Ichigenkin

Plucked Instruments

Asia

Between 0 and 1000 AD

Video

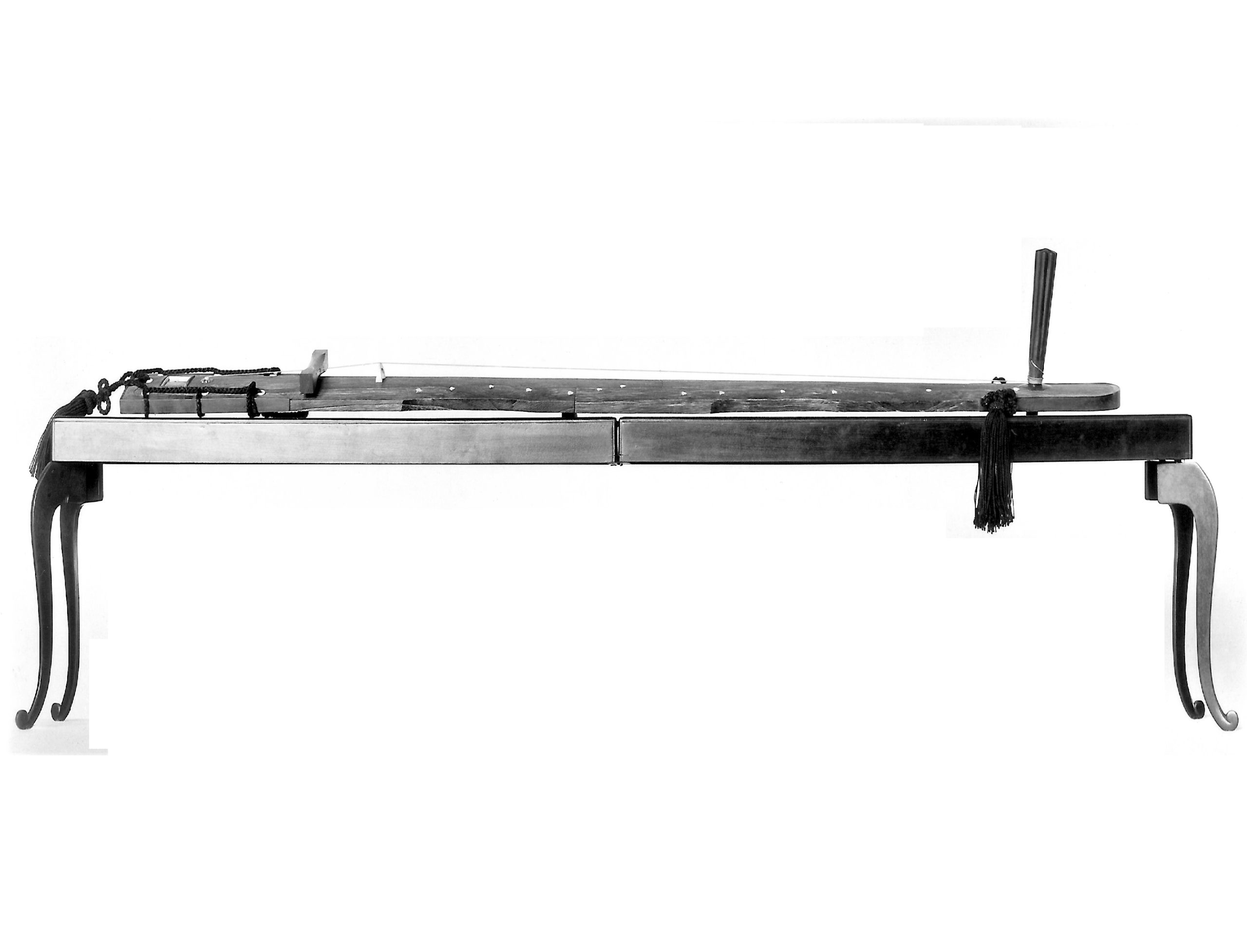

The ichigenkin, a singular and profoundly evocative musical instrument, stands as a testament to the enduring power of simplicity in artistic expression. Its very name, translating to “one-string zither,” encapsulates its fundamental nature. This instrument, rooted in Japanese tradition, offers a unique sonic landscape, characterized by its delicate tones and contemplative resonance. It is more than just a musical tool; it is a cultural artifact, a philosophical conduit, and a historical echo, resonating with the spirit of ancient Japan.

