne,” is typically assembled from strips of hardwood known as ribs, which are joined edge to edge to form a semi-spherical or pear-shaped shell. The number of ribs can vary, with traditional instruments often featuring 17, 21, or 23 ribs, though some older examples may have as few as 7 or as many as 23. Common woods used for the ribs include mahogany, flame maple, Persian walnut, mulberry, and juniper, among others. Decorative strips called “fileto” are sometimes inserted between the ribs for ornamental purposes. The soundboard, or “göğüs,” is a thin, circular plate made from resonant woods such as spruce, fir, or cedar. This plate, usually 2.5 to 3 millimeters thick and measuring 30 to 35 centimeters in diameter, is mounted on the body with simmering glue and encircled by a wooden ring. Unlike many Western string instruments, the Tanbur often lacks a prominent soundhole, or features only a very small, unornamented opening, which contributes to its unique sonority.

The neck, or “sap,” is long and slender, typically measuring 100 to 110 centimeters in length and about 4 to 4.5 centimeters in diameter. The fingerboard is fitted with up to 48 gut or silk-thread frets, which are meticulously placed to accommodate the microtonal intervals of Turkish music. These frets are fixed to the neck using tiny nails and can be adjusted to fine-tune the instrument’s intonation. The instrument’s bridge is trapezoidal and mobile, allowing for subtle adjustments to the string height and tension. The upper bridge, located between the pegbox and the neck, is traditionally made of bone. The pegs themselves are often crafted from ebony, prized for its durability and smooth action. The Tanbur is strung with six to nine strings, typically arranged in courses. Historically, the instrument had as many as eight strings, but modern versions usually feature seven. The strings are made from metal or gut, and only the lowest course is pressed against the frets during performance, while the upper courses act as sympathetic resonators.

A distinctive feature of the Tanbur is its plectrum, known as “bağa.” Made from tortoiseshell or similar materials, the plectrum is cut in an asymmetrical V-shape and polished at a 45-degree angle on the tip. It measures approximately 2 to 2.5 millimeters thick, 5 to 6 millimeters wide, and 10 to 15 centimeters long. The plectrum’s design allows for precise articulation and dynamic control, essential for the instrument’s expressive playing style.

Types of Tanbur

The Tanbur exists in several distinct forms, each with its own playing technique and musical context. The two primary types are:

Plucked Tanbur (Mızraplı Tanbur): This is the most common form of the instrument, played with a plectrum. It is a staple of Turkish classical music and is valued for its clarity, brightness, and ability to produce rapid, intricate passages. The plucked Tanbur is typically used in solo performances as well as in ensembles, where it often takes a leading melodic role.

Bowed Tanbur (Yaylı Tanbur): The bowed version of the instrument, known as the yaylı tanbur, is played with a bow rather than a plectrum. This variant produces a sustained, lyrical sound, making it particularly well-suited to expressive, slow-tempo pieces. The yaylı tanbur is a relatively recent innovation, but it has gained popularity for its ability to blend seamlessly with other bowed and wind instruments in Turkish art music.

In addition to these main types, there are regional and stylistic variations of the Tanbur, reflecting the diverse musical traditions of Turkey and neighboring regions. Some instruments are designed specifically for folk music, with modifications to the body shape, string arrangement, or fret placement to suit local styles.

Characteristics of the Tanbur

The Tanbur possesses several distinctive characteristics that set it apart from other string instruments, both in terms of sound and playing technique.

Microtonal Capability: One of the most remarkable features of the Tanbur is its ability to produce microtonal intervals, which are essential to the modal systems (makam) of Turkish music. The instrument’s numerous, movable frets allow for precise tuning and the execution of quarter tones and other intervals not found in Western music. This microtonal flexibility enables musicians to explore a vast palette of melodic colors and emotional nuances.

Resonant Sound: The Tanbur’s construction, with its large, hollow body and thin soundboard, gives it a warm, resonant tone that can fill both intimate and large spaces. The sympathetic strings, which are not directly played but vibrate in response to the plucked strings, add depth and richness to the sound, creating a shimmering, ethereal effect.

Expressive Playing Technique: Unlike many fretted instruments, the Tanbur is not typically played by pressing the strings firmly against the frets. Instead, the musician uses a light touch, allowing the strings to vibrate freely and produce subtle variations in pitch and timbre. The use of the mizrap plectrum further enhances the instrument’s expressive range, enabling rapid passages, delicate trills, and dynamic contrasts.

Versatility: While the Tanbur is most closely associated with Turkish classical music, it is also used in folk traditions and contemporary compositions. Its adaptability has allowed it to remain relevant across centuries, bridging genres and generations.

