Guqin

Plucked Instruments

Asia

Ancient

Video

The guqin, also known as the qin, is a plucked seven-string Chinese musical instrument of the zither family. It is revered as one of the oldest Chinese musical instruments with a history spanning over three millennia. The guqin is not merely a musical instrument; it is a symbol of Chinese high culture, philosophy, and spirituality. Its sound, often described as subtle, introspective, and profound, is meant to evoke a sense of contemplation and harmony with nature. Unlike the more flamboyant sounds of other Chinese instruments, the guqin’s tone is delicate and nuanced, requiring attentive listening. Its music is traditionally associated with scholars, sages, and recluses, and it has played a significant role in Chinese literary and philosophical traditions. Playing the guqin is considered a form of self-cultivation, a way to purify the mind and connect with the deeper aspects of existence. The instrument’s aesthetic, from its elegant shape to the intricate inlays and lacquer finish, reflects the refined sensibilities of the Chinese literati.

Type of Instrument

The guqin is classified as a chordophone, specifically a plucked zither. It belongs to the broader family of zithers, which are instruments with strings stretched across a soundboard. However, the guqin’s unique construction and playing techniques distinguish it from other zithers. It is a fretless instrument, meaning that the player presses the strings directly onto the soundboard to produce different pitches. This allows for a wide range of subtle pitch variations and expressive nuances, including slides, vibratos, and harmonics. The guqin’s seven strings are traditionally made of silk, although modern instruments may use nylon or steel strings. The strings are stretched over a long, curved soundboard, which is typically made of paulownia wood. The instrument is played by plucking the strings with the fingers of the right hand and pressing the strings with the fingers of the left hand. This combination of plucking and pressing allows for a complex and expressive range of sounds.

Historical Background

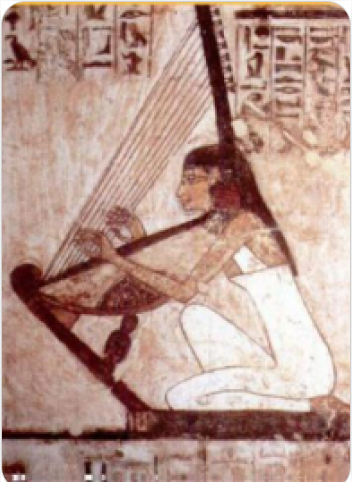

The guqin’s history is deeply intertwined with the development of Chinese civilization. Originating in East Asia, specifically in what is now modern-day China, its earliest forms can be traced back to the Zhou Dynasty (11th-3rd centuries BCE). Legends attribute its invention to mythical figures such as Fuxi and Shun, suggesting its ancient origins. By the Spring and Autumn period (771-476 BCE) and the Warring States period (475-221 BCE), the guqin had become an instrument of the elite, associated with scholars and philosophers. Confucius himself is said to have been a skilled guqin player, and its music was considered an essential part of a gentleman’s education. During the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE), the guqin’s status as a scholarly instrument was further solidified. The “Shijing” (Classic of Poetry) and other ancient texts contain numerous references to the guqin, indicating its widespread popularity. The instrument’s development continued through the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE), a golden age of Chinese culture, during which many famous guqin pieces were composed. The Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE) saw the production of numerous guqin manuals and treatises, which documented playing techniques, musical notation, and the instrument’s philosophy. The Ming (1368-1644 CE) and Qing (1644-1912 CE) dynasties witnessed further refinements in guqin construction and playing styles. However, the 20th century brought significant challenges to the guqin tradition. Political upheavals, including the Cultural Revolution, led to a decline in its popularity. Nevertheless, dedicated musicians and scholars have worked to preserve and revive the guqin tradition, and it has experienced a resurgence in recent decades. In 2003, the guqin and its music were proclaimed a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO, recognizing its cultural significance.

