Mandolin

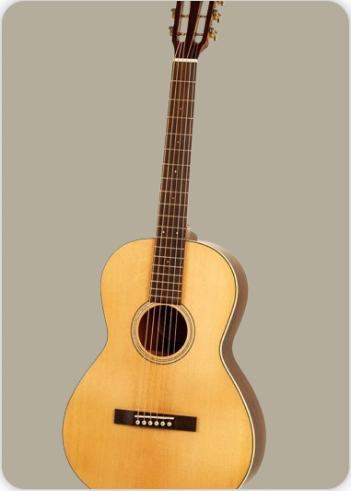

Plucked Instruments

Europe

Between 1001 and 1900 AD

Video

The mandolin is a small, stringed musical instrument belonging to the lute family, renowned for its bright, resonant sound and distinctive shape. Typically, a mandolin features a hollow wooden body, a short neck, and a flat or slightly arched fingerboard fitted with metal frets. The instrument’s most recognizable characteristic is its four courses of doubled strings—usually eight in total—tuned in unison, which are plucked or strummed with a plectrum. This string arrangement is most commonly tuned in intervals of perfect fifths, mirroring the tuning of a violin (G-D-A-E), which gives the mandolin its soprano voice within its instrumental family. The body of the mandolin can vary in shape, with the traditional Italian models exhibiting a deep, bowl-shaped back made from strips of wood, while modern variants may have a flat or arched back, similar to a guitar. The soundboard, or top, is typically constructed from spruce, and the back and sides from maple or other hardwoods, contributing to the instrument’s projection and tonal clarity.

Type of Instrument

The mandolin is classified as a chordophone, a category of musical instruments that produce sound primarily through the vibration of stretched strings. More specifically, it is a plucked string instrument, or plectrum instrument, given that it is typically played with a pick rather than with the fingers. Within the Hornbostel–Sachs system, which categorizes instruments based on their method of sound production, the mandolin is identified as a “necked bowl lute” or “necked box lute,” depending on its body shape. The Neapolitan mandolin, with its characteristic bowl back, is classified as 321.321-6, while the flat-backed variant is 321.322-6. Despite occasional confusion, the mandolin is not an aerophone, as it does not produce sound by vibrating a column of air; its sound comes exclusively from the vibration of its strings, which are amplified by the resonating body. The mandolin is the soprano member of its family, which also includes the mandola (alto), octave mandolin (tenor), mandocello (baritone), and mandobass (bass), each tuned to different registers but sharing similar construction and playing techniques. This family structure allows for ensemble playing, with each instrument contributing a unique voice to the overall texture. The mandolin’s role as a chordophone places it within a lineage of stringed instruments that have been central to musical traditions across the world, and its evolution reflects both technological advancements and changing musical tastes.

History of the Mandolin

The mandolin’s origins trace back to the rich tapestry of European stringed instruments, with its earliest ancestors emerging in Italy during the 17th and 18th centuries. The instrument evolved from the mandore and mandola, themselves descendants of the ancient lute, which had been a staple of European music since the Middle Ages. The mandore, a small lute with gut strings, was prevalent in the 14th and 15th centuries and gradually gave rise to a variety of regional instruments, including the mandola and, eventually, the mandolin. By the early 18th century, the mandolino—a small, six-stringed instrument played with a feather quill or plectrum—had become popular in Naples and other Italian cities. The Neapolitan mandolin, which emerged around the mid-18th century, is widely regarded as the prototype of the modern mandolin. This instrument featured four courses of paired metal strings, a bowl-shaped back, and a tuning system that mirrored the violin, making it accessible to violinists and facilitating its adoption in classical music circles.

The mandolin’s popularity quickly spread beyond Italy, finding enthusiastic audiences across Europe, particularly in France and Germany. Renowned luthiers such as the Vinaccia family in Naples and the Embergher family in Rome played pivotal roles in refining the instrument’s design and construction, introducing innovations that enhanced its playability and tonal qualities. The mandolin’s inclusion in the works of celebrated composers like Antonio Vivaldi, who wrote a concerto for the instrument, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who featured it in his opera “Don Giovanni,” further cemented its status as a legitimate and expressive voice in classical music. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the mandolin experienced a “Golden Age,” marked by the formation of mandolin orchestras and widespread popularity in both Europe and the Americas. During this period, the instrument’s repertoire expanded to include both classical and folk music, and its construction evolved to accommodate new playing styles and ensemble settings.

