Sitar

Plucked Instruments

Asia

Between 1001 and 1900 AD

Video

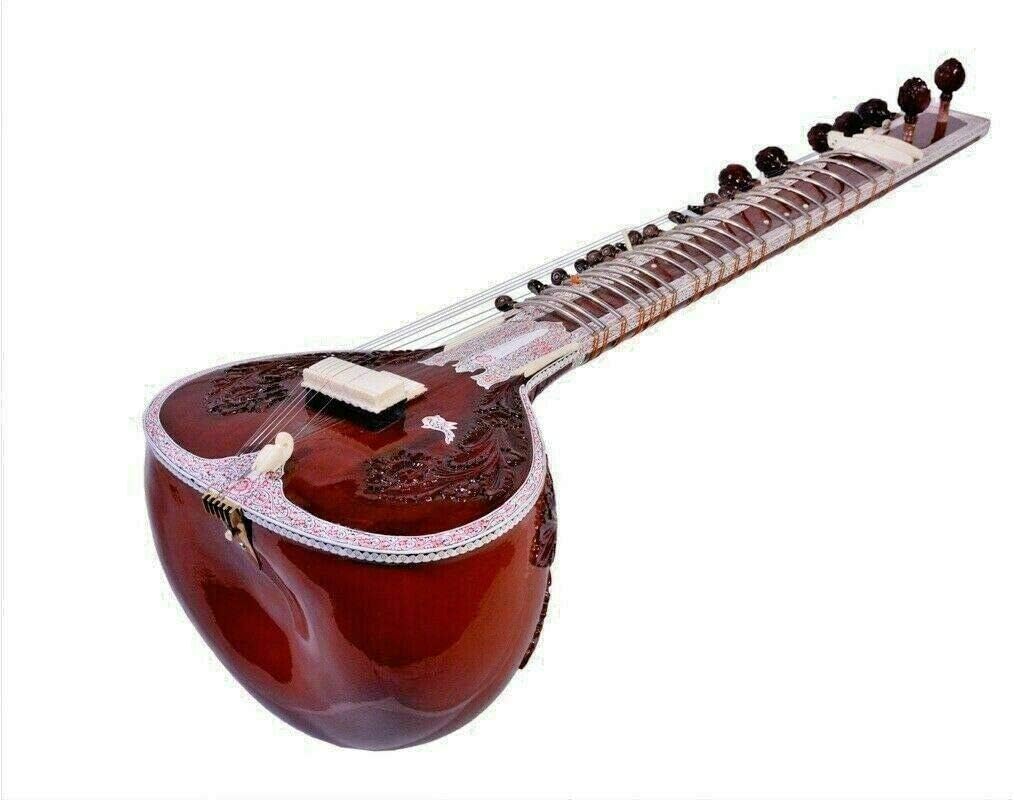

The sitar is one of the most iconic and recognizable musical instruments of Indian classical music, celebrated for its distinctive sound and elegant, elongated form. This plucked string instrument is primarily used in Hindustani classical music, which is the classical music tradition of northern India. The sitar is characterized by its long, hollow neck and a resonant, rounded gourd body that gives it a pear-like appearance. Typically measuring about four feet (1.2 meters) in length, the sitar is played while sitting on the floor, with the instrument held at an angle, resting on the player’s foot and balanced against the knee. Its unique construction and playing technique contribute to its rich, complex sound, which is instantly recognizable even to those unfamiliar with Indian music.

The sitar belongs to the family of chordophones, which are instruments that produce sound primarily by way of vibrating strings stretched between two points. More specifically, it is classified as a plucked string instrument, similar in some respects to the lute, guitar, or banjo, but with unique features that set it apart. The sitar is distinguished by its combination of main playing strings and sympathetic strings, as well as its movable frets and resonating gourd body.