Construction and Design

The guqin’s construction and design are meticulously crafted, reflecting the instrument’s philosophical and aesthetic values. The soundboard, typically made of paulownia wood, is the most critical component. Paulownia is chosen for its light weight, resonant qualities, and beautiful grain. The underside of the soundboard usually features two sound holes, known as the “dragon pool” and the “phoenix pond,” which contribute to the instrument’s resonance. The soundboard is slightly arched, which enhances its vibrational properties. The guqin’s body is typically constructed from two pieces of wood: the soundboard and the bottom board, often made of catalpa or cypress. The two boards are glued together, and the edges are carefully shaped and smoothed. The guqin’s surface is finished with multiple layers of lacquer, which not only protects the wood but also enhances its tonal qualities. The lacquer finish can take months or even years to complete, involving numerous applications and drying periods. The guqin’s seven strings are stretched over a nut at the head of the instrument and a bridge at the tail. The strings are anchored to tuning pegs at the head and pass over thirteen studs, or hui, which are inlaid markers that indicate harmonic positions. The hui are traditionally made of mother-of-pearl or jade. The guqin’s shape is often described as resembling a reclining human body, with the head, neck, shoulders, waist, and tail represented by different parts of the instrument. The guqin’s design is not only aesthetically pleasing but also functional, contributing to its unique sound and playing characteristics. The guqin’s length is normally around 120-125cm.

Types of Guqin

While the basic structure of the guqin remains consistent, there are variations in size, shape, and construction that have evolved over time. These variations can be broadly categorized into different types, each with its own characteristics and historical associations. One common classification is based on the shape of the soundboard. For example, the “Fuxi-style” guqin features a straight, rectangular soundboard, while the “Zhongni-style” guqin has a more rounded and curved soundboard. Another classification is based on the size of the instrument. Larger guqins, known as “long qin,” tend to have a deeper and more resonant sound, while smaller guqins, known as “short qin,” are more portable and may have a brighter tone. Variations also exist in the number and placement of the hui, although the standard arrangement of thirteen hui is most common. Some guqins may feature additional decorative elements, such as intricate carvings or inlays, which reflect the craftsmanship and aesthetic preferences of their makers. Historically, guqins were often custom-made for individual players, resulting in a wide range of variations in design and construction. The choice of materials, the thickness of the soundboard, and the type of lacquer used can all influence the instrument’s sound and playing characteristics. Modern guqin makers often draw inspiration from historical models while incorporating their own innovations and refinements.

Characteristics

The guqin’s characteristics are deeply rooted in its philosophical and aesthetic values. Its sound is often described as subtle, introspective, and profound, reflecting the instrument’s association with contemplation and self-cultivation. The guqin’s tone is delicate and nuanced, requiring attentive listening to appreciate its full range of expression. Unlike the more flamboyant sounds of other Chinese instruments, the guqin’s music is meant to evoke a sense of tranquility and harmony with nature. The guqin’s playing techniques are highly complex and expressive, allowing for a wide range of pitch variations, dynamics, and timbres. The use of slides, vibratos, and harmonics allows the player to create a rich and varied soundscape. The guqin’s music is often characterized by its use of silence and space, which are considered as important as the notes themselves. The pauses and silences between phrases allow the listener to reflect on the music and connect with its deeper meaning. The guqin’s music is also characterized by its use of pentatonic scales and modal harmonies, which create a sense of simplicity and naturalness. The guqin’s repertoire consists of a wide range of pieces, from ancient melodies to contemporary compositions. Many guqin pieces are programmatic, meaning that they tell a story or depict a scene from nature. Others are more abstract, focusing on the exploration of musical ideas and emotions.

The guqin’s music is often associated with Chinese literature and philosophy, and many pieces are based on classical texts or poems. The guqin’s playing style is highly personal and expressive, reflecting the individual player’s interpretation of the music. Each player brings their own unique sensibility and understanding to the instrument, resulting in a wide range of interpretations of the same piece. The guqin is not merely a musical instrument; it is a vehicle for self-expression and spiritual exploration. Its music is meant to be experienced not only with the ears but also with the heart and mind. The guqin’s sound is soft, so typically it is played in a silent environment. The guqin’s sound is considered to be the sound of the sage.

