Kora

Plucked Instruments

Africa

Between 1001 and 1900 AD

Video

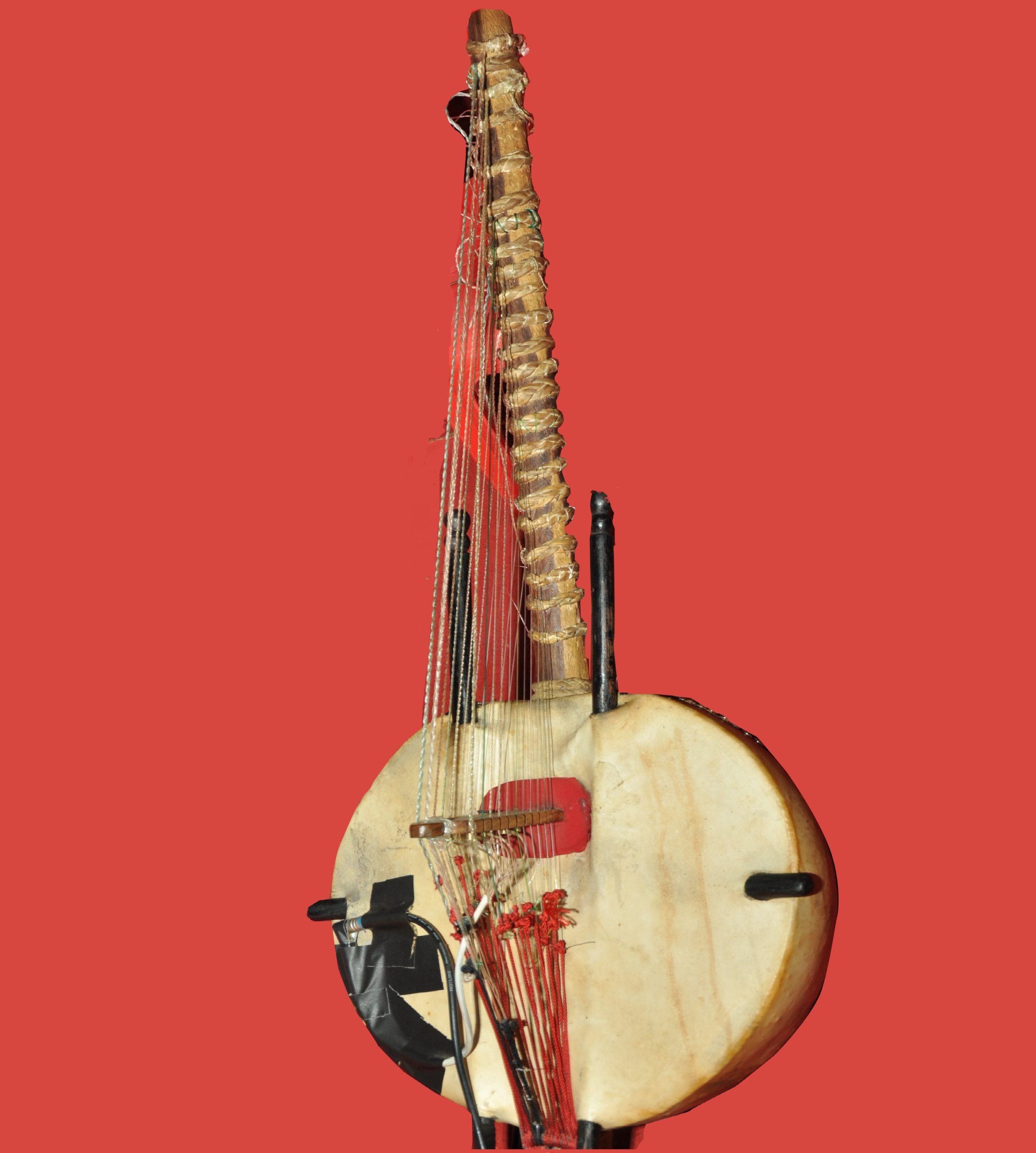

The kora is a captivating 21-string bridge-harp, originating from West Africa, that holds a prominent place in the region’s musical heritage. Its distinctive sound, a blend of harp-like melodies and lute-like rhythmic patterns, resonates deeply with the cultural identity of the Mandinka people and neighboring ethnic groups. The instrument’s visual appearance is equally striking, featuring a large calabash gourd resonator covered with cow skin, a long hardwood neck, and two rows of strings that run perpendicular to the soundboard. The kora’s unique design and intricate playing techniques contribute to its mesmerizing and soulful sound, making it a central instrument in both traditional and contemporary West African music.