Symbolic Significance: Beyond its musical attributes, the Tanbur is a symbol of cultural identity and artistic refinement in Turkey. It is revered as a vehicle for spiritual expression, particularly in the context of Sufi music, where its melodies are believed to facilitate transcendence and communion with the divine.

The Tanbur in Turkish Music and Culture

The Tanbur’s influence extends far beyond its role as a musical instrument. It is deeply woven into the fabric of Turkish culture, serving as a conduit for artistic expression, historical continuity, and communal identity. In the Ottoman period, the Tanbur was a fixture of courtly life, performed by master musicians in palaces and salons. Its repertoire encompassed both secular and sacred music, reflecting the cosmopolitan nature of the empire. The instrument was also embraced by Sufi mystics, who regarded its sound as a means of spiritual elevation and contemplation. Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the Tanbur continued to evolve, adapting to changing musical tastes and social contexts. It became a staple of urban music scenes, featured in cafes, theaters, and radio broadcasts. Renowned tanburi, or Tanbur players, emerged as cultural icons, celebrated for their virtuosity and innovation.

In contemporary Turkey, the Tanbur remains a vital part of the country’s musical landscape. It is taught in conservatories, performed in concert halls, and cherished by audiences of all ages. Efforts to preserve and promote the instrument have led to a resurgence of interest among young musicians, ensuring that the Tanbur’s legacy will endure for generations to come.

Playing Techniques and Sound Modifications

The Turkish tanbur is renowned for its unique playing technique, which sets it apart from other stringed instruments. Traditionally, the tanbur is played with a plectrum known as a mizrap, often made from tortoiseshell or similar materials. The use of the mizrap allows for a crisp, articulate sound and enables the player to execute rapid, intricate passages with precision. Unlike many other fretted instruments, tanburists do not press the strings directly against the frets. Instead, the player’s fingers lightly touch the strings, allowing for subtle pitch inflections and microtonal variations that are essential in Turkish classical music. This technique is particularly important for navigating the complex makam system, which relies on intervals smaller than those found in Western music. The tanbur’s sound is further enriched by its string configuration. Typically, it has six to nine strings arranged in courses, with only the lowest course being actively fingered while the upper courses resonate sympathetically. This setup creates a rich, layered sound that is both resonant and expressive. Advanced players can manipulate the timbre and dynamics by varying the angle and force of the mizrap, as well as by adjusting their finger pressure on the strings. The instrument’s long neck, often fitted with up to 48 gut or silk-thread frets, allows for an extensive range of pitches and facilitates the execution of intricate melodic lines.

Sound modifications are also achieved through the use of movable frets, which can be adjusted to accommodate the specific intervals required by different makams. This adaptability is crucial for performing the wide array of modes in Turkish music, each with its own distinct character and emotional expression. The tanbur’s construction, with its hemispherical body and thin, resonant soundboard, further contributes to its distinctive, haunting tone.

Famous Compositions

The tanbur has inspired a wealth of compositions, particularly within the realm of Turkish classical music. Many pieces written for the tanbur are instrumental works that showcase the instrument’s expressive capabilities and the intricacies of the makam system. Among the most celebrated are the long-form instrumental pieces known as peşrevs and semais, which often serve as the opening and closing movements in classical suites. One of the most famous compositions associated with the tanbur is the “Tanbur Peşrevi” by Tanburi Cemil Bey, a legendary figure in Ottoman classical music. His works are considered masterpieces, blending technical virtuosity with deep emotional resonance. Other notable compositions include “Nihavend Longa” and “Hicaz Peşrevi,” both of which are staples in the repertoire of tanburists and frequently performed in concerts and recordings. In addition to these classical works, the tanbur has also been featured in contemporary compositions that seek to bridge traditional and modern musical idioms. Its unique sound has made it a favorite among composers looking to evoke the rich cultural heritage of Turkey while exploring new musical territories.

Most Influential Players

Throughout its history, the tanbur has been championed by a number of virtuoso performers who have elevated the instrument to new heights. Among the most influential is Tanburi Cemil Bey, whose innovative playing style and prolific output have left an indelible mark on Turkish music. His recordings, though made in the early 20th century, remain a benchmark for aspiring tanburists. Another towering figure is Tanburi Büyük Osman Bey, renowned for his mastery of both the instrument and the theoretical underpinnings of Turkish music. His interpretations of classical repertoire are still studied and admired today. In more recent times, performers such as Necdet Yaşar have continued the tradition, bringing the tanbur to international audiences and ensuring its continued relevance in the modern era. These musicians are not only celebrated for their technical prowess but also for their deep understanding of the makam system and their ability to convey the emotional depth of Turkish music. Their performances, whether in the intimate setting of a meşk (musical gathering) or on the grand stage of a concert hall, have inspired generations of musicians and listeners alike.