History of the Sitar

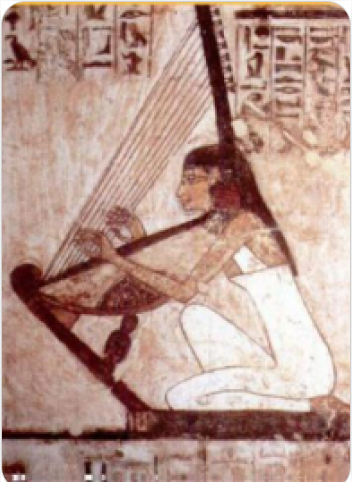

The sitar’s history is deeply intertwined with the cultural and musical evolution of the Indian subcontinent. Its origins can be traced back several centuries, with influences from both indigenous Indian instruments and those introduced from Central Asia. The sitar as it is known today began to take shape in the Indian subcontinent, particularly in the northern regions, during the medieval period. While the precise date of its invention is debated, most scholars agree that the sitar emerged sometime between the 13th and 18th centuries, evolving from earlier stringed instruments such as the veena and the Persian setar. The word “sitar” itself is derived from the Persian “seh-tar,” meaning “three strings,” which reflects the instrument’s early form. The arrival of Persian and Central Asian musical traditions in India, particularly during the Mughal era, played a significant role in shaping the sitar’s design and repertoire. The fusion of Indian and Persian musical elements led to the development of new instruments, playing techniques, and musical forms. The sitar’s adoption of sympathetic strings, movable frets, and a gourd resonator can be seen as a synthesis of these diverse influences.

By the 18th century, the sitar had become firmly established as a prominent instrument in the courts and musical circles of northern India. It was during this period that the instrument underwent significant refinement, with the addition of more strings, the development of the distinctive jawari bridge, and the standardization of its physical structure. The sitar’s popularity continued to grow throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, as it became a central instrument in the performance of Hindustani classical music. The sitar’s rise to international prominence can be largely attributed to the efforts of virtuoso musicians such as Ravi Shankar, Vilayat Khan, and Nikhil Banerjee, who introduced the instrument to audiences around the world. Ravi Shankar, in particular, played a pivotal role in popularizing the sitar in the West through his collaborations with Western musicians, performances at major music festivals, and recordings. The sitar’s distinctive sound captivated listeners and inspired a wave of cross-cultural musical experimentation, leading to its incorporation into popular music, jazz, and other genres.

Today, the sitar continues to be a vital and evolving instrument, cherished for its rich history, expressive capabilities, and enduring appeal. It remains a symbol of India’s musical heritage, celebrated both within the country and around the globe.

Construction and Physical Structure

The construction of the sitar is a meticulous and labor-intensive process, requiring skilled craftsmanship and an understanding of both acoustics and aesthetics. The instrument is composed of several key components, each of which contributes to its unique sound and playability. The main body of the sitar, known as the resonator or “tumba,” is typically made from a large, dried gourd. This gourd is carefully selected for its size, shape, and acoustic properties, as it serves as the primary sound chamber. The gourd is hollowed out and polished, then attached to the neck of the instrument. The neck, or “dandi,” is usually made from seasoned teak or tun wood, chosen for its strength, stability, and resonance. The neck is long and hollow, with a flat face onto which the frets are tied. The frets themselves are made from curved metal rods, which are tied to the neck with silk or nylon thread. These frets are movable, allowing the player to adjust their position to accommodate different ragas and tuning systems. The curved shape of the frets enables the player to bend notes and produce the characteristic gliding sound of the sitar.

The sitar’s strings are made from steel or brass, with the main playing strings being thicker and the sympathetic strings thinner. The main strings are anchored at one end to large tuning pegs, which protrude from the side of the head, while the sympathetic strings are wound around smaller pegs on the front. The strings pass over the bridge, which is typically made from bone, ivory, or synthetic materials. The bridge is flat and slightly angled, contributing to the sitar’s distinctive buzzing sound. Some sitars feature a secondary, smaller gourd attached to the top of the neck, known as the “chikari” or “tarafdar.” This additional resonator enhances the instrument’s volume and tonal richness, particularly in larger performance settings.

The sitar’s physical structure is both functional and decorative. The body and neck are often adorned with intricate inlays, carvings, and decorative motifs, reflecting the instrument’s status as both a musical tool and a work of art. The choice of materials, the quality of craftsmanship, and the attention to detail all play a role in determining the instrument’s sound quality and aesthetic appeal. The sitar’s design has evolved over time, with different schools and makers introducing variations in size, shape, and construction techniques. Despite these differences, the essential features of the sitar—its long neck, resonant gourd body, movable frets, and combination of main and sympathetic strings—have remained consistent, ensuring its distinctive sound and enduring popularity.