Type of Instrument

The kora is classified as a double bridge-harp or a spike harp-lute.

This classification stems from its combination of characteristics found in both harps and lutes. Like a harp, it features strings that are plucked perpendicularly to the soundboard, producing a rich, resonant tone. However, it also shares similarities with lutes in its construction, particularly its long neck and the method of tuning the strings. The double-bridge design, with two rows of strings running along either side of the bridge, further distinguishes the kora from other harp-like instruments. The bridge itself is a crucial element, acting as a fulcrum for the strings and transferring their vibrations to the calabash resonator. The spike harp aspect comes from the neck going through the calabash. The hybrid nature of the kora’s design allows it to produce a wide range of musical textures, from delicate melodic lines to complex rhythmic patterns, contributing to its versatility and enduring appeal.

History of the Kora

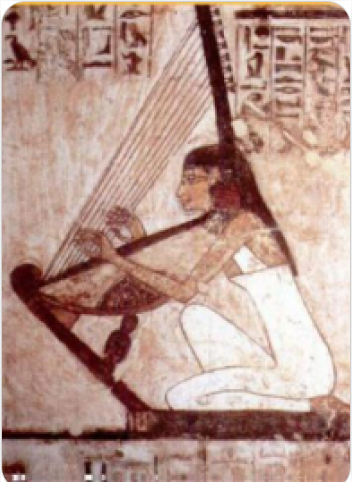

The kora’s history is deeply intertwined with the Mandinka people of West Africa, whose oral traditions trace its origins back centuries. While precise dates and events are difficult to pinpoint due to the lack of written records, it is generally believed that the kora emerged sometime between the 13th and 18th centuries. The instrument’s development is closely linked to the griots, hereditary musicians and storytellers who served as custodians of Mandinka history, culture, and knowledge. Griots played the kora at important social gatherings, ceremonies, and royal courts, using it to accompany their epic narratives and genealogies. The kora’s sound became synonymous with the griots’ role as cultural guardians, and its music served to preserve and transmit the rich heritage of the Mandinka people.

The spread of the kora throughout West Africa can be attributed to the griots’ travels and migrations, as well as the expansion of the Mandinka empire. Over time, the instrument was adopted by other ethnic groups, including the Jola, Bambara, and Fula, each of whom developed their own unique playing styles and musical traditions. In the 20th and 21st centuries, the kora’s popularity has extended beyond West Africa, thanks to the efforts of musicians who have introduced the instrument to global audiences. Today, the kora is recognized as a symbol of West African musical excellence, and its sound continues to captivate listeners around the world.

Construction and Design

The kora’s construction is a testament to the ingenuity of West African instrument makers. The primary component of the instrument is a large calabash gourd, which serves as the resonator. The gourd is carefully selected for its size, shape, and resonance properties, and it is then cut and dried before being covered with cow skin. The cow skin is stretched tightly over the gourd and secured with wooden pegs or nails, creating a taut soundboard that amplifies the vibrations of the strings. The kora’s long neck, typically made from hardwood such as rosewood or mahogany, extends from the calabash and provides a stable platform for the strings. The neck is often decorated with intricate carvings, reflecting the artistry and craftsmanship of the instrument maker. The kora’s 21 strings are arranged in two parallel rows, running along either side of the bridge. Traditionally, these strings were made from thin strips of antelope skin, but modern koras often use nylon or harp strings. The bridge, a crucial element in the kora’s design, is typically made from hardwood and features notches or grooves to hold the strings in place. The bridge’s shape and height contribute to the kora’s distinctive sound and playing characteristics. Tuning pegs, located along the neck, allow the musician to adjust the tension of the strings and achieve the desired pitch. The overall design of the kora is a harmonious blend of form and function, with each component contributing to the instrument’s unique sound and visual appeal.

