Siku

Woodwinds

America

Between 0 and 1000 AD

Video

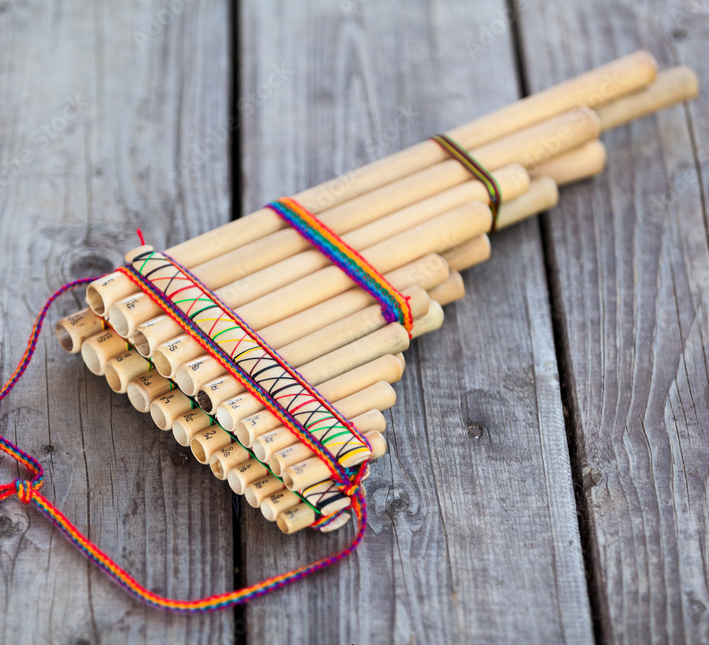

The siku, also known as the antara or panpipes, is a traditional Andean wind instrument composed of a series of cane tubes of varying lengths, bound together in one or two rows. Its distinctive sound, often described as melancholic and evocative, is a hallmark of Andean folk music. The instrument’s tone is produced by blowing across the open tops of the tubes, creating a resonant sound that varies in pitch depending on the length of each tube.

The siku is not merely a musical instrument; it holds deep cultural and spiritual significance for Andean peoples, representing a connection to their ancestors and the natural world. It is traditionally made from various types of cane, with meticulous attention to the selection and preparation of materials. The siku’s sound is used in a wide range of contexts, from ceremonial rituals and festive celebrations to personal expressions of emotion. The instrument’s versatility allows for a variety of musical expressions, from simple melodies to complex harmonic structures created by multiple siku players performing together. The construction and design of the siku, including the number and arrangement of tubes, contribute to its unique tonal qualities and cultural symbolism. The instrument is often played in ensembles, creating a rich tapestry of sound that reflects the communal nature of Andean music.

Type of Instrument

The siku is classified as a set of end-blown flutes, specifically a raft panpipe aerophone. Sound is produced by blowing across the open tops of the cane tubes, causing the air column within each tube to vibrate. This classification places it within a broad family of instruments that includes other panpipes found in various cultures around the world. However, the siku possesses unique characteristics that distinguish it from its counterparts. Notably, its construction from natural cane, its tuning system, and its cultural significance contribute to its distinctive sound and playing technique. The siku’s construction, involving multiple tubes of varying lengths, allows for the production of a wide range of pitches. The instrument’s design facilitates the creation of complex harmonies and melodies, particularly when played in ensembles. The method of producing sound, by blowing across the top of the tubes, is a simple yet effective technique that allows for subtle variations in tone and volume. The siku’s acoustic properties, influenced by the material and dimensions of the tubes, contribute to its characteristic sound.

History of the Siku

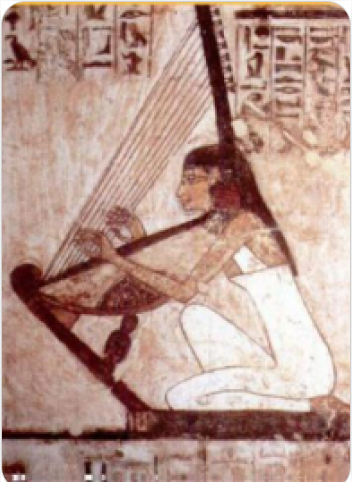

The siku’s history is deeply intertwined with the history of the Andean peoples, tracing its origins back to pre-Columbian times. Archaeological evidence suggests that panpipes have been used in the Andean region for thousands of years, with some of the earliest examples dating back to the pre-Inca cultures. The instrument reached its prominence during the Inca Empire, where it became a staple of ceremonial music and ritual performances. It was used in a wide range of musical contexts, including religious ceremonies, agricultural festivals, and social gatherings. The siku’s history is not simply a matter of chronological development, but also a reflection of its evolving cultural significance. Over the centuries, the siku underwent various modifications and adaptations, reflecting evolving musical tastes and technical innovations. In post-colonial times, the siku continued to be an important part of Andean folk music, serving as a symbol of cultural identity and resistance.