The 20th century saw the mandolin’s adaptation to a variety of musical genres, including bluegrass, jazz, and popular music, particularly in the United States. American luthiers such as Orville Gibson and Lloyd Loar introduced the flat-backed, arched-top mandolin, which became the standard for bluegrass and other contemporary styles. Despite fluctuations in popularity, the mandolin has endured as a beloved and versatile instrument, celebrated for its distinctive sound and rich cultural heritage. Its journey from the courts and salons of Baroque Italy to the stages of modern concert halls and folk festivals is a testament to its enduring appeal and adaptability.

Construction and Physical Structure

The construction of the mandolin is a testament to the ingenuity and craftsmanship of luthiers who have refined the instrument over centuries. At its core, the mandolin consists of a resonating body, a neck, a fingerboard, and a headstock fitted with tuning machines. The traditional Neapolitan mandolin features a deep, bowl-shaped back constructed from numerous narrow strips of hardwood, typically maple or rosewood, meticulously glued together to form a rounded shell. This bowl back not only contributes to the instrument’s distinctive appearance but also enhances its projection and tonal warmth. The soundboard, or top, is usually made from spruce, prized for its strength-to-weight ratio and its ability to transmit vibrations efficiently. The top is often slightly arched and may feature decorative inlays around the oval or round sound hole, which is sometimes protected by a shell or plastic plate to prevent damage from the plectrum. The neck of the mandolin is relatively short and is fitted with a flat or gently radiused fingerboard made from ebony or rosewood. Metal frets are embedded along the fingerboard, allowing for precise intonation and ease of play. The neck is attached to the body at a slight angle, and the headstock at the end of the neck houses the tuning machines, which are typically arranged in two sets of four. The strings, usually made of steel or bronze, are anchored at the tailpiece, pass over a floating bridge, and are wound onto the tuning machines at the headstock. The floating bridge, made from ebony or another hardwood, is not glued to the soundboard but is held in place by the downward pressure of the strings. This design allows for easy adjustment of string height and intonation.

Modern mandolins may feature flat or arched backs, following the innovations of American luthiers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The flat-backed mandolin, with its simpler construction and lighter weight, became popular in the United States and is now the standard for bluegrass and other contemporary genres. Some mandolins are equipped with internal or external pickups for amplification, while others may incorporate resonator plates or banjo-like bodies to increase volume. Despite these variations, the essential elements of the mandolin’s construction—paired strings, a floating bridge, and a resonant wooden body—remain consistent across its many forms.

Types of Mandolin

The mandolin family encompasses a variety of instruments, each with its own unique characteristics and historical significance. The most prominent types include the Neapolitan (bowl-back) mandolin, the flat-backed mandolin, and several related instruments that extend the range of the family. The Neapolitan mandolin, also known as the bowl-back or “tater bug” mandolin, is the archetypal Italian model, distinguished by its deep, rounded back and bright, penetrating tone. This type of mandolin is most closely associated with classical and traditional Italian music and remains popular among aficionados of historical performance. The Roman mandolin, developed in Rome and favored by professional players, features a similar bowl-back design but often incorporates subtle differences in construction and ornamentation. The flat-backed mandolin, pioneered by American luthiers such as Orville Gibson, features a shallower, guitar-like body with a flat or slightly arched back and top. This design produces a louder, more focused sound and is the standard in bluegrass, folk, and popular music. Variants of the flat-backed mandolin include the A-style (teardrop-shaped) and F-style (with decorative scrolls and points), each offering distinct aesthetic and tonal qualities.

Beyond the standard mandolin, the family includes several related instruments, each tuned to a different register. The mandola, larger than the mandolin, is tuned a fifth lower and serves as the alto voice in mandolin ensembles. The octave mandolin, as its name suggests, is tuned an octave below the mandolin and provides a rich, resonant tenor sound. The mandocello, even larger, is tuned a fifth below the mandola and serves as the baritone or bass voice. The mandobass, a rare and oversized member of the family, covers the lowest register and is typically used in mandolin orchestras. Other notable types include the resonator mandolin, which incorporates a metal resonator to increase volume, and the electric mandolin, equipped with pickups for amplification in contemporary music settings. Hybrid instruments, such as the mandolin-banjo, combine elements of both instruments to achieve unique tonal effects.

Characteristics of the Mandolin

The mandolin is celebrated for its distinctive sound, versatility, and expressive capabilities. Its paired strings, when plucked with a plectrum, produce a bright, clear tone with a rapid decay, making the instrument ideal for both melodic lines and rhythmic accompaniment. The use of tremolo—a technique involving the rapid alternation of the plectrum across the paired strings—allows players to sustain notes and create a shimmering, continuous sound that is emblematic of mandolin music. The instrument’s high register and agile response make it well-suited to fast, intricate passages, as well as lyrical melodies. The mandolin’s compact size and lightweight construction contribute to its portability and ease of play, making it accessible to musicians of all ages and skill levels. Its tuning in fifths, identical to the violin, facilitates the transfer of skills between the two instruments and allows for a wide range of musical expression. The mandolin’s versatility is further enhanced by its ability to blend seamlessly with other instruments, whether in solo, chamber, or orchestral settings.