Types of Kora

While the basic design of the kora remains consistent, there are subtle variations in size, shape, and string arrangement that can be observed across different regions and among different ethnic groups. For instance, the size of the calabash resonator can vary, with larger gourds producing a deeper, more resonant sound. The length and shape of the neck can also differ, affecting the instrument’s overall scale and playing characteristics. The number of strings can also vary, though 21 strings is the most common configuration. Some regional variations may have less or more strings. Additionally, the materials used in the construction of the kora can vary depending on local resources and traditions. For example, some koras may feature decorative elements made from ivory, bone, or metal, while others may be adorned with intricate beadwork or leatherwork. The style of carving and ornamentation on the neck and other parts of the kora can also reflect the cultural identity of the instrument maker and the region in which it was made.

In contemporary music, the kora has undergone further modifications and adaptations to suit different musical styles and performance contexts. Electric koras, for example, have been developed to amplify the instrument’s sound and allow for greater flexibility in live performances. These electric koras often feature built-in pickups and preamps, allowing musicians to connect the instrument to amplifiers and effects processors. The development of electric koras has expanded the instrument’s sonic possibilities and made it more accessible to musicians working in genres such as jazz, fusion, and world music.

Characteristics of the Kora

The kora’s sound is characterized by its rich, resonant tone, its wide dynamic range, and its ability to produce both melodic and rhythmic textures. The instrument’s 21 strings allow for a wide range of pitches and harmonies, while its double-bridge design enables the musician to play both melodic lines and rhythmic patterns simultaneously. The kora’s sound is often described as being both soothing and uplifting, with a quality that is both earthy and ethereal. The instrument’s ability to evoke a range of emotions and moods has made it a popular choice for both traditional and contemporary music. The playing technique of the kora is highly specialized, requiring years of dedicated practice to master. Kora players typically use their thumbs and index fingers to pluck the strings, creating a rhythmic and melodic interplay between the two hands. The left hand is primarily responsible for playing the bass lines and rhythmic patterns, while the right hand focuses on the melodic lines and harmonies. The kora’s tuning system is also unique, with the strings arranged in a diatonic scale that allows for a wide range of melodic and harmonic possibilities. The specific tuning of the kora can vary depending on the region and the musical style being played.

The kora’s music is often characterized by its cyclical and repetitive nature, with melodic and rhythmic patterns that evolve and transform over time. This cyclical approach to music-making is deeply rooted in West African musical traditions and reflects the region’s emphasis on improvisation and variation. The kora’s music is also often characterized by its call-and-response patterns, with the musician alternating between melodic phrases and rhythmic interludes. This call-and-response technique creates a sense of dialogue and interaction between the musician and the audience, fostering a communal and participatory musical experience. The kora’s versatility has made it a popular choice for a wide range of musical genres, from traditional Mandinka music to contemporary jazz, fusion, and world music. Kora players have collaborated with musicians from diverse cultural backgrounds, creating innovative and cross-cultural musical fusions. The kora’s sound has also been featured in film soundtracks, television commercials, and other media, further expanding its reach and influence. The instrument’s enduring appeal lies in its ability to connect with audiences on a deep emotional level, transcending cultural boundaries and linguistic barriers.

