Fortepiano

Keyboard Instruments

Europe

Between 1001 and 1900 AD

Video

The fortepiano is an early version of the modern piano, often referred to as the “pianoforte” in its historical context. This instrument bridges the gap between the harpsichord and the contemporary piano, offering a dynamic range that allows for both soft and loud tones, hence its name derived from the Italian words forte (loud) and piano (soft). Unlike its predecessor, the harpsichord, which plucks strings, the fortepiano produces sound by striking strings with leather-covered hammers.

This innovation enabled nuanced dynamics and expressive articulation, making it a pivotal instrument in shaping Classical-era music. The fortepiano is classified as a keyboard chordophone. It operates on a mechanism where keys activate hammers that strike strings to produce sound. The instrument’s design allows for a chromatic range and dynamic control, distinguishing it from earlier keyboard instruments like the harpsichord. The fortepiano is considered the precursor to modern pianos, evolving over time to incorporate features such as extended octave ranges and pedal mechanisms.

History of the Fortepiano

The fortepiano was invented by Bartolomeo Cristofori, an Italian harpsichord maker employed by the Medici family in Florence. Cristofori’s earliest models appeared around 1700, marking a revolutionary departure from plucked-string mechanisms to hammer-striking mechanisms. His invention laid the foundation for a new era in keyboard instruments. The fortepiano gained popularity in Europe during the 18th century, particularly in Italy, Austria, and Germany. Composers such as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Joseph Haydn, Ludwig van Beethoven, and Franz Schubert composed extensively for this instrument. By the late 18th century, technological advancements driven by the Industrial Revolution allowed for more robust designs, contributing to its evolution into the modern piano. In its early stages during the 18th century, fortepianos had limited octave ranges of about four octaves. By Mozart’s time, this expanded to five octaves. Beethoven’s later compositions reflected instruments with six-and-a-half octaves. The fortepiano’s decline began in the early 19th century as heavier and more durable pianos with iron frames emerged. However, interest in historically informed performances revived its use in the 20th century.

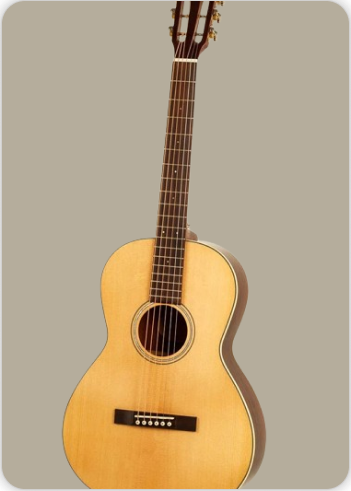

Construction and Design

The fortepiano features a wing-shaped wooden frame housing horizontally positioned strings. Longer strings are accommodated on one side of the instrument while shorter strings are placed on the opposite side. Beneath these strings lies a thin wooden soundboard reinforced with struts to amplify vibrations. The hammers of a fortepiano are smaller and lighter than those of modern pianos. They are covered with leather rather than felt and are suspended inside capsules that allow precise control over dynamics. This design results in a lighter touch and expressive capabilities unique to fortepianos.

Sound Characteristics

Fortepianos produce softer tones with less sustain compared to modern pianos. The bass register has a buzzing quality, while higher registers sound “tinkling.” These tonal differences made them suitable for Classical-era compositions emphasizing clarity and articulation. Early fortepianos had four octaves, which expanded to five octaves during Mozart’s era and six-and-a-half octaves during Beethoven’s later years. Modern pianos have seven-and-a-third octaves. Fortepianos often included mechanisms for altering resonance similar to pedals on modern pianos. Early designs used hand stops or knee levers instead of foot pedals.

Types of Fortepianos

Viennese Fortepianos: Viennese fortepianos were straight-strung instruments popular during Mozart’s time. Their design emphasized light textures and clarity in sound production.

English Fortepianos: English manufacturers like John Broadwood & Sons developed heavier designs with extended ranges and improved resonance mechanisms during the late 18th century.

Replicas and Modern Reconstructions: Modern replicas of historical fortepianos are built for historically informed performances. These replicas adhere closely to 18th-century specifications.

Characteristics of the Fortepiano

The fortepiano allows players to vary sound volume based on touch sensitivity—a feature absent in harpsichords. This dynamic range revolutionized musical expression during its time. The instrument supports legato playing as well as rapid articulations like repeated notes or arpeggios. These capabilities made it versatile for Classical compositions. Fortepianos typically had four pedals operated by foot or knee levers to control sustain, damping, or timbre modifications. Unlike modern pianos with uniform tone quality across registers, fortepianos exhibit distinct tonal variations: buzzing bass notes, tinkling high treble notes, and rounded mid-range tones.

Playing Techniques and Sound Modifications

The fortepiano requires a nuanced playing technique distinct from that of the modern piano. Its lighter touch and smaller dynamic range demand precision and sensitivity. Unlike the modern piano, where force can produce a wide range of dynamics, the fortepiano relies on subtle variations in touch to achieve expressiveness. Players must develop finger independence and wrist flexibility to navigate its delicate keys effectively. Articulation is a key aspect, with staccato notes requiring crisp lifts and legato passages demanding seamless transitions between keys. Sound modifications on the fortepiano are achieved through a combination of touch, pedaling, and phrasing. The instrument often features knee levers or hand stops instead of pedals, which allow players to control dampers or alter tonal qualities. For example, the una corda mechanism shifts the action so that hammers strike fewer strings, producing a softer and more intimate tone. Players must also be adept at using crescendos and decrescendos to shape musical phrases dynamically, compensating for the instrument’s more limited sustain compared to modern pianos.