Types of Sitar

There are several types of sitar, each with its own unique characteristics and historical lineage. The two main types are the “Ravi Shankar style” and the “Vilayat Khan style,” named after the legendary musicians who popularized them. These styles differ in terms of construction, string arrangement, and playing technique.

The Ravi Shankar style sitar, also known as the “Kharaj Pancham” sitar, typically has 19 to 21 strings, including seven main playing strings and 13 to 15 sympathetic strings. This type of sitar is known for its deep, resonant sound and is often used for playing both melody and rhythm. The frets are usually larger and more widely spaced, allowing for greater flexibility in melodic ornamentation.

The Vilayat Khan style sitar, also known as the “Gandhar Pancham” sitar, usually has 17 to 19 strings, with six main playing strings and 11 to 13 sympathetic strings. This type of sitar is characterized by a lighter, more delicate sound and is often favored for its clarity and precision. The frets are smaller and closer together, facilitating rapid, intricate fingerwork.

In addition to these two main types, there are also variations in size, shape, and decoration, reflecting the preferences of individual makers and musicians. Some sitars are designed specifically for solo performance, while others are intended for accompaniment or ensemble playing. The choice of sitar often depends on the musician’s style, repertoire, and personal preference.

Characteristics of the Sitar

The sitar is renowned for its distinctive sound, which is both melodic and percussive, rich in overtones and capable of conveying a wide range of emotions. Its combination of main playing strings and sympathetic strings creates a complex, shimmering texture that is unique among stringed instruments. The use of movable frets allows for microtonal adjustments and intricate melodic ornamentation, while the resonant gourd body provides depth and warmth to the sound. One of the most striking characteristics of the sitar is its ability to produce sustained notes and expressive slides, known as “meend.” This technique involves pulling the string across the fret to create a smooth, continuous change in pitch, adding a vocal quality to the music. The sitar’s design also allows for rapid, virtuosic passages, making it well-suited to the improvisational and highly expressive nature of Indian classical music.

The sitar’s sound is further enhanced by the use of the jawari bridge, which creates a distinctive buzzing effect that adds complexity and richness to the tone. This buzzing sound is a defining feature of the sitar, contributing to its unique timbre and emotional impact. In addition to its musical characteristics, the sitar is also valued for its aesthetic beauty. The instrument is often adorned with intricate inlays, carvings, and decorative motifs, reflecting the artistic traditions of the regions in which it is made. The choice of materials, the quality of craftsmanship, and the attention to detail all contribute to the instrument’s visual appeal. The sitar’s versatility and expressive power have made it a favorite among musicians and audiences alike. Its ability to convey a wide range of emotions, from meditative calm to ecstatic joy, has ensured its enduring popularity and continued relevance in both traditional and contemporary music.

Playing Techniques and Sound Modifications

The sitar is renowned for its intricate playing techniques, which contribute to its expressive and evocative sound. Players sit cross-legged on the floor, resting the gourd resonator (tumba) on their foot and holding the neck at an upward diagonal. The right hand, adorned with a wire plectrum called a mizrab on the index finger, plucks the main strings, while the left hand manipulates the strings on the frets to produce melody and ornamentation. A unique aspect of sitar playing is the ability to pull the strings sideways while pressing them against the frets, allowing for the articulation of microtonal nuances and subtle ornaments that are characteristic of Indian classical music. Key techniques include meend, which is a smooth glide between notes achieved by pulling the string laterally across the fret. This technique is essential for conveying emotion and is a defining feature of the sitar’s sound. Gamak involves rapid oscillation between notes, creating a vibrato effect that adds depth and intensity. Krintan is a quick flick of the string, used to ornament specific notes, while murki consists of rapid, light flourishes that add excitement and complexity to a passage. Jhala, a fast-paced rhythmic strumming of the drone strings, is often used to build intensity towards the end of a performance.