Historical Performances or Concerts

The tanbur has a long history of being featured in significant performances, both in the royal courts of the Ottoman Empire and in public concerts. During the Ottoman period, the tanbur was a central instrument in the court orchestra, accompanying vocalists and other instrumentalists in elaborate musical suites. These performances were often highly formalized, with strict adherence to the conventions of Turkish classical music. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, public concerts featuring the tanbur became increasingly common, particularly in Istanbul. These events provided a platform for virtuoso performers to showcase their skills and for composers to present new works. Notable historical performances include those given by Tanburi Cemil Bey, whose concerts were renowned for their technical brilliance and emotional intensity. In modern times, the tanbur continues to be featured in major music festivals and cultural events, both in Turkey and abroad. Its distinctive sound and rich cultural associations make it a highlight of performances dedicated to Turkish classical and folk music. Recordings of historical concerts, as well as contemporary performances, are widely available and serve as an important resource for both musicians and enthusiasts.

Maintenance and Care

Proper maintenance and care are essential for preserving the tanbur’s delicate sound and ensuring its longevity. The instrument is typically constructed from fine woods such as mulberry, walnut, or mahogany for the body, with a soundboard made from spruce or cedar. These materials are sensitive to changes in temperature and humidity, so it is important to store the tanbur in a stable environment, away from direct sunlight and extreme conditions. Regular cleaning is necessary to prevent the buildup of dust and oils, particularly on the strings and fingerboard. The strings, usually made of steel or bronze, should be wiped down after each use to prevent corrosion. Over time, they will need to be replaced to maintain optimal sound quality. The movable frets, often made of gut or silk thread, require periodic adjustment to ensure accurate intonation. This process should be undertaken with care, as improper handling can damage the delicate neck or disrupt the instrument’s tuning. The bridge and pegs, typically made from ebony or bone, should also be checked regularly for signs of wear or damage.

If the tanbur develops cracks or other structural issues, it is important to consult a skilled luthier who is familiar with the instrument’s unique construction. Routine inspections and professional maintenance will help preserve the tanbur’s sound and playability for generations to come.

Interesting Facts and Cultural Significance

The tanbur occupies a unique place in Turkish culture, serving as both a symbol of artistic expression and a repository of musical tradition. Its origins can be traced back to ancient times, with links to a wide family of long-necked lutes found throughout Central Asia, Persia, and the Middle East. The instrument’s name, derived from the Arabic “tunbur,” reflects this rich and diverse heritage. One of the most fascinating aspects of the tanbur is its role in the development of Turkish classical music. The instrument was a favorite of Ottoman sultans and court musicians, and its sound became synonymous with the refined aesthetic of the imperial court. The tanbur’s ability to produce microtonal intervals made it an ideal vehicle for exploring the subtleties of the makam system, which lies at the heart of Turkish music. The tanbur is also notable for its construction, which combines artistry and craftsmanship. Each instrument is hand-made by master luthiers, with careful attention paid to the selection of woods, the shaping of the body, and the placement of the frets. This meticulous process ensures that each tanbur is unique, with its own distinctive sound and character.

In addition to its classical associations, the tanbur has played an important role in Turkish folk music, where it adds depth and texture to traditional melodies and dances. Its haunting sound has the power to evoke a wide range of emotions, from joy to melancholy, making it a beloved instrument among musicians and audiences alike. The tanbur’s cultural significance extends beyond music. It is often depicted in Turkish art and literature, symbolizing the country’s rich artistic heritage and its enduring connection to the past. The instrument’s continued popularity is a testament to the dedication of musicians and craftsmen who have worked tirelessly to preserve and promote its legacy.

FAQ

What is the historical origin of the Turkish Tanbur?

The Turkish Tanbur originated during the Ottoman Empire and has roots tracing back to Central Asia and Persia. It evolved significantly in Turkey around the 18th century. This long-necked lute became integral to classical Turkish music. It was notably played in Ottoman court music traditions.

What are the main construction materials of the Turkish Tanbur?

The body of the Turkish Tanbur is typically made from mulberry, walnut, or mahogany wood. Its long neck is often crafted from hardwood like beech or maple. The soundboard is traditionally made of thin spruce, enhancing resonance. Metal or nylon strings are stretched across movable frets.

What are the main musical features and uses of the Tanbur in Turkish music?

The Tanbur is known for its deep, resonant tone and microtonal capabilities. It's a key instrument in Turkish classical and Sufi music. Players use a plectrum to articulate intricate melodic phrases. It is often used to perform makam-based compositions and improvisations.

Links

Links

References

Other Instrument

Categories