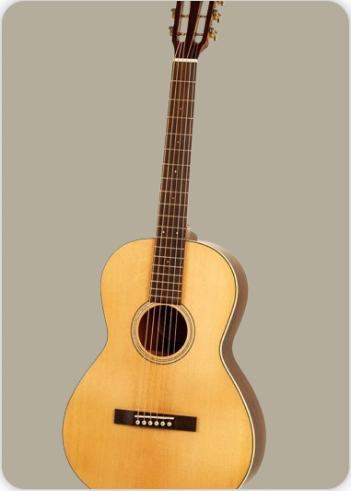

Recorder Flute

Woodwinds

Europe

Between 1001 and 1900 AD

The recorder is a cherished wind instrument with a deep history and a timeless appeal. Known for its clear, sweet tones and accessibility, the recorder has held a significant place in musical traditions across centuries. From its humble origins in the Middle Ages to its revival in modern times, the recorder has evolved in design and repertoire, making it a versatile and enduring part of musical culture. Its lightweight construction, expressive sound, and straightforward playability have made it a favorite in education, historical performances, and professional music ensembles.

History and Development

The recorder’s history is as rich and varied as the music it produces. First appearing in Europe during the 14th century, the instrument became a popular choice in both courtly and folk settings. By the Renaissance (15th–16th centuries), the recorder had taken on its familiar form, crafted primarily from wood and used extensively in ensemble performances. Its sound was valued for its ability to blend harmoniously with other instruments, and it often featured in lively dances and sacred music.

The Baroque era (17th to mid-18th century) marked the “Golden Age” of the recorder. It underwent significant refinements, including the adoption of a conical bore, the division of the body into three sections, and the addition of decorative turnings. These changes improved its tone and range, making it a favorite for composers like Handel, Telemann, and Vivaldi. The alto recorder in F became the predominant solo instrument of the time, showcasing the recorder’s expressive potential.

However, the Classical and Romantic periods saw the recorder decline in popularity, overshadowed by the transverse flute, which offered greater dynamic range and projection. For nearly a century, the recorder was largely absent from mainstream music until the 20th-century revival of early music. Musicians and educators rediscovered its charm, leading to a resurgence in its use for historical performances and education.

Construction and Types

The recorder is a beautifully simple yet highly effective instrument. Traditionally crafted from woods such as boxwood, maple, and pearwood, it is now also produced in plastic, offering a more affordable and durable option for students and amateurs. The recorder consists of three main parts: the head joint, where the player blows air into a whistle-like mouthpiece called a fipple; the body, which contains seven finger holes for pitch variation; and the foot joint, with an additional tone hole for extended range and control.

Recorders are made in a variety of sizes, each contributing to a distinct musical role. The sopranino, soprano (or descant), alto (or treble), tenor, and bass recorders form the primary family, with less common sizes like the great bass and contrabass adding depth to ensembles. Each size produces a different range of pitches, making the recorder versatile in both solo and group performances. The most common recorder in education is the soprano, while the alto remains a favorite for Baroque repertoire.

Cultural and Educational Significance

The recorder’s role in music history is as significant as its accessibility in modern times. During the Renaissance and Baroque periods, it was a mainstay in both sacred and secular music, appearing in courtly dances, church services, and chamber music. The instrument’s ability to convey both joy and solemnity made it indispensable in these settings.

In modern times, the recorder has become synonymous with music education. Its affordability, portability, and ease of use make it an ideal instrument for introducing students to the basics of music theory, fingering techniques, and ensemble playing. Educational programs across the world rely on the recorder to build foundational musical skills, fostering creativity and discipline in young learners. Beyond the classroom, the recorder is celebrated by amateur players and professional musicians alike, often featured in early music ensembles dedicated to historically informed performances.

Playing Technique

Producing sound on the recorder is deceptively simple but offers a wide range of expressive possibilities. The player blows into the mouthpiece, directing air through a narrow windway to create vibrations inside the instrument. Covering and uncovering the finger holes changes the length of the air column, producing different pitches. The thumbhole at the back adds further flexibility, allowing for overblowing to reach higher registers.

Articulation is a vital aspect of recorder playing. By varying the tonguing technique, players can achieve staccato notes, smooth legato phrases, or crisp accents, adding texture and character to their music. While the recorder’s range is typically just over two octaves, its dynamic capabilities and ability to blend make it a versatile instrument in both solo and ensemble settings.

The recorder’s enduring appeal lies in its adaptability. Whether played by a child learning their first melody or a seasoned professional performing a Baroque sonata, the recorder continues to inspire and delight audiences worldwide.

FAQ

What is the recorder made of?

Traditionally, recorders are made of wood like boxwood or maple, but modern versions are often crafted from plastic for durability and cost-effectiveness.

What are the different sizes of recorders?

The main sizes include Sopranino, Soprano (Descant), Alto (Treble), Tenor, Bass, and Great Bass. Each size is tuned to a specific pitch range.

Why is the recorder popular in music education?

The recorder is affordable, easy to play, and helps students learn basic music theory and fingering techniques, making it an ideal educational tool.

Who were famous composers that wrote for the recorder?

Famous Baroque composers like Handel, Telemann, and Vivaldi composed extensively for the recorder, showcasing its expressive potential.

What is the range of the recorder?

The recorder typically has a range of just over two octaves, varying slightly depending on the size and design of the instrument.

Links

Links

References

Other Instrument

Categories