Playing Techniques and Sound Modifications

The kora, a 21-string bridge-harp from West Africa, primarily associated with the Mandinka people, is played with a unique combination of plucking and finger techniques. The player typically sits with the instrument held vertically, resting on the lap. The thumbs of both hands are used to pluck the strings of the lower register, while the index fingers handle the higher notes. This bi-manual dexterity allows for intricate melodic lines and rhythmic patterns. The strings, traditionally made of antelope skin but now often of nylon, are arranged in two parallel rows, one on each side of the notched bridge. The bridge, a significant component, is perpendicular to the soundboard and acts as a fulcrum, transmitting string vibrations. The player’s thumbs and index fingers move independently, creating a complex interplay of melodic and harmonic layers. This polyphonic nature is a hallmark of kora music. A crucial aspect of kora playing is the use of the left thumb to create a bass ostinato, a repeating rhythmic and melodic figure that provides the foundation for the piece. The right hand then weaves intricate melodies and counter-melodies around this base. The flexibility of the kora allows for a wide range of musical expressions, from slow, contemplative melodies to fast, rhythmic dance pieces. Sound modifications are achieved through several techniques. The player can alter the tone and volume by varying the plucking intensity and the position of the fingers on the string. Muting the strings with the palm of the hand creates percussive effects, adding rhythmic texture. Vibrato, a subtle wavering of the pitch, is achieved by slightly bending the strings. The player can also adjust the tuning pegs, located along the neck of the instrument, to fine-tune the pitch of individual strings. This allows for subtle variations in tuning, adding color and depth to the sound. The bridge itself can be adjusted, sometimes by sliding small pieces of wood underneath, to alter the overall tone and resonance of the instrument. In some cases, players may use a small metal ring, called a “nyenyemo,” worn on the thumb, to create a metallic timbre when striking the strings. The resonating gourd, or calabash, which forms the body of the kora, also plays a critical role in shaping the sound. Its size and shape influence the volume and tonal qualities. Some players may even place objects inside the gourd to alter the resonance. The kora’s sound, therefore, is a product of its design and the player’s skillful manipulation of its strings and body.

Applications in Music

The kora’s versatility has led to its application in a wide range of musical contexts. Traditionally, it is central to the music of the Mandinka griots, hereditary musicians and oral historians who preserve and transmit cultural knowledge through song and storytelling. Griots use the kora to accompany their narratives, providing a musical backdrop that enhances the emotional impact of their words. In this context, the kora is not merely a musical instrument but a vital tool for cultural preservation. Beyond its traditional role, the kora has found a place in contemporary music, both within West Africa and internationally. It is frequently used in fusion music, blending traditional Mandinka melodies with genres such as jazz, blues, and classical music. The kora’s unique sound and melodic capabilities have made it a popular choice for composers and musicians seeking to explore new sonic landscapes. In West African popular music, the kora is often incorporated into modern arrangements, adding a touch of traditional flavor to contemporary songs. It is also used in film soundtracks, creating evocative and atmospheric soundscapes. The kora’s ability to express a wide range of emotions makes it suitable for various dramatic and narrative contexts. In classical music, composers have written pieces that feature the kora as a solo instrument or in ensemble settings. Its delicate and intricate sound has been successfully integrated into chamber music and orchestral works. The kora is also used in world music festivals and concerts, where it showcases the rich musical heritage of West Africa to a global audience. Its presence in these settings has helped to raise awareness of Mandinka culture and music. The instrument is also used in therapeutic settings, where its calming and meditative qualities are believed to promote relaxation and well-being. Its gentle melodies and soothing harmonies can create a tranquil atmosphere, making it a valuable tool for stress reduction and emotional healing. The kora’s versatility extends to educational settings, where it is used to teach students about West African music and culture. Its unique design and playing techniques provide a fascinating subject for study, fostering an appreciation for diverse musical traditions.

Most Influential Players

The kora’s rich history is filled with influential players who have shaped its development and popularization. Among the most celebrated is Toumani Diabaté, a Malian kora player renowned for his virtuosic technique and innovative approach to the instrument. He has collaborated with musicians from various genres, including jazz, blues, and classical music, bringing the kora to a wider audience. His albums, such as “New Ancient Strings” with Ballaké Sissoko, and “The Mandé Variations,” are considered masterpieces of kora music. Another influential figure is Sidiki Diabaté, Toumani’s father, who was also a highly respected kora player. He played a significant role in preserving and promoting traditional Mandinka music. Jali Musa Jawara, a Gambian kora player, is another important figure. He was known for his powerful voice and his ability to tell stories through his music. His performances were characterized by their emotional depth and cultural richness. Mory Kanté, a Guinean musician, gained international recognition for his use of the kora in popular music. His hit song “Yéké Yéké” brought the kora to a global audience, showcasing its versatility and appeal. Lamine Sissoko, a Senegalese kora player, is known for his innovative playing style and his ability to blend traditional Mandinka music with contemporary influences. He has collaborated with musicians from various genres, creating a unique and dynamic sound. Ballaké Sissoko, another Malian kora player, is renowned for his delicate and intricate playing style. His collaborations with Vincent Segal, a French cellist, have produced critically acclaimed albums that blend kora and cello music. These players, among others, have contributed to the kora’s evolution, pushing its boundaries and expanding its reach. Their virtuosity, creativity, and dedication to preserving and promoting Mandinka music have made them influential figures in the world of kora playing.