In terms of repertoire, the mandolin boasts a rich and varied tradition, encompassing classical concertos, folk tunes, bluegrass breakdowns, and jazz improvisations. Its adaptability has ensured its continued relevance across centuries and continents, from the salons of Baroque Europe to the stages of modern music festivals. The instrument’s enduring popularity is a testament to its unique voice, expressive potential, and the artistry of the musicians and luthiers who have shaped its evolution. The mandolin’s construction, history, and musical characteristics combine to create an instrument of remarkable beauty and versatility, cherished by players and audiences alike for its bright sound, expressive range, and rich cultural heritage.

Playing Techniques and Sound Modifications

Mastering the mandolin involves a blend of precise technique, rhythmic control, and expressive ornamentation. The instrument is typically played with a pick, which is held at a slight angle to the strings to produce a clear, ringing tone. The right hand is responsible for both strumming chords and picking out melodies, alternating between upstrokes and downstrokes to maintain a consistent rhythm. Strumming is often used for chordal accompaniment, while fingerpicking or flatpicking techniques allow for intricate melodic lines. A key aspect of mandolin playing is the use of tremolo, a rapid repetition of a single note achieved by quickly alternating the pick direction. This technique creates a sustained sound that compensates for the instrument’s naturally short sustain. Other common ornamentations include hammer-ons, pull-offs, slides, and double stops. Hammer-ons and pull-offs allow for smooth transitions between notes, while slides add expressive glides up or down the fretboard. Double stops, where two notes are played simultaneously, enrich the harmonic texture.

Players often experiment with alternate tunings or use a capo to modify the instrument’s tonal range. The mandolin is traditionally tuned in fifths (G-D-A-E), similar to a violin, but alternate tunings can create new sonic possibilities. The use of different picks—varying in thickness, material, and shape—also affects the instrument’s tone and attack. Left-hand technique is just as critical as right-hand dexterity. Accurate finger placement close to the fretwire ensures clear intonation and minimizes buzzing. The mandolin’s doubled strings require more finger pressure than single-stringed instruments, demanding both strength and precision from the player. Practicing scales, arpeggios, and chord shapes across the fretboard develops the agility needed for advanced playing.

Sound modifications can also be achieved through dynamic control, muting techniques, and varying the picking position relative to the bridge. Picking closer to the bridge produces a brighter, more percussive sound, while picking over the sound hole yields a warmer tone. Muting the strings with the palm or fingers can create staccato effects, adding rhythmic interest to performances.

Famous Compositions

The mandolin has inspired a diverse repertoire, from baroque concertos to contemporary folk tunes. One of the most celebrated classical works is Antonio Vivaldi’s “Concerto for Mandolin in C major, RV 425,” which showcases the instrument’s agility and expressive potential. Ludwig van Beethoven also composed for the mandolin, writing several pieces for mandolin and piano that highlight its lyrical qualities. In the realm of Italian folk music, the mandolin is central to the tarantella, a lively dance characterized by rapid tempos and intricate melodies. The instrument features prominently in Neapolitan songs such as “O Sole Mio” and “Funiculì, Funiculà,” where its bright, chiming sound evokes the spirit of southern Italy. Bluegrass and American folk music have also embraced the mandolin, with Bill Monroe’s “Blue Moon of Kentucky” standing as a seminal example. In jazz, the mandolin has found a voice through compositions like David Grisman’s “Dawg’s Rag,” blending swing rhythms with virtuosic improvisation.

Most Influential Players

The history of the mandolin is shaped by a lineage of virtuoso performers. In the classical tradition, Raffaele Calace is revered for his technical innovations and prolific output, composing hundreds of works for the instrument and elevating its status in chamber music. In the 20th century, Italian mandolinist Giuseppe Anedda gained international recognition for his performances and recordings, bringing classical mandolin music to a wider audience. In the United States, Bill Monroe is hailed as the “Father of Bluegrass,” revolutionizing the role of the mandolin in American roots music with his driving rhythms and inventive solos. David Grisman expanded the mandolin’s horizons by fusing bluegrass, jazz, and folk influences into a genre known as “Dawg music.” His collaborations with guitarist Jerry Garcia and violinist Stéphane Grappelli introduced the instrument to new audiences. Chris Thile, a contemporary virtuoso, has pushed the boundaries of mandolin performance with his work in the bands Nickel Creek and Punch Brothers, as well as his solo interpretations of Bach and modern composers. Other influential players include Carlo Aonzo, known for his classical interpretations and educational work, and Caterina Lichtenberg, a leading figure in both classical and contemporary mandolin performance.

