Tanpura

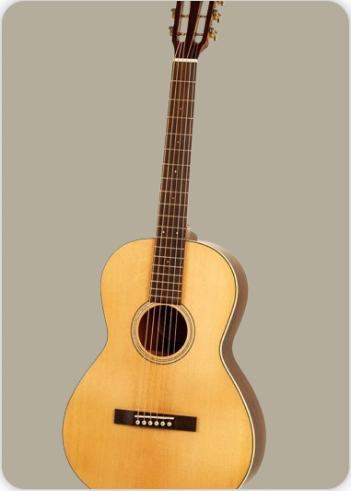

Plucked Instruments

Asia

Between 1001 and 1900 AD

Video

The tanpura, also known as tambura or tanpuri, is a long-necked, fretless string instrument that is fundamental to Indian classical music. Unlike melodic instruments, the tanpura does not produce a melody or rhythm but instead provides a continuous harmonic drone that serves as the sonic foundation for vocalists and instrumentalists. Its role is to create a sustained tonal reference, known as the adharaswara, which underpins the melodic framework of a raga. The instrument is typically played by gently plucking its strings in a regular, cyclic pattern, producing a rich tapestry of overtones and a resonant, meditative soundscape. The tanpura’s sonic character is distinguished by its overtone-rich timbre and the subtle, oscillating quality of its notes, which are achieved through its unique construction and tuning techniques.

Type of Instrument

The tanpura belongs to the family of chordophones, specifically the lute family. It is classified as a drone instrument because its primary function is to provide a continuous, unchanging harmonic support rather than to play melodies or rhythms. The tanpura is closely related in appearance to the sitar but is distinguished by its lack of frets and its exclusive use as a drone. It is plucked with the fingers, and its strings are tuned to the tonic and other key notes of the raga being performed. The instrument is integral to both Hindustani (North Indian) and Carnatic (South Indian) classical music traditions, though it is known by different names and exhibits some regional variations in construction and playing style.

History of the Tanpura

The origins of the tanpura can be traced back to ancient India, and it has long been a central element in the evolution of Indian classical music. The modern form of the tanpura is believed to have fully developed by the end of the 16th century, as evidenced by its depiction in Mughal miniature paintings. The instrument’s name is thought to derive from either the Sanskrit word “tana” (meaning a musical phrase) combined with “pura” (meaning full), or from the Persian word “tanbur,” which refers to a group of long-necked lutes from the Middle East. This etymological connection suggests a possible historical link between the tanpura and similar instruments from Persia and Central Asia, reflecting the cultural exchanges that shaped the musical landscape of the Indian subcontinent. Throughout history, the tanpura has played a vital role in the performance of Indian classical music, serving as the foundation for the development of ragas and the exploration of microtonal nuances.

It was commonly used in royal courts and temples, often adorned with intricate paintings and carvings that reflected the artistic sensibilities of the time. The instrument’s enduring significance is evident in its continued use in both traditional and contemporary music settings, as well as in the ongoing craftsmanship of tanpura makers, particularly in the town of Miraj in Maharashtra, which is renowned for producing high-quality instruments.

Construction and Physical Structure

The tanpura is characterized by its elongated, hollow neck and rounded resonating body, which together contribute to its distinctive sound. The instrument typically measures between 3 to 5 feet in length, with larger versions used by male vocalists and smaller ones by female vocalists or as accompaniment for certain instruments. The main components of the tanpura include:

-

The resonator or “tumba,” usually crafted from a large, dried gourd or, in some regions, from hollowed jackwood.

-

The soundboard or “tabli,” made from a thin piece of wood that amplifies the vibrations of the strings.

-

The neck joint or “gullu,” which connects the neck to the resonator.

-

The fingerboard or “patta,” a long, flat surface along which the strings run.

-

The neck or “dandi,” which supports the tuning pegs and provides structural integrity.

The tanpura generally has four metal strings, though some versions may have five or, rarely, six. The strings are anchored at the base of the instrument, stretched over a slightly curved, table-shaped bridge, and attached to tuning pegs at the top of the neck. The bridge is a critical feature, as its curvature and the placement of a small cotton thread between the strings and the bridge create the characteristic “jivari” or buzzing sound. This buzzing effect enhances the richness of the overtones and contributes to the instrument’s unique sonic texture.