The instrument’s use in contemporary Andean music demonstrates its enduring relevance and adaptability. The history of the siku is a testament to the resilience and creativity of the Andean peoples, who have preserved and nurtured this unique musical tradition. The instrument’s use in modern renditions of classic works, and also in entirely new creations helps keep this traditional instrument a part of modern Andean culture.

Construction and Design

The construction and design of the siku are carefully crafted to optimize its sound and playing characteristics. Traditionally, the instrument is made from various types of cane, chosen for their density, flexibility, and tonal properties. The process of selecting and preparing the cane is a skilled craft, requiring meticulous attention to detail. The siku typically consists of two rows of cane tubes, known as ira and arca, which are bound together using natural fibers or other materials. The ira and arca are complementary rows, each containing a set of alternating notes that, when played together, create a complete scale. The number of tubes in each row can vary, depending on the size and tuning of the instrument. The length of each tube determines its pitch, with longer tubes producing lower notes and shorter tubes producing higher notes. The tubes are carefully cut and tuned to ensure accurate pitch and resonance. The siku’s design allows for the creation of complex harmonies and melodies, particularly when played in ensembles. The instrument’s construction reflects a deep understanding of acoustics and the properties of natural materials. The crafting of a siku is a process that connects the maker to their ancestors and the natural world. The materials used, and the construction methods used, are all vital to the final tone of the instrument.

Types of Siku

While the basic design of the siku remains consistent, there are various types that reflect regional differences and individual maker’s preferences. These variations often involve differences in size, tuning, and number of tubes. One common distinction is based on size, with some siku being larger and producing deeper, more resonant tones, while others are smaller and producing higher-pitched, more piercing notes. The tuning of the siku can also vary, depending on the specific musical tradition or cultural context. Some siku are tuned to specific scales or modes, reflecting the unique musical styles of different Andean communities. Another variation is based on the number of tubes in each row, with some siku having more or fewer tubes than others. The arrangement of the tubes can also vary, with some siku having a single row of tubes and others having two or more rows.

The types of cane used in construction can also vary, contributing to different tonal qualities and playing characteristics. The regional differences in siku design reflect the diversity and creativity of Andean musical traditions. Each type of siku possesses its own unique characteristics and cultural significance. The variety of siku available allows for diverse applications in musical and ceremonial contexts. While distinct types exist, each contributes to the overarching cultural signficance. The size of the instrument dictates the range of tones it can produce, and also the volume of the sound produced.

Characteristics of the Siku

The siku is known for its distinctive sound, which is characterized by its melancholic tone, resonant timbre, and expressive qualities. The instrument’s sound is often described as evocative and haunting, reflecting the deep connection between Andean peoples and their natural environment. The siku’s sound is produced by the vibration of the air column within the cane tubes, creating a complex waveform that is amplified and shaped by the instrument’s design. The instrument’s design, involving multiple tubes of varying lengths, allows for the production of a wide range of pitches and harmonies. The player can manipulate the instrument’s pitch and timbre through changes in breath control and embouchure. The siku’s sound is often used to express a range of emotions, from grief and lamentation to joy and celebration. The instrument’s ability to evoke such powerful emotions is a testament to its cultural significance. The siku’s characteristics are deeply rooted in Andean musical aesthetics, emphasizing the beauty of imperfection and the expressive power of timbre. The Siku is often played in large groups, with each player playing a part of the melody. This interlocking method of playing creates a complex and rich sound that is unique to the Siku. The sound produced by the Siku is often used in religious ceremonies, and other ritualistic performances. The sound of the Siku is an integral part of Andean culture, and is an instrument that has been played for thousands of years.

Playing Techniques and Sound Modifications

Playing the Siku involves a combination of breath control, lip placement, and coordination. The instrument is held horizontally, and the player directs a stream of air across the top edge of each tube, creating a vibrating air column. The varying lengths of the tubes produce different pitches, allowing the player to create melodies and harmonies. Skilled Siku players utilize a variety of techniques to achieve a wide range of sounds. Breath control is paramount, as subtle changes in air pressure can significantly alter the pitch and volume. The player must also coordinate their breath with the movement of the instrument, as each tube is played by moving the Siku across the lips. In many traditional Siku ensembles, players use a technique called “hocketing,” where different players alternate notes to create a continuous melody.

