Bianqing

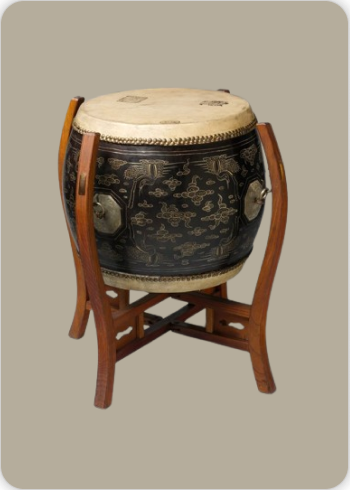

Percussions

Asia

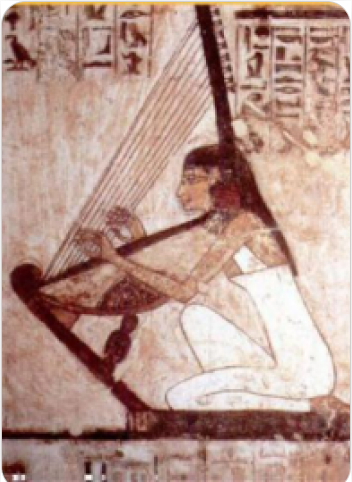

Ancient

Video

The Bianqing is an ancient Chinese musical instrument classified as an idiophone, a type of percussion instrument that produces sound primarily through the vibration of its solid material without the use of strings or membranes. It consists of a set of stone chimes, usually made of jade, marble, or other types of sonorous stone, which are suspended from a wooden frame and struck with a mallet to produce musical tones. The instrument is known for its clear, resonant sound and is often used in traditional Chinese court and religious music.

Bianqing is part of the larger category of Chinese lithophones, which are instruments that generate sound through the striking of stones. Unlike Western percussion instruments like drums, which rely on stretched membranes, or bells, which use hollow metal bodies, Bianqing produces music through the unique properties of carefully shaped stones. The shape, thickness, and composition of each stone determine the specific pitch and tone it produces.

This instrument is usually played in a set, with multiple stones arranged in ascending or descending order of pitch. Each stone is carefully selected and carved to ensure it produces the desired note when struck. Traditional Bianqing sets can contain various numbers of stones, with the most elaborate versions consisting of sixteen or more chimes. It has been a central part of Chinese ceremonial music for thousands of years and remains an important symbol of ancient Chinese musical traditions.

History and Origin

The Bianqing has its origins in China and dates back to the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE). It is one of the oldest known Chinese musical instruments and has played an essential role in both religious and court music throughout Chinese history. The earliest evidence of Bianqing comes from archaeological discoveries, where stone chimes were found in ancient tombs and ceremonial sites. These findings suggest that the instrument was highly valued by Chinese aristocrats and scholars, who used it for both musical and ritualistic purposes.

Development in the Zhou Dynasty

During the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE), the use of Bianqing became more widespread, especially in state rituals and Confucian ceremonies. The instrument was often played in temples and royal courts as part of elaborate musical ensembles. It was regarded as a symbol of refinement and intellectual achievement, aligning with Confucian ideals of harmony and order. Ancient Chinese texts describe the use of Bianqing in court orchestras, where it was played alongside other traditional instruments like the guqin, bells, and flutes.

Evolution in Later Dynasties

The Bianqing continued to be an important instrument throughout the Han (206 BCE–220 CE), Tang (618–907 CE), and Song (960–1279 CE) Dynasties. Each dynasty brought refinements to the instrument’s design and playing techniques. During the Tang Dynasty, for instance, Bianqing was frequently used in Buddhist and Taoist ceremonies, reflecting its growing significance in religious music. The instrument also appeared in international musical exchanges, as China’s influence spread to neighboring countries like Korea and Japan.

During the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1912) Dynasties, Bianqing was incorporated into large imperial orchestras and Confucian ritual music. It remained a prestigious instrument associated with scholarly and religious traditions. Even as Western musical influences entered China in the 19th and 20th centuries, Bianqing continued to be used in traditional performances and remains a respected part of Chinese cultural heritage today.

Types and Features

Bianqing instruments vary in size, shape, and material, depending on the period and cultural context in which they were made. The most common types of Bianqing include:

Material Composition

Jade Bianqing: The most prestigious version of the instrument, made from high-quality jade. These chimes produce a clear, delicate sound and were often used in imperial court music. Jade Bianqing was also considered a symbol of purity and wisdom.

Marble Bianqing: A more common variant, made from finely carved marble or limestone. These chimes were often used in Buddhist temples and Confucian ceremonies.

Bronze Bianqing: Although less common, some Bianqing sets were made from metal instead of stone. These instruments had a different tonal quality and were sometimes used alongside bronze bells in court performances.