Precision in tuning is achieved by adjusting the tension of the strings, the position of the cotton thread, and sometimes by inserting small beads or bits of wool. The tanpura is held vertically during performance, with the player seated behind it and gently plucking the strings in a continuous, cyclic motion.

Types of Tanpura

The tanpura comes in several variations, each tailored to specific musical contexts and preferences. The three principal styles are:

Miraj Style: Named after the town of Miraj in Maharashtra, this is the most widely recognized form of tanpura. It features a large, rounded gourd resonator and is favored for its deep, resonant sound. The Miraj style is commonly used in Hindustani classical music and is considered the standard for professional performance.

Tanjore Style: Originating from the Tanjore region in South India, this style is prevalent in Carnatic music. The Tanjore tanpura is typically made from jackwood and has a slightly different shape and construction compared to the Miraj style, resulting in a distinct tonal quality.

Tamburi or Tanpuri: This is a smaller version of the tanpura, often used to accompany instrumental soloists or as a portable alternative for vocalists. The tamburi retains the essential features of the larger instrument but produces a higher-pitched, more delicate drone.

In addition to these main types, there are numerous regional and folk variations, such as the box tanpura, burra katha vina, and the Sindhi dambooro, each reflecting local musical traditions and craftsmanship.

Characteristics of the Tanpura

The tanpura is distinguished by several unique characteristics that set it apart from other stringed instruments:

Drone Function: Its primary role is to provide a continuous, unchanging drone that serves as the tonal anchor for the performance. This drone is essential for establishing the pitch framework of the raga and for supporting the melodic improvisations of the soloist.

Overtone-Rich Sound: The tanpura’s construction and the use of the jivari technique produce a sound rich in harmonics and overtones. This creates a complex, shimmering sonic texture that enhances the depth and resonance of the music.

Fretless Design: The absence of frets allows the strings to vibrate freely along their entire length, contributing to the instrument’s fluid, oscillating notes and microtonal subtleties.

Tuning Flexibility: The tanpura can be tuned to different pitches and tonalities to match the requirements of various ragas and vocal ranges. Fine adjustments are made using the cotton thread and other tuning aids to achieve the desired tonal shade.

Aesthetic Appeal: Many tanpuras are adorned with decorative elements, including inlays, carvings, and paintings, reflecting the artistic heritage of their makers and the cultural significance of the instrument.

The tanpura’s unique combination of acoustic properties and aesthetic qualities makes it an indispensable component of Indian classical music, revered for its ability to create a serene and immersive sonic environment.

The Role of Tanpura in Indian Classical Music

In both Hindustani and Carnatic traditions, the tanpura is considered the foundation of the musical ensemble. Its drone establishes the tonal center and provides a reference for intonation, allowing the soloist to explore the full expressive range of the raga. The continuous, unbroken sound of the tanpura creates a meditative atmosphere, facilitating deep concentration and emotional connection for both performers and listeners. The tanpura is typically played by a supporting musician or, in some cases, by the vocalist or instrumentalist themselves. In ensemble settings, multiple tanpuras may be used to enhance the richness and complexity of the drone. The instrument’s subtle variations in tone and resonance are carefully matched to the specific requirements of each raga, with advanced practitioners able to fine-tune the tanpura to reflect the unique flavor and mood of the performance.

Modern Developments and Electronic Tanpura

With the advent of technology, electronic tanpuras have been developed to replicate the sound of the traditional instrument. These compact devices and software applications provide a convenient alternative for practice and performance, especially when a live tanpura player is not available. However, many musicians and connoisseurs of Indian classical music consider the electronic tanpura to be a poor substitute for the nuanced, organic sound of the handcrafted instrument. The tactile interaction between the player and the tanpura, along with the subtle variations in tone produced by the natural materials and manual tuning, are seen as essential to the authenticity and emotional impact of the music.