This technique requires precise timing and coordination, creating a complex and layered sound. Vibrato, achieved through subtle movements of the lips or the instrument, adds depth and richness to the sound. Glissando, or sliding between notes, is also used to create smooth, flowing melodies. Sound modifications can be achieved through partial covering of the tube openings, producing microtonal variations and subtle shadings in pitch. The player can also manipulate the angle and intensity of the air stream to create dynamic changes in volume and timbre. The use of different playing positions and techniques can also alter the instrument’s tone, adding further variety to the sound. The Siku’s design allows for a high degree of improvisation, enabling players to express their personal feelings and connect with their cultural heritage. The instrument’s unique sound and playing style make it a powerful tool for storytelling and emotional expression.

Applications in Music

The Siku’s primary applications lie within the rich tapestry of Andean traditional music. It has historically played a vital role in rituals, ceremonies, and social gatherings, where it contributed to the spiritual and cultural significance of these events. It is also found in genres such as huayno, where its distinctive sound adds a unique character to ensemble performances. In folk music, the Siku’s lyrical qualities are often employed to express emotions and tell stories. Its versatility has allowed it to adapt to various musical contexts, from solemn religious ceremonies to lively folk dances. In contemporary Andean music, the Siku has experienced a resurgence in popularity, finding its way into fusion genres and experimental compositions. Musicians are exploring new ways to incorporate the instrument’s unique sound into modern musical landscapes. In film soundtracks and theatrical productions, the Siku’s evocative melodies are used to create atmosphere and enhance storytelling, often evoking a sense of Andean culture and spirituality. Educational institutions use the Siku to teach students about Andean traditional music and culture, ensuring the preservation of this valuable musical heritage. The instrument also helps keep traditional practices alive, and allows for their transmission to future generations.

Most Influential Players

Identifying the most influential Siku players requires acknowledging both historical masters and contemporary performers who have contributed to the instrument’s legacy. In traditional Andean communities, skilled Siku players were highly respected for their mastery of the instrument and their deep understanding of musical traditions. Their expertise was often passed down through generations, preserving the intricate playing techniques and musical styles. In contemporary Andean music, musicians who are involved in preserving and revitalizing traditional music play very important roles.

Many of them also take part in educating others on their instruments. Recording technology has allowed contemporary Siku players to reach a wider audience, raising awareness of the instrument’s unique sound and cultural significance. Through performances, recordings, and educational programs, these musicians are ensuring that the Siku remains a vibrant part of Andean musical culture. Many instructors are also responsible for keeping the tradition alive. Groups like Los Kjarkas have helped to popularize the instrument to a global audience.

Maintenance and Care

The Siku, crafted from cane, requires careful maintenance to ensure its longevity and optimal performance. As a natural material, cane is susceptible to changes in humidity and temperature, which can lead to cracking or warping. To prevent damage, the Siku should be stored in a stable environment, away from direct sunlight and extreme temperature fluctuations. After playing, the instrument should be wiped clean with a soft cloth to remove moisture and debris. Regular cleaning of the tube openings is also essential to prevent blockages. Oiling the interior bore of the Siku can also help to condition the cane and prevent cracking. When the instrument is not in use, it is best to store it in a protective case. Should cracks or other damage occur, it is advisable to seek the assistance of a skilled instrument maker or repairer who specializes in Andean traditional instruments. Regular maintenance and proper care will help to preserve the Siku’s sound and ensure that it can continue to produce its beautiful melodies for many years.

Cultural Significance

The Siku’s cultural significance is deeply rooted in the history and traditions of the Andean region. As an instrument that has been used in rituals, ceremonies, and social gatherings for centuries, it embodies the spiritual and cultural values of the Andean people. Its sound is often associated with the natural world, evoking a sense of connection to the mountains, rivers, and landscapes of the Andes. The Siku also serves as a symbol of cultural identity, representing the artistic heritage of the indigenous communities.

In contemporary Andean society, the Siku plays a vital role in preserving and promoting traditional music. Its presence in educational institutions and cultural programs helps to ensure that younger generations are aware of their musical heritage. The instrument’s use in contemporary compositions and fusion genres demonstrates its enduring relevance and its ability to connect with audiences across cultures. By keeping this beautiful instrument and it’s history alive, future generations can enjoy the Siku.

FAQ

What materials are used to make the Siku?

The Siku is traditionally made from bamboo or cane tubes of varying lengths. The tubes are tied together using wool or synthetic cords. Modern versions may use PVC or metal for durability. The materials influence the instrument’s tone and resonance.

What are the main types of Siku?

The two main types of Siku are the Ira and Arka, which are played together in interlocking melodies. Variants include the Chuli (small), Malta (medium), and Sanka (large). Each type has a distinct pitch range and is used for different musical styles.

What are the cultural and musical applications of the Siku?

The Siku is integral to Andean folk music, particularly in festivals and ceremonies. It is played in ensembles to create rich, harmonized melodies. It is commonly heard in traditional dances and rural celebrations in Peru, Bolivia, and northern Argentina.

Links

Links

References

Other Instrument

Categories