Size and Number of Chimes

Small Bianqing Sets contain around 8 to 12 chimes and were typically used for private ceremonies or smaller musical performances. Large Bianqing Sets could include 16 or more chimes and were used in royal courts and religious temples. These sets required skilled musicians to play them properly, as each stone had to be struck with precision.

Work Mechanics

The Bianqing is played by striking the stone chimes with a mallet or specialized percussion stick. The musician carefully selects which chime to hit based on the required pitch and rhythm of the musical piece. Since each stone is precisely tuned to a specific note, the instrument functions like a xylophone or marimba, though its tonal quality is distinct due to the nature of the stone material.

The playing technique involves controlled strikes that allow the stones to resonate fully. Unlike metal bells or wooden instruments, which may produce overtones and sustained reverberations, Bianqing produces a sharp, clear note that fades relatively quickly. Musicians must time their strikes carefully to maintain the flow of music, particularly in ceremonial performances where precise timing is crucial.

In traditional Chinese orchestras, Bianqing players often coordinate with bell players and string musicians to create harmonic and rhythmic complexity. Since the instrument does not allow for dynamic variation in the way that string or wind instruments do, its role is primarily to provide a steady and measured musical foundation.

Role in Music

Bianqing has played a fundamental role in Chinese music for over three thousand years. Its use extends beyond entertainment, as it has been deeply integrated into religious, scholarly, and governmental traditions.

Religious and Ritual Use

Bianqing is most commonly associated with Confucian rituals and Buddhist ceremonies. In Confucianism, music is considered a vital component of moral and social harmony, and Bianqing is often used in ceremonies that honor ancestors or important scholars. The instrument’s clear, measured tones symbolize balance and order, reflecting Confucian ideals of governance and ethics.

In Buddhist traditions, Bianqing is used in temple rituals to accompany chanting and meditation. The resonant sound of the stone chimes is believed to purify the mind and create an atmosphere of serenity. Many Buddhist monasteries in China, Korea, and Japan continue to use variations of Bianqing in their religious practices.

Role in Court and Imperial Music

During the imperial period, Bianqing was an essential instrument in royal court orchestras. It was often played during state ceremonies, banquets, and diplomatic receptions. The instrument’s presence in these events underscored the importance of traditional music in reinforcing political authority and cultural continuity. The Chinese emperors of the Ming and Qing Dynasties maintained elaborate musical ensembles that featured Bianqing prominently.

In addition to court music, Bianqing was also used in traditional Chinese opera and large-scale performances celebrating national festivals. Its role in these events varied, but it was often used to mark transitions between different sections of a performance or to provide a percussive foundation for other melodic instruments.

Significance of Bianqing

Bianqing is more than just a musical instrument; it represents a deep cultural and philosophical tradition within Chinese history. Its significance can be understood in multiple ways:

Symbol of Intellectual and Artistic Refinement

Throughout Chinese history, music was closely linked to scholarly and intellectual life. Bianqing, as a refined and sophisticated instrument, became a symbol of wisdom, education, and cultural sophistication. It was often played in the presence of scholars and philosophers, who appreciated its harmonic precision and meditative qualities.

Connection to Spiritual and Religious Practices

Bianqing’s association with Confucian and Buddhist traditions highlights its spiritual significance. In many temples and monasteries, the instrument is still played as part of daily rituals, reinforcing its enduring role in religious and philosophical traditions.

Preservation of Chinese Musical Heritage

As one of the oldest known Chinese instruments, Bianqing serves as an important link to the country’s musical past. Efforts to preserve and revive traditional Chinese music have included the continued study and performance of Bianqing, ensuring that future generations can appreciate its historical and cultural value.

In modern times, Bianqing is still played in traditional ensembles, university music programs, and cultural exhibitions. It remains an iconic representation of ancient Chinese music and philosophy, embodying the harmony and discipline that have long been central to Chinese thought.

FAQ

How does the Bianqing produce sound?

The Bianqing produces sound when its stone chimes are struck with a mallet. Each stone, depending on its thickness and material, produces a distinct tone. The sound is clear and bright, contributing to the instrument's majestic and calming effect.

What type of music is typically played on the Bianqing?

The Bianqing is typically used in traditional Chinese ritual and court music. It is often played in slow-paced melodies that evoke a sense of calmness and majesty. The instrument is also used in ceremonial music in other Asian countries.

What role does the Bianqing play in traditional Chinese music?

The Bianqing plays a significant role in traditional Chinese music, particularly in ritual and court performances. It is often used alongside other instruments like the Bianzhong to create complex and harmonious melodies. The instrument's use extends beyond China, influencing the traditional music of other Asian cultures.

Links

Links

References

Other Instrument

Categories