Maintenance and Care

Maintaining the kora requires careful attention to its delicate components. The gourd resonator, or calabash, is particularly vulnerable to damage. It should be kept in a dry, well-ventilated environment to prevent cracking or warping. Exposure to extreme temperatures or humidity can also cause damage. The strings, traditionally made of antelope skin but now often of nylon, need to be regularly checked for wear and tear. Broken or frayed strings should be replaced immediately to maintain the instrument’s sound quality and prevent further damage. The bridge, which transmits string vibrations to the soundboard, should be kept clean and free of debris. Dust and dirt can interfere with its function and affect the instrument’s tone. The tuning pegs, which adjust the pitch of the strings, should be lubricated periodically to ensure smooth operation. This prevents them from becoming stuck or difficult to turn. The neck of the kora, which supports the strings and tuning pegs, should be inspected regularly for cracks or damage. Any signs of damage should be addressed promptly to prevent further deterioration. The kora should be stored in a protective case when not in use. This protects it from dust, dirt, and physical damage. The case should be padded to cushion the instrument and prevent it from moving during transport. Regular cleaning is essential for maintaining the kora’s appearance and sound quality. A soft cloth should be used to wipe down the gourd, neck, and bridge. Avoid using harsh chemicals or abrasive cleaners, as they can damage the instrument’s finish. The strings can be cleaned with a soft cloth or a specialized string cleaner. This removes dirt and oils that can affect their tone and longevity. The kora should be tuned regularly to maintain its pitch and sound quality. Tuning can be done using a chromatic tuner or by ear. Proper maintenance and care will ensure that the kora remains in good condition and continues to produce its beautiful sound for many years.

Cultural Significance

The kora holds profound cultural significance in West Africa, particularly among the Mandinka people. It is deeply intertwined with the griot tradition, a hereditary caste of musicians and oral historians who preserve and transmit cultural knowledge through song and storytelling. The kora is not merely a musical instrument but a vital tool for preserving and transmitting history, genealogy, and cultural values. Griots use the kora to accompany their narratives, providing a musical backdrop that enhances the emotional impact of their words. The kora’s music is often used to celebrate important events, such as weddings, naming ceremonies, and religious festivals. It is also used to honor ancestors and commemorate historical figures. The kora’s sound is considered to be sacred, and its music is believed to have the power to heal and inspire. The instrument is often associated with spiritual and mystical beliefs. The kora is a symbol of Mandinka identity and cultural heritage. Its music is a source of pride and cultural expression.

The instrument’s design and playing techniques reflect the ingenuity and artistry of the Mandinka people. The kora’s cultural significance extends beyond the Mandinka people, as it is also embraced by other ethnic groups in West Africa. Its music is enjoyed and appreciated by people of all backgrounds. The kora has become an ambassador of West African culture, showcasing its rich musical heritage to a global audience. Its presence in international music festivals and concerts has helped to raise awareness of Mandinka culture and music.

FAQ

What are the main characteristics of the Kora?

The Kora is a 21-string West African harp-lute with a large calabash resonator covered in cowhide. It produces a melodic, harp-like sound and is played with both hands using thumb and index fingers. The instrument is traditionally used in griot storytelling and praise singing. Its tuning and string arrangements vary by region and musician.

What materials are used in the construction of the Kora?

The Kora is made from a large calabash gourd cut in half, covered with cowhide to form a resonator. A long wooden neck extends through the gourd, supporting 21 nylon or gut strings attached to leather tuning rings. The bridge is traditionally made of wood, allowing for fine tonal adjustments. These materials contribute to the Kora's distinctive sound.

How is the Kora used in traditional and modern music?

Traditionally, the Kora is played by griots (oral historians) for storytelling, ceremonies, and praise singing. It remains central in Manding music, especially in Mali, Senegal, and Guinea. In modern times, it is incorporated into jazz, blues, and fusion genres, expanding its global reach. Many contemporary musicians collaborate with Kora players to blend cultures.

Links

Links

References

Other Instrument

Categories