Playing Techniques and Sound Modifications

The guqin’s playing techniques are intricate and nuanced, requiring years of dedicated practice to master. The instrument is played by plucking and stopping the strings with the fingers of the right and left hands, respectively. The right hand employs a variety of plucking techniques, each producing a distinct tonal quality. These techniques include “pi” (plucking outwards), “tiao” (plucking inwards), “mo” (rubbing), and “gou” (hooking). The left hand, meanwhile, manipulates the strings by pressing them against the soundboard at specific positions, creating a range of pitches and timbres. These positions, known as “hui” (studs), are marked by small inlaid dots along the soundboard, providing a visual guide for the player. The left hand techniques include “an” (pressing), “rou” (rubbing), “yin” (vibrato), and “fan yin” (harmonics). “Fan yin” is a particularly distinctive feature of guqin playing, achieved by lightly touching the string at a hui while plucking it, producing a clear, ethereal tone. The combination of these right and left hand techniques allows the player to create a vast array of sounds, from delicate whispers to resonant chords. Sound modifications are also achieved through the use of different finger positions and pressures, as well as by varying the speed and intensity of the plucking. The guqin’s construction, with its curved soundboard and silk strings, contributes to its unique resonance and sustain. The silk strings, in particular, produce a warm, mellow tone that is distinct from the brighter sound of modern metal strings. The instrument’s resonance is further enhanced by its hollow body, which acts as a sound chamber, amplifying the vibrations of the strings. The player can also modify the sound by using different parts of the fingers or nails to pluck the strings, and by adjusting the angle and pressure of the plucking motion. The guqin’s versatility allows for a wide range of expressive possibilities, enabling the player to convey a spectrum of emotions and moods.

Applications in Music

The guqin’s applications in music are deeply rooted in its historical and cultural context. It was traditionally played as a solo instrument, primarily for personal enjoyment and contemplation. Its intimate and introspective nature made it unsuitable for large ensembles or public performances. Instead, it was often played in quiet settings, such as gardens, tea houses, or private studios, where its subtle tones could be fully appreciated. The guqin was closely associated with the literati, who used it as a means of self-expression and spiritual cultivation. It was believed that playing the guqin could purify the mind, calm the spirit, and foster a connection with the natural world. Many guqin pieces are inspired by nature, reflecting the beauty of mountains, rivers, and forests. These pieces often feature descriptive titles, such as “Flowing Water” or “Wild Geese Descending on the Sandbank,” and their music evokes vivid images of the natural world. The guqin was also used in ritual and ceremonial contexts, particularly in Confucian ceremonies and Daoist rituals.

Its solemn and dignified sound was considered appropriate for these occasions, where it served to create an atmosphere of reverence and contemplation. In modern times, the guqin has experienced a revival, with increasing interest in its traditional music and playing techniques. It is now being used in a wider range of musical contexts, including contemporary compositions, film scores, and cross-cultural collaborations. While still primarily a solo instrument, the guqin is also being incorporated into chamber music and other ensemble settings, expanding its musical possibilities. The instrument’s unique sound and cultural significance continue to inspire composers and musicians, ensuring its relevance in the contemporary music scene.

Most Influential Players

Throughout its long history, the guqin has been played by numerous influential musicians, each contributing to its development and preservation. One of the most legendary figures is Bo Ya, a musician from the Spring and Autumn period (771-476 BCE), whose friendship with Zhong Ziqi is celebrated in the famous story of “High Mountains and Flowing Water.” This tale highlights the deep connection between music and friendship, and it has become an enduring symbol of the guqin’s power to express profound emotions. Ji Kang (223-263 CE), a renowned scholar and musician of the Wei Dynasty, was another influential figure. He was known for his virtuosity and his independent spirit, and his guqin compositions, such as “Guangling San,” are considered masterpieces of the repertoire. In the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE), Chen Zhuo, a court musician, made significant contributions to guqin notation and performance practice. In the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE), Zhu Xi, a prominent Neo-Confucian philosopher, was also a skilled guqin player and composer. His works, such as “Ping Sha Luo Yan” (Wild Geese Descending on the Sandbank), are still widely performed today. In the Ming and Qing Dynasties (1368-1912 CE), numerous schools and styles of guqin playing emerged, each with its own distinctive characteristics. Notable players from this period include Xu Qingshan, Zhu Quan, and Peng Xiuwen. In the 20th and 21st centuries, figures like Guan Pinghu, Zha Fuxi, and Wu Jinglue have played crucial roles in preserving and promoting the guqin tradition. Guan Pinghu, in particular, was instrumental in recording and transcribing many ancient guqin pieces, ensuring their survival for future generations. These influential players have not only mastered the guqin’s techniques but also deepened its cultural significance through their interpretations and compositions. Their dedication to the instrument has ensured its continued relevance and appreciation in the modern world.