Craftsmanship and Regional Variations

The art of tanpura making is a specialized craft passed down through generations of artisans, particularly in the town of Miraj. Skilled craftsmen select and cure the materials, shape the resonator and neck, and meticulously assemble the instrument to achieve the desired acoustic properties. Each tanpura is a unique creation, reflecting the expertise and artistic vision of its maker. Regional variations in design and construction are influenced by local materials, musical traditions, and aesthetic preferences. In North India, tanpuras are often made from large gourds, while in South India, jackwood is commonly used. Decorative elements such as inlays, carvings, and paintings may vary according to regional styles and the intended use of the instrument.

Playing Techniques and Sound Modifications

The tanpura is played in a manner that emphasizes the creation of a continuous, resonant drone, which forms the sonic bedrock of Indian classical music. The instrument is typically held upright in the lap or rested on the ground, though some musicians prefer to lay it across their lap for easier access to the tuning pegs and bridge. The position of the hand and fingers is crucial; the thumb supports the hand at the neck of the tanpura, while the fingers are placed parallel to and just above the center of the strings. This positioning allows for optimal resonance and ease of plucking. The act of plucking the strings is more of a gentle rolling or striking motion using the soft part of the fingertip rather than a sharp pluck. The first string is usually plucked with the middle finger, while the remaining strings are plucked with the index finger, one after another. The rhythm of plucking is steady but not mechanical, allowing the sound to breathe organically. Each string is given time to resonate, particularly the fourth string, which is allowed more time to fade away. The goal is to create a seamless, unbroken drone rich in overtones, which supports the main performer without drawing attention to itself.

Sound modifications on the tanpura are achieved through subtle adjustments. The bridge, known as the “jawari,” can be filed or shaped to alter the timbre and sustain of the strings, producing a characteristic buzzing resonance. Fine-tuning beads at the base of the strings allow for micro-adjustments in pitch, which is essential for matching the specific requirements of different ragas. The tuning itself is flexible and can be adapted to the raga, with common tunings including Sa, Pa, Sa, Sa or Sa, Ma, Sa, Sa, among others. These modifications enable the tanpura to provide a precise tonal reference and a rich harmonic environment.

Famous Compositions Featuring Tanpura

While the tanpura is not a melodic instrument and does not feature in compositions as a solo voice, it is indispensable in countless iconic performances and recordings of Indian classical music. Its presence is felt in every major raga performance, whether vocal or instrumental. Legendary recordings of ragas by maestros such as Pandit Bhimsen Joshi, Ustad Amir Khan, and M.S. Subbulakshmi are underscored by the hypnotic drone of the tanpura, which provides the essential tonal framework for their improvisations and compositions. In Dhrupad, the oldest surviving form of North Indian classical music, the tanpura’s drone is especially prominent and integral. The Dagar brothers, renowned Dhrupad exponents, have often emphasized the importance of the tanpura in their performances, using its drone to explore the depths of microtonal inflections and subtle ornamentations. Similarly, in Carnatic music, the tanpura is ever-present in the background of kritis by composers like Tyagaraja, Dikshitar, and Syama Sastri, ensuring the purity of pitch and enhancing the emotional impact of the compositions.

Most Influential Players

The tanpura is traditionally played by accompanying musicians, disciples, or even the main artist themselves, especially during practice sessions. While the instrument does not have solo virtuosos in the conventional sense, its mastery is highly respected among musicians. Many legendary vocalists and instrumentalists are known for their meticulous attention to the tuning and playing of the tanpura, considering it as much a part of their artistry as their primary instrument. Among the most influential figures associated with the tanpura are the Dagar family in Dhrupad, who have elevated the art of tanpura tuning and playing to a high level. Their performances are noted for the subtlety and richness of the drone, which is a result of their deep understanding of the instrument. Similarly, maestros like Ravi Shankar, Vilayat Khan, and Bismillah Khan have all emphasized the importance of the tanpura in their concerts, often personally overseeing its tuning and playing. In the modern era, the role of the tanpura player is sometimes filled by electronic tanpuras, but many artists still prefer the nuanced sound of a live instrument. Some contemporary musicians and teachers are recognized for their expertise in tanpura maintenance, tuning, and playing, ensuring that the tradition continues to thrive.