The right hand employs both da (downstroke) and ra (upstroke) plucks, which are combined in various patterns to create complex rhythmic textures. Advanced players skillfully coordinate both hands to execute intricate improvisations, incorporating ornamentation, rapid note sequences, and dynamic variations in volume and timbre. The sympathetic strings, though not directly plucked, resonate in response to the main strings, enriching the instrument’s sound with shimmering overtones. Sound modifications are achieved through both technique and instrument setup. Adjusting the bridge, using different mizrabs, and tuning the sympathetic strings to specific ragas all influence the tonal color and resonance. Players may also experiment with string gauges and materials to produce brighter or mellower tones. The sitar’s construction, with its long, hollow neck and gourd resonator, amplifies these subtle variations, making it one of the most expressive stringed instruments in the world.

Famous Compositions

The sitar repertoire is deeply rooted in the tradition of ragas, each with its own mood, time of day, and emotional resonance. Some of the most celebrated sitar compositions are based on ragas such as Yaman, Bhairav, Bageshree, and Darbari Kanada. These compositions often begin with an alap, a slow, improvisational introduction that explores the raga’s melodic possibilities. This is followed by the jor, a section with a steady pulse, and the jhala, which features rapid, rhythmic strumming. Among the most famous sitar compositions are Ravi Shankar’s renditions of Raga Jog and Raga Kameshwari, which have become benchmarks in the instrument’s history. Vilayat Khan’s interpretations of Raga Shree and Raga Desh are also highly regarded for their emotional depth and technical brilliance. Nikhil Banerjee’s performances of Raga Malkauns and Raga Hemant are celebrated for their meditative quality and intricate improvisations. In the realm of fusion and popular music, the sitar has featured in iconic compositions such as “Within You Without You” by The Beatles, where George Harrison introduced the instrument to a global audience. Anoushka Shankar’s contemporary works blend traditional ragas with modern influences, resulting in compositions that appeal to diverse audiences while maintaining the essence of classical sitar music.

Most Influential Players

The sitar’s global recognition owes much to the artistry and innovation of its most influential players. Ravi Shankar is perhaps the most famous sitarist, credited with popularizing the instrument worldwide through his collaborations with Western musicians and performances at major festivals. His deep understanding of ragas, combined with his ability to communicate across cultures, made him a musical ambassador for India.

Vilayat Khan, another legendary figure, is known for his lyrical style and the development of the gayaki ang, or vocal style of sitar playing. His approach emphasized melodic expression and subtle ornamentation, influencing generations of musicians. Nikhil Banerjee, revered for his introspective and meditative performances, brought a spiritual dimension to sitar music, captivating audiences with his profound interpretations of ragas.

Anoushka Shankar, Ravi Shankar’s daughter, has continued the family legacy while forging her own path. Her innovative collaborations and genre-crossing projects have expanded the sitar’s reach, introducing it to new audiences and contexts. Shahid Parvez and Budhaditya Mukherjee are also highly respected for their technical mastery and contributions to the evolution of sitar music.

George Harrison, though not a classical sitarist, played a pivotal role in introducing the instrument to Western popular music, inspiring a wave of interest and experimentation that continues to this day.

Historical Performances or Concerts

The sitar has been featured in numerous landmark performances that have shaped its history and perception. One of the most significant was Ravi Shankar’s appearance at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, where his virtuosic performance captivated a Western audience and marked a turning point in the global appreciation of Indian classical music. His subsequent performances at Woodstock and the Concert for Bangladesh further solidified his status as a cultural icon. Vilayat Khan’s concerts at the All India Radio and the Sawai Gandharva Festival are remembered for their emotional intensity and technical brilliance. Nikhil Banerjee’s live recordings from the Sadarang Music Circle and his performances at the Calcutta Music Circle are treasured for their spiritual depth and improvisational mastery.

In recent years, Anoushka Shankar’s concerts at prestigious venues such as the Royal Albert Hall and Carnegie Hall have showcased the sitar’s versatility and continued relevance. Her collaborations with artists from various genres highlight the instrument’s adaptability and enduring appeal. The sitar has also played a prominent role in cross-cultural events, such as the collaboration between Ravi Shankar and Yehudi Menuhin, which brought together Indian and Western classical traditions in groundbreaking performances.