Maintenance and Care

The guqin is a delicate instrument that requires careful maintenance and care to preserve its sound and longevity. Its silk strings are particularly sensitive to changes in temperature and humidity, and they can be easily damaged by excessive tension or rough handling. The instrument should be stored in a dry, well-ventilated place, away from direct sunlight and extreme temperatures. It is important to avoid placing the guqin near heaters, air conditioners, or other sources of heat or cold. The strings should be regularly checked for wear and tear, and replaced as needed. The soundboard should be cleaned with a soft, dry cloth to remove dust and fingerprints. The guqin should be played with clean hands to prevent the accumulation of dirt and oil on the strings and soundboard. It is also important to avoid touching the strings with sharp objects, as this can damage them. The bridge and pegs should be checked regularly for stability and adjusted as needed. The guqin should be tuned regularly to maintain its pitch and intonation. The tuning process involves adjusting the tension of the strings using the pegs and the bridge. It is important to use a reliable tuner and to proceed with caution, as excessive tension can damage the strings or the instrument. For major repairs or maintenance, it is recommended to consult a qualified guqin luthier. They will be able to assess the condition of the instrument and perform any necessary repairs or adjustments. Proper maintenance and care will ensure that the guqin remains in good condition and continues to produce its beautiful and expressive sound for many years to come.

Cultural Significance

The guqin’s cultural significance in China cannot be overstated. It is far more than a musical instrument; it is a symbol of Chinese philosophy, aesthetics, and spirituality. The guqin was an integral part of the literati culture, representing the ideal of the cultivated scholar. It was believed that playing the guqin could cultivate moral character, refine one’s taste, and foster a connection with the natural world. The instrument’s association with Confucianism and Daoism has further enhanced its cultural significance. Confucian ideals of harmony, balance, and self-cultivation are reflected in the guqin’s music and playing techniques. Daoist principles of simplicity, naturalness, and inner peace are also evident in the instrument’s sound and aesthetics.

The guqin was often used in rituals and ceremonies, particularly in Confucian ceremonies and Daoist rituals. Its solemn and dignified sound was considered appropriate for these occasions, where it served to create an atmosphere of reverence and contemplation. The guqin’s cultural significance is also reflected in its literature and art. Numerous poems, essays, and paintings have been inspired by the guqin, celebrating its beauty and its ability to evoke profound emotions.

FAQ

What are the main features of the Guqin?

The Guqin is a plucked seven-string zither with no frets, known for its rich harmonics, deep resonance, and sliding tones. It has a range of over four octaves and uses complex finger techniques. Traditionally, it has 13 inlaid markers for finger positioning. The instrument is often associated with scholars and meditative music.

What materials are used to construct the Guqin?

The Guqin is made of a wooden soundboard, traditionally using Paulownia or Catalpa wood, with a bottom board of Chinese fir. The surface is coated with layers of lacquer mixed with powdered deer antler. Silk strings were originally used, but modern versions may use nylon-wound metal strings.

What are the primary uses and applications of the Guqin?

The Guqin is primarily used for solo performances, meditation, and scholarly gatherings, emphasizing introspection and refinement. It is also played in ensemble settings with traditional Chinese instruments. Historically, it was a symbol of the literati class and is still used in cultural and ceremonial events.

Links

Links

References

Other Instrument

Categories