Description and Type of Instrument

The ichigenkin is classified as a zither, specifically a long, plucked box zither. Its defining feature is its single string, stretched across a long, hollow soundbox. This simple construction belies the instrument’s capacity for intricate and nuanced musical expression. The sound produced is often described as ethereal, subtle, and deeply introspective, reflecting the instrument’s historical association with meditation and spiritual practice. The ichigenkin is played by plucking the string with the fingers or a plectrum, while the left hand manipulates the string’s tension using a series of frets or markers, creating a range of pitches. The soundbox, typically made of resonant wood, amplifies the vibrations of the string, producing a soft, mellow tone. The instrument’s minimalist design emphasizes the purity of sound and the performer’s ability to extract a wide range of timbres from a single string. The player’s interaction with the instrument is highly personal, demanding a deep understanding of its sonic capabilities and a refined sense of touch. The ichigenkin is not merely a source of musical notes but a vehicle for emotional and spiritual expression, inviting both the performer and the listener into a space of quiet contemplation.

History and Origin

The ichigenkin’s history is deeply intertwined with the cultural and philosophical traditions of Japan. While its exact origins remain somewhat shrouded in mystery, it is believed to have originated in China during the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) as a form of the guqin, a seven-stringed zither. The guqin was brought to Japan during the Nara period (710-794 CE) and Heian period (794-1185 CE), along with many other aspects of Chinese culture, including Buddhism and Confucianism. Over time, the guqin underwent transformations in Japan, ultimately leading to the development of the ichigenkin. The ichigenkin’s emergence as a distinct instrument is generally attributed to the Kamakura period (1185-1333 CE) and the Muromachi period (1336-1573 CE), a time of significant cultural and artistic development in Japan. During this period, the instrument became associated with Zen Buddhism and the practice of meditative music. It was favored by monks and scholars, who valued its simplicity and its ability to facilitate introspection. The ichigenkin’s association with Zen philosophy is evident in its minimalist design and its emphasis on the beauty of silence and the subtle nuances of sound. The instrument’s history is not one of widespread popularity but rather of quiet cultivation within specific cultural and spiritual circles. Its legacy is preserved through the dedicated efforts of practitioners and scholars who continue to explore its unique sonic potential. The ichigenkin has remained a niche instrument, its tradition passed down through generations of dedicated performers, ensuring its survival in the modern era.

Construction and Design

The construction of the ichigenkin is characterized by its simplicity and elegance. The primary component is the long, rectangular soundbox, typically made of paulownia wood (kiri), a lightweight and resonant material. The soundbox is hollow, with a soundhole on the underside to enhance the instrument’s resonance. The single string, traditionally made of silk, is stretched across the soundbox, anchored at both ends by pegs or bridges. The string’s tension can be adjusted to alter the pitch and tone. The playing surface of the soundbox is often lacquered, providing a smooth and durable surface for the performer’s fingers. The instrument may also feature a series of markers or frets, typically made of ivory or bamboo, which indicate the positions for different pitches. These markers are not always fixed, allowing the performer to adjust them according to their preference and the specific musical piece. The design of the ichigenkin emphasizes the natural beauty of the materials and the craftsmanship involved. The instrument’s minimalist aesthetic reflects the Zen philosophy that values simplicity and the appreciation of natural forms. The soundbox’s dimensions and shape are carefully considered to optimize the instrument’s resonance and tonal quality. The ichigenkin is often decorated with subtle and understated motifs, such as lacquer designs or inlaid patterns, reflecting the refined tastes of its practitioners. The instrument’s construction is a testament to the skill and artistry of traditional Japanese craftsmen, who have preserved the techniques and materials used in its creation for centuries.

Types of Ichigenkin

While the ichigenkin is fundamentally a single-string zither, there are subtle variations in its design and construction, reflecting regional differences and the preferences of individual performers. These variations, however, do not create distinct “types” in the sense of significantly different instruments. Instead, they represent minor adjustments to the basic design, primarily concerning the materials used, the dimensions of the soundbox, and the placement of the markers. For example, some ichigenkin may feature a slightly curved soundbox, while others have a perfectly flat surface. The type of wood used for the soundbox can also vary, although paulownia is the most common choice. The length and thickness of the string can also be adjusted, affecting the instrument’s tone and pitch range. The placement and number of markers may also vary, depending on the performer’s preference and the musical style being played. Some ichigenkin may have a more elaborate finish, with intricate lacquer work or inlaid designs, while others are kept simple and unadorned. These variations, while subtle, can contribute to the unique character and sound of each individual ichigenkin. The instrument’s adaptability allows performers to personalize their instruments, reflecting their own artistic sensibilities and musical preferences. However, the fundamental principles of the ichigenkin’s construction and design remain consistent across these variations, ensuring the preservation of its essential character.