Historical Performances and Concerts

Throughout the history of Indian classical music, the tanpura has been present at every significant performance, from royal courts to modern concert halls. Its role is so fundamental that it is often taken for granted, yet no major recital is considered complete without its drone. Historical recordings of All India Radio broadcasts, legendary music conferences, and milestone concerts all feature the tanpura as the constant companion to the main artist. One notable example is the annual Sawai Gandharva Bhimsen Mahotsav in Pune, where the tanpura’s drone is a familiar backdrop to performances by the greatest names in Hindustani music. In Carnatic music, the Chennai Music Season is another event where the tanpura’s presence is ubiquitous, accompanying vocalists and instrumentalists alike in marathon concerts that can last for hours.

The tanpura’s role in these performances is not merely functional; it is deeply symbolic, representing the continuity of tradition and the unbroken thread of musical heritage. In recordings of historic concerts by artists like M.S. Subbulakshmi at the United Nations or Ravi Shankar at Woodstock, the tanpura’s drone serves as a bridge between cultures, grounding the music in its Indian roots while resonating with audiences worldwide.

Maintenance and Care

Proper maintenance and care of the tanpura are essential to preserve its delicate sound and structural integrity. The instrument should be protected from extreme temperatures and humidity, as these can cause the wood to warp and the gourd to crack. Regular cleaning with a soft, dry cloth helps prevent dust accumulation, which can dampen the instrument’s resonance. The strings, typically made of steel or brass, should be replaced periodically to maintain a clear, vibrant sound. Over time, strings can corrode or lose their elasticity, affecting the quality of the drone. The bridge, or jawari, requires special attention; it must be periodically checked and, if necessary, filed by a skilled artisan to ensure the characteristic buzzing resonance is maintained. Tuning pegs should be kept lubricated to allow smooth adjustment, and the fine-tuning beads at the base of the strings should be checked for wear. When not in use, the tanpura should be stored in a padded case to protect it from accidental damage. For those using electronic tanpuras, maintenance is minimal, but the unique acoustic qualities of a well-cared-for traditional tanpura remain unmatched.

Interesting Facts and Cultural Significance

The tanpura is often regarded as the “soul” of Indian classical music, providing the essential drone that underpins every performance. Its sound is said to represent the eternal “Om,” the primordial vibration from which all creation emerges. This spiritual dimension gives the tanpura a revered status among musicians and listeners alike. One fascinating aspect of the tanpura is its construction. The instrument is typically made from a single piece of wood for the neck and a resonating gourd for the body, though some modern versions use synthetic materials. The bridge is carefully shaped to produce the desired harmonic overtones, and the strings are chosen for their ability to sustain a long, resonant sound. The tanpura is also notable for its role in music education. Students of Indian classical music often begin their training by learning to play and tune the tanpura, developing an ear for pitch and harmony before moving on to more complex instruments or vocal techniques. This foundational training instills discipline and a deep appreciation for the subtleties of sound.

Culturally, the tanpura is a symbol of humility and service. The person playing the tanpura is often a disciple or accompanist, supporting the main artist without seeking the spotlight. This self-effacing role is highly valued in the Indian musical tradition, reflecting the ethos of collective creation and mutual respect. In recent years, the advent of electronic tanpuras has made the instrument more accessible, allowing students and performers to practice without the need for a live accompanist. However, many artists still prefer the warmth and complexity of a traditional tanpura, and some even combine both types for a richer sound.

The tanpura’s influence extends beyond classical music. It is used in devotional music, folk traditions, and even in contemporary fusion genres, demonstrating its versatility and enduring appeal. Its sound has been described as meditative and healing, and it is often used in music therapy and wellness practices.

FAQ

What materials are used in the construction of the Tanpura?

The Tanpura is traditionally crafted from a hollowed gourd (tumba) for the resonator, and seasoned wood for the neck and body. The bridge is often made from bone or ivory, and the strings are metal. The combination enhances its rich, continuous drone.

What are the different types of Tanpura?

There are mainly three types of Tanpura: male, female, and instrumental. Male Tanpuras are larger with a deeper tone, while female ones are smaller and more resonant. Instrumental Tanpuras are compact, designed to accompany instruments.

What is the primary use of the Tanpura in Indian classical music?

The Tanpura is used to provide a harmonic drone in Indian classical music. It supports vocalists and instrumentalists by maintaining the pitch and enhancing the tonal atmosphere during performances and practice sessions.

Links

Links

References

Other Instrument

Categories