Additionally, historical performance practices influence technique. Fortepiano players often emulate the phrasing and articulation of string instruments, as these were frequently paired in chamber music settings. This involves balancing dynamics carefully to blend seamlessly with other instruments, creating a cohesive ensemble sound.

Applications in Music

The fortepiano played a central role in 18th- and early 19th-century classical music. Composers like Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert wrote extensively for the instrument, tailoring their compositions to its unique tonal palette. Its ability to produce both delicate and dramatic sounds made it ideal for solo works, chamber music, and early concertos. In solo repertoire, the fortepiano’s dynamic subtleties allow performers to convey intricate emotional landscapes. Works such as Beethoven’s early piano sonatas or Mozart’s keyboard concertos highlight its expressive capabilities. In chamber music, it often served as an equal partner to string instruments rather than merely an accompaniment tool. For example, Mozart’s piano trios and Beethoven’s violin sonatas showcase the interplay between fortepiano and strings. The fortepiano also played a pivotal role in shaping musical forms like the sonata-allegro structure. Its dynamic range enabled composers to experiment with contrasts between themes and sections, laying the groundwork for later developments in classical music. Today, the fortepiano is used primarily in historically informed performances (HIP). Musicians specializing in early music use it to recreate authentic interpretations of classical works. Its revival has enriched our understanding of how composers intended their music to sound.

Most Influential Players

Several performers have significantly contributed to the fortepiano’s legacy:

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: As both a composer and performer, Mozart showcased the expressive potential of the fortepiano in his concertos and sonatas.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Beethoven pushed the instrument’s capabilities to their limits, using its dynamic range and tonal qualities to create groundbreaking works like his early sonatas.

András Schiff: A modern pianist known for his historically informed performances on period instruments.

Malcolm Bilson: A leading figure in the fortepiano revival movement who has extensively recorded classical repertoire using original instruments.

Kristian Bezuidenhout: Renowned for his interpretations of Mozart’s works on fortepiano, Bezuidenhout has brought new life to historical performance practices.

These artists have not only preserved but also expanded our appreciation for this unique instrument.

Maintenance and Care

Proper maintenance is essential for preserving the delicate mechanics of a fortepiano. Unlike modern pianos, which are built for durability, fortepianos are more fragile due to their lighter construction and historical materials.

Tuning: Regular tuning is crucial since the strings are more prone to detuning due to environmental changes. The pitch standard for fortepianos is often lower than modern concert pitch (A=440 Hz), aligning with historical practices.

Humidity Control: Maintaining stable humidity levels prevents wood warping or cracking. Fortepianos should be kept in environments with moderate humidity (around 40–50%).

String Maintenance: Strings should be inspected regularly for rust or wear. Replacement requires specialized knowledge due to differences in string gauges compared to modern pianos.

Action Mechanism: The action mechanism needs periodic adjustment to ensure smooth key response. This involves regulating hammer alignment and damper function.

Cleaning: Dust accumulation can affect sound quality and mechanics. A soft cloth should be used to clean surfaces gently without damaging finishes or components.

Owners often consult specialists trained in historical instruments for repairs or restorations since these require expertise beyond standard piano maintenance.

Cultural Significance

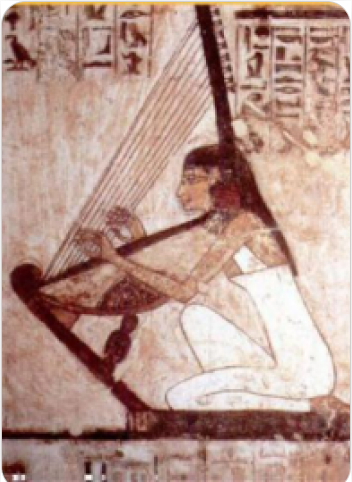

The fortepiano holds significant cultural importance as a bridge between earlier keyboard instruments like the harpsichord and modern pianos. It symbolizes a period of musical innovation during which composers began exploring greater emotional depth and dynamic contrast in their works. In 18th-century Europe, the fortepiano became an emblem of domestic music-making among aristocratic families. Its versatility made it suitable for both formal concerts and intimate gatherings. As public concerts grew in popularity during this era, the instrument also became central to emerging virtuoso culture.

The revival of interest in historical performance practices during the 20th century brought renewed attention to the fortepiano’s role in shaping classical music traditions. Institutions such as conservatories now include period instrument studies in their curricula, ensuring that future generations understand its significance. Moreover, festivals dedicated to early music often feature fortepiano performances, highlighting its enduring appeal among audiences seeking authentic interpretations of classical repertoire.

FAQ

What are the main features of the Fortepiano?

The Fortepiano has a wooden frame, thin strings, and leather-covered hammers. It offers dynamic control, allowing both soft and loud sounds. It has a lighter touch compared to modern pianos. Early models had knee levers instead of foot pedals.

How does the Fortepiano differ from the modern piano?

The Fortepiano has a smaller range (5-6 octaves), a lighter structure, and a softer tone. Unlike modern pianos, it uses wooden frames and leather-covered hammers. It produces a more delicate sound, ideal for classical-era music. The modern piano has a cast-iron frame and felt hammers.

What is the historical significance of the Fortepiano?

Invented in the early 18th century by Bartolomeo Cristofori, the Fortepiano revolutionized keyboard music. It allowed expressive dynamics, shaping classical compositions. It was favored by composers like Mozart and Beethoven. By the 19th century, it evolved into the modern piano.

Links

Links

References

Other Instrument

Categories