Characteristics

The ichigenkin’s characteristics are deeply rooted in its minimalist design and its association with Zen Buddhism. Its most prominent characteristic is its single string, which produces a delicate and ethereal sound. The instrument’s tone is often described as soft, mellow, and introspective, inviting the listener into a space of quiet contemplation. The ichigenkin’s limited pitch range, due to its single string, encourages performers to explore the subtle nuances of tone and timbre. The instrument’s expressiveness lies not in its ability to produce a wide range of notes but in its capacity to convey subtle emotional and spiritual states. The ichigenkin’s sound is highly sensitive to the performer’s touch, allowing for a wide range of dynamic and tonal variations. The instrument’s resonance is also a crucial characteristic, contributing to its warm and enveloping sound.

The ichigenkin’s association with Zen Buddhism is evident in its emphasis on silence and the appreciation of subtle sounds. The instrument’s minimalist design and its contemplative sound encourage performers and listeners to focus on the present moment and to cultivate a sense of inner peace. The ichigenkin’s characteristics are not limited to its sonic qualities but also extend to its visual aesthetic. The instrument’s simple and elegant design reflects the Zen philosophy that values simplicity and the appreciation of natural forms. The ichigenkin’s characteristics contribute to its unique place in the world of music, distinguishing it from other stringed instruments. Its ability to evoke a sense of tranquility and introspection makes it a valuable tool for meditation and spiritual practice. The ichigenkin’s legacy is one of quiet beauty and profound expressiveness, a testament to the enduring power of simplicity in artistic expression. The instrument’s unique characteristics have allowed it to survive throughout the centuries, passed down through generations of dedicated performers, ensuring its continued presence in the world of music. The delicate and profound nature of the instrument provides an experience that is both moving and deeply personal.

The ichigenkin’s sound, in its simplicity, carries a wealth of emotion, showing that even the simplest of tools can create the most complex of feelings. The instrument’s quiet power is a testament to its cultural importance and the skill of those who play it. The ichigenkin is a reminder that beauty can be found in simplicity and that even a single string can create a world of sound.

Playing Techniques and Sound Modifications

Playing the ichigenkin demands a high degree of technical skill and a profound sensitivity to the instrument’s unique sonic characteristics. The player typically sits in a seiza position, holding the instrument horizontally across their lap. The left hand manipulates the single string, primarily by pressing and sliding, thereby altering the pitch. The right hand employs various techniques, including plucking with the fingernail, striking with a plectrum (often made of ivory or bamboo), or using the back of the hand to produce resonant vibrations. The absence of frets or markers on the instrument’s body necessitates a highly developed sense of pitch and precise hand movements. Subtle variations in finger pressure, hand placement, and plucking technique allow for a wide range of timbral nuances. Glissando, vibrato, and portamento are integral to the ichigenkin’s expressive vocabulary, enabling players to create fluid and evocative melodic lines. Sound modifications are achieved through several methods. The pressure and placement of the left-hand fingers along the string alter the pitch and timbre significantly. A more intense pressure results in a sharper tone, whilst a lighter pressure allows for smoother transitions between pitches. The angle of the plectrum also affects the sound. By changing the angles of the plectrum strike, tones can be altered from sharp to mellow, and many sound qualities inbetween. The use of the back of the hand to dampen the string produces muted, percussive effects. Furthermore, musicians skillfully use the resonating cavity, the hollow body of the ichigenkin, by closing or opening spaces under the bridge, with their hands, and with other objects. This process produces very noticeable differences in sound quality, volume, and reverberation. Players also master a variety of vibrato techniques, varying the speed and width of the vibrato to enhance the expressive quality of their performance. Complex and subtle sound modifications are vital to the rich range of expression possible on the ichigenkin.

Applications in Music

The ichigenkin’s musical applications, while relatively specialized, encompass a range of traditional and contemporary genres. Historically, it was deeply rooted in solo performances, often associated with meditative and contemplative settings. The instrument’s introspective quality made it particularly suitable for conveying philosophical ideas and personal emotions. Classical ichigenkin repertoire often comprises pieces based on traditional melodies, Zen Buddhist chants, and compositions inspired by nature. More recently, the ichigenkin has found its way into contemporary music, where it is used to create unique sonic textures and explore unconventional musical landscapes. Contemporary composers and performers are exploring its capabilities in experimental music, improvisational genres, and collaborations with other traditional and modern instruments. Artists utilize the ichigenkin to generate atmospheric soundscapes, minimalist patterns, and avant-garde compositions. In ensemble contexts, the ichigenkin is sometimes combined with other traditional Japanese instruments, such as the shakuhachi or koto, creating a rich and nuanced sonic tapestry. Furthermore, its sonic character has appealed to ambient musicians, and composers seeking unique tonal colours within their compositions. The delicate and subtle qualities of the instrument make it a very attractive option when a artist wants to achieve an organic and earthy sound. There are some cases of it being incorporated in film scores, because of it’s capacity to induce an atmosphere of peace and introspection.