Maintenance and Care

Proper maintenance and care are essential to preserving the sitar’s unique sound and longevity. The instrument should be kept in a stable environment, away from extreme temperatures and humidity, which can cause the wood to warp or crack. Regular cleaning with a soft, dry cloth helps prevent dust and grime buildup on the body and strings. The strings, especially the main playing and sympathetic strings, should be checked regularly for signs of wear and replaced as needed. Tuning pegs and frets should be inspected for smooth operation, and any signs of loosening or damage should be addressed promptly. Applying a small amount of oil to the pegs can help maintain smooth tuning. The bridge, which is crucial for sound transmission, should be kept clean and properly positioned. Over time, the bridge may develop grooves from string contact; these should be smoothed out by a professional to prevent buzzing or loss of tone. The gourd resonator, being fragile, requires careful handling to avoid cracks or dents. When not in use, the sitar should be stored in a padded case to protect it from physical damage. If the instrument is to be transported, extra care should be taken to secure the delicate parts, especially the sympathetic strings and bridge.

Interesting Facts and Cultural Significance

The sitar holds a place of deep cultural significance in India and beyond. It is not only a symbol of classical music but also a bridge between cultures. The instrument’s origins can be traced back to the ancient veena, evolving over centuries to its present form during the Mughal era. Its name is derived from the Persian word “sehtar,” meaning “three strings,” though modern sitars typically have 18 to 21 strings. The sitar’s distinctive sound, characterized by its shimmering resonance and melodic richness, has made it a favorite for both traditional and experimental music. Its role in Indian classical music is central, often serving as the lead instrument in solo and ensemble performances. The sitar is also associated with spiritual and meditative practices, with its music believed to evoke specific emotions and states of mind. One of the most interesting aspects of the sitar is its ability to produce microtonal variations, allowing for the expression of subtle emotional nuances that are difficult to achieve on Western instruments. The sympathetic strings, which vibrate in response to the main strings, create a natural reverb effect that adds depth and complexity to the sound.

The sitar’s influence extends beyond classical music. It has been embraced by jazz, rock, and electronic musicians, contributing to the development of world music and fusion genres. The instrument’s appearance in popular culture, from Bollywood films to Western rock albums, has cemented its status as a global icon. In Indian society, learning the sitar is often seen as a mark of cultural refinement and artistic achievement. The instrument is featured in major festivals, religious ceremonies, and national celebrations, reflecting its enduring importance in the country’s cultural landscape.

Cultural Significance

The sitar is more than just a musical instrument; it is a cultural emblem that represents the artistic and spiritual heritage of India. Its music is closely linked to the concept of rasa, or aesthetic emotion, which is central to Indian art and philosophy. Each raga performed on the sitar is intended to evoke a specific mood or feeling, from joy and devotion to longing and tranquility. The instrument’s prominence in Indian classical music has made it a symbol of national identity, celebrated in literature, art, and cinema. Sitar music is often used to accompany dance, drama, and poetry, enhancing the emotional impact of these art forms. Internationally, the sitar has played a key role in fostering cross-cultural understanding and collaboration. Its adoption by Western musicians in the 1960s sparked a wave of interest in Indian music and philosophy, influencing the counterculture movement and shaping the sound of contemporary music.

The sitar continues to inspire new generations of musicians and listeners, serving as a testament to the power of music to transcend boundaries and connect people across cultures and traditions. Its legacy is preserved not only in concert halls and recordings but also in the hearts and minds of those who are moved by its timeless sound.

FAQ

What is the construction and material used in a Sitar?

A Sitar is primarily made from seasoned teak or tun wood with a resonating gourd made of dried pumpkin. It features a long, hollow neck and movable frets. The strings are metal, with sympathetic strings beneath the main ones. The instrument is finely decorated and carefully crafted for tonal quality.

What are the different types of Sitars?

There are mainly two types of Sitars: the Ravi Shankar style (with a deeper tone and more decorated structure) and the Vilayat Khan style (lighter, with a cleaner, more modern tone). Both have slight design and tonal variations and are used in Hindustani classical music.

What is the historical background of the Sitar?

The Sitar evolved in medieval India, likely in the 13th century, influenced by Persian instruments like the Setar. It became prominent in the Mughal era and was refined over centuries. It gained international recognition in the 20th century through maestros like Ravi Shankar.

Links

Links

References

Other Instrument

Categories