Historical Performances or Concerts

Throughout its history, the mandolin has graced the stages of prestigious concert halls and folk festivals alike. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, mandolin orchestras flourished across Europe and the Americas, performing arrangements of popular and classical works. These ensembles, often comprising dozens of players, showcased the instrument’s versatility and communal appeal. One landmark performance was the debut of Vivaldi’s Mandolin Concerto in Venice, which demonstrated the instrument’s potential as a solo voice within the orchestral setting. In the United States, Bill Monroe’s appearances at the Grand Ole Opry in the 1940s cemented the mandolin’s place in country and bluegrass music, influencing generations of musicians.

More recently, Chris Thile’s performances at Carnegie Hall and his tenure as host of the radio program “Live from Here” have brought the mandolin to contemporary audiences, blending classical, folk, and popular repertoire. International festivals such as the Festival Internacional de Mandolina in Italy and the Mandolin Symposium in the United States continue to celebrate the instrument’s rich heritage and evolving artistry.

Maintenance and Care

Proper maintenance is essential to preserve the mandolin’s playability and tone. The instrument should be stored in a hard case when not in use, protecting it from humidity, temperature fluctuations, and physical damage. Regular cleaning with a soft, dry cloth prevents the buildup of oils and debris on the strings and body. Strings should be changed periodically, as old strings lose their clarity and can break unexpectedly. When changing strings, it is important to replace them one at a time to maintain tension on the bridge and neck. Tuning should be done carefully, as the high tension of mandolin strings can lead to breakage if tightened too quickly. The fretboard can be cleaned with a slightly damp cloth, and occasional application of lemon oil helps prevent drying and cracking. The bridge and nut should be checked for proper alignment, as shifts can affect intonation and action. If the mandolin develops buzzing or playability issues, a professional luthier can adjust the truss rod, bridge height, or nut slots as needed.

Humidity control is crucial, especially for wooden instruments. Using a case humidifier during dry seasons helps prevent cracks and warping. Avoid exposing the mandolin to direct sunlight or extreme temperatures, as these conditions can damage the finish and structural integrity.

Interesting Facts and Cultural Significance

The mandolin’s origins trace back to the lute family, with early forms appearing in Italy during the 17th and 18th centuries. Its distinctive bowl-back design, known as the Neapolitan mandolin, became synonymous with Italian folk and classical music. Over time, flat-backed models emerged, particularly in the United States, where they became popular in bluegrass and folk genres. The instrument’s bright, shimmering sound has made it a symbol of romance and festivity in Italian culture. It is often depicted in art and literature as an accompaniment to serenades and courtship rituals. The mandolin’s portability and expressive range have contributed to its enduring popularity, allowing it to adapt to diverse musical traditions around the world. Mandolin orchestras, once a fixture of community music-making in Europe and America, played a significant role in popularizing the instrument. These ensembles fostered a sense of camaraderie and provided opportunities for amateur musicians to perform together.

In contemporary music, the mandolin has experienced a resurgence, appearing in genres as varied as rock, pop, and world music. Its unique timbre adds color and texture to recordings by artists such as Led Zeppelin, R.E.M., and The Lumineers. The mandolin’s influence extends beyond music, shaping cultural identities and traditions. In Italy, it remains a cherished emblem of regional pride, celebrated in festivals and folk celebrations. In the United States, it is a cornerstone of bluegrass and Americana, connecting musicians and audiences across generations. The mandolin’s versatility, rich history, and expressive power continue to inspire musicians and listeners alike, ensuring its place as one of the world’s most beloved stringed instruments.

FAQ

What are the primary features of the Italian mandolin?

The Italian mandolin typically has eight strings in four pairs, a teardrop-shaped body, and is played with a plectrum. It produces bright, resonant tones. The bowl-back design enhances projection. Fretted fingerboards allow precise intonation.

How is the mandolin used in music today?

Mandolins are used in classical, folk, bluegrass, and world music genres. They provide melodic lines, rapid tremolo effects, and rhythmic accompaniment. In Italy, they feature prominently in traditional serenades. Modern mandolins also appear in film scores and fusion music.

What is the historical origin of the Italian mandolin?

The Italian mandolin evolved in the 17th and 18th centuries from earlier lute-like instruments. Naples became a major center for its development. Luthiers like Vinaccia shaped its modern form. It gained popularity in baroque and romantic musical settings.

Links

Links

References

Other Instrument

Categories