Most Influential Players

The history of ichigenkin performance is marked by a lineage of dedicated practitioners who have preserved and refined the instrument’s traditions. While mainstream recognition may be limited compared to other Japanese musical arts, certain individuals have played pivotal roles in shaping the ichigenkin’s legacy. Historically, figures associated with Zen Buddhist temples and scholarly circles are acknowledged as early masters, contributing to the development of specific playing styles and repertoires. In more recent times, notable performers have emerged who have dedicated their lives to mastering the instrument. While there isn’t as much mainstream documentation concerning specific historically renowned figures, the transmission of skills was heavily focused on the student teacher model. Therefore knowledge and practice was passed down from generation to generation by dedicated practitioners.

Contemporary performers have continued to broaden the scope of ichigenkin music, both in terms of repertoire and playing techniques. These artists have not only preserved traditional forms but also explored new possibilities for the instrument, bringing it to the attention of wider audiences through recordings, performances, and collaborations. They often engage in academic studies and research, to document the long legacy of the instrument. Through concerts, workshops, and recordings, they perpetuate the knowledge of the instrument. They are important advocates of the instrument, pushing for the continued practice and understanding of Ichigenkin.

Maintenance and Care

The ichigenkin, like any finely crafted musical instrument, requires meticulous maintenance and care to ensure its longevity and optimal performance. The single silk string is particularly susceptible to damage from humidity, temperature fluctuations, and physical stress. Regular replacement of the string is essential, typically performed by a skilled luthier or experienced player. The wooden body of the instrument, usually constructed from high-quality timbers such as paulownia, should be kept clean and protected from excessive moisture and direct sunlight. It is recommended to store the ichigenkin in a padded case or bag when not in use. Periodic inspection of the bridge, tuning pegs, and other structural components is necessary to identify and address any potential issues. Cleaning the wooden body of the instrument should be done with soft cloths, using gentle polishing, and appropriate specialized products. The silk strings are delicate, and must be cleaned with soft dry cloths to prevent the deterioration that can be caused by the oils from hands. The tuning pegs must be checked to insure that slippage doesn’t occur, and the bridges of the instrument should be maintained for structural integrity. Environmental conditions should be maintained for the instrument, as major fluctuation of humidity can cause issues. The ichigenkin’s maintenance underscores the importance of a deep appreciation for the craftsmanship and materials that go into its construction.

Cultural Significance

The ichigenkin occupies a unique space within the rich tapestry of Japanese cultural traditions, reflecting a confluence of philosophical, aesthetic, and spiritual values. Its single-stringed simplicity embodies the Zen Buddhist principle of minimalism and directness, emphasizing the pursuit of inner peace and enlightenment through focused contemplation. The instrument’s association with scholarly and aristocratic circles highlights its role in fostering intellectual and artistic refinement. The ichigenkin’s introspective character resonates with the Japanese aesthetic of wabi-sabi, which celebrates the beauty of imperfection and transience. The slow, meditative tempos and subtle timbral nuances of ichigenkin music evoke a sense of tranquility and connection to nature, reflecting the profound reverence for the natural world that permeates Japanese culture.

The ichigenkin has held, and continues to hold a position of cultural importance, because it represents much more than a musical instument. It serves as a representation of traditional Japanese values, and their unique artistic expression. Through it’s very construction and it’s resulting sound, it provides a means to cultural study. Many scholars have focused studies on the cultural importance of the ichigenkin, in an effort to save the art, and tradition. The ichigenkin also represents the connection to older, classical Japanese ideals, within the modern world. In this way, its cultural significance can be viewed as an anchor to historical Japanese ideals. In short, its continued performance and preservation serve as a vital link to the country’s cultural heritage.

FAQ

What is the history of the Ichigenkin?

The Ichigenkin is a rare Japanese monochord zither, developed in the Edo period (17th century). It was primarily played by monks and samurai for meditative and artistic purposes. Over time, its use declined but was preserved by dedicated practitioners. Today, it remains a niche instrument with a small number of skilled players.

What materials are used in constructing the Ichigenkin?

The Ichigenkin is traditionally crafted from a single piece of paulownia wood for its resonance. The single string is made of silk or modern nylon, and the bridges are typically ivory or wood. Players use a tubular plectrum on their finger to produce its characteristic sliding tones. Simplicity in materials enhances its unique, ethereal sound.

How is the Ichigenkin played?

The Ichigenkin is played by pressing the string with a metal or ivory finger tube while plucking with a plectrum. This technique allows for subtle pitch bends and expressive slides. Unlike other zithers, it emphasizes minimalist, meditative tones. The instrument is played solo, focusing on delicate tonal nuances.

Links

Links

References

Other Instrument

Categories