Tembor

Plucked Instruments

Asia

Between 0 and 1000 AD

Video

The Tembor is a traditional long-necked lute integral to the musical heritage of the Uyghur people in Xinjiang, western China. Known for its intricate craftsmanship and resonant sound, it holds a revered status as “the father of music” within Uyghur culture. The instrument features a slender, elongated body and a neck adorned with fine geometric marquetry, reflecting the region’s artistic traditions. Its five steel strings are arranged in three courses, producing a bright, metallic timbre that complements vocal performances and classical Uyghur ensembles. The Tembor is distinguished by its use of a metal wire pick attached to the player’s index finger, allowing for precise plucking techniques. Its design incorporates both aesthetic and functional elements, such as a fish-shaped handguard to protect the musician’s fingers during vigorous play.

Type of Instrument: The Tembor belongs to the lute family of stringed instruments, classified as a composite chordophone under the Hornbostel-Sachs system. It shares structural and cultural ties with other Central Asian lutes like the dutar, setar, and tanbur, though it occupies a unique niche in Uyghur music. Unlike the dutar’s two-stringed simplicity or the tanbur’s Sufi ritual associations, the Tembor specializes in complex melodic lines and rhythmic accompaniment. It functions primarily as a solo and ensemble instrument in classical and folk repertoires, often accompanying poetic recitations and dance. Its role in Uyghur music emphasizes both technical virtuosity and emotional expression, bridging secular and ceremonial contexts.

History and Origins

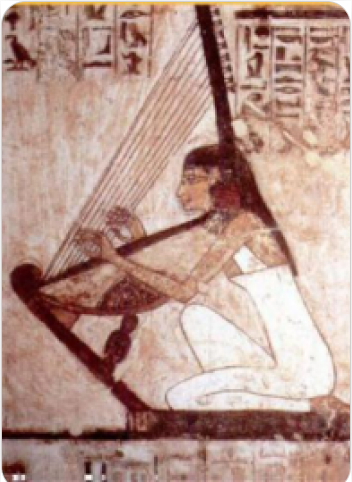

The Tembor, also spelled tambur or tanbur, is a long-necked plucked lute with deep historical roots in Central Asia. Its origin dates back to at least the 7th century, with early forms believed to have emerged on the continent of Asia, particularly within regions that are now parts of modern-day Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Xinjiang (China). The instrument is deeply tied to the musical traditions of Turkic, Uyghur, and Persian cultures, where it has been used to accompany epic poetry, classical music, and spiritual practices. Historical records and artworks from the medieval period of the Silk Road era suggest that the Tembor played a vital role in the musical exchange between Eastern and Western Asia. Over time, it evolved both in construction and technique, influenced by cultural interactions across Central Asia, the Middle East, and even parts of South Asia. Today, the Tembor remains an iconic symbol of Uyghur identity and heritage, particularly in the Xinjiang region of western China, where it is often featured in traditional maqam performances.

Construction and Physical Structure

The Tembor’s construction exemplifies traditional Uyghur luthiery, combining durability with ornamental elegance. Its body measures approximately 1.5 meters from headstock to base, carved from mulberry or apricot wood for optimal resonance. The neck, often inlaid with bone or mother-of-pearl patterns, hosts a semi-hollow channel to enhance projection. Five steel strings are anchored to a horn plate at the base and tuned to A A, D, and G G, creating a rich harmonic foundation. The soundboard features a guard plate shaped like a stylized fish, symbolizing prosperity in Uyghur folklore. Frets are absent, allowing for microtonal flexibility characteristic of Central Asian scales. The instrument’s marquetry includes geometric motifs inspired by Islamic art, applied using a painstaking mosaic technique.

Types and Variations

While the standard Tembor dominates Uyghur practice, regional variations exist in string configuration and decorative elements. Some versions incorporate additional sympathetic strings to deepen resonance, while others experiment with body shapes—such as slightly wider resonators for bass-heavy repertoires. The Ili Valley Tembor, considered the most authoritative model, prioritizes clarity in the upper registers for melodic prominence. In southern Xinjiang, Tembors may feature shorter necks for portability during outdoor festivities. These adaptations reflect local performance needs without compromising the instrument’s core identity.

Characteristics and Playing Technique

The Tembor’s playing technique demands exceptional dexterity, combining rapid plucking with subtle string bending. Musicians attach a metal pick to the right index finger, striking the strings with a combination of downstrokes and upstrokes to articulate complex rhythms. The left hand navigates the fretless neck, employing slides and vibrato to emulate vocal ornamentation. Its tuning enables both rhythmic ostinatos and soaring improvisations, often underpinning the Uyghur twelve-maqam system. The instrument’s metallic timbre cuts through ensemble textures, making it ideal for leading melodic lines. Advanced players exploit overtones by lightly touching harmonic nodes, producing ethereal effects in contemplative passages.

Cultural Significance and Modern Adaptations

In Uyghur society, the Tembor transcends mere musical function, embodying historical memory and communal identity. It features prominently in life-cycle ceremonies, from weddings to memorials, and serves as a pedagogical tool for transmitting oral histories. Contemporary musicians integrate the Tembor into fusion projects, pairing it with electronic effects or global instruments while preserving its acoustic essence. However, its sacred status ensures that traditional repertoires remain central, particularly the Ili school’s classical suites. As Xinjiang’s cultural landscape evolves, the Tembor persists as a testament to Uyghur creativity, bridging ancient soundscapes and modern innovation.

Comparative Analysis with Related Instruments

The Tembor’s closest relatives include the Persian tanbur and the dutar, though key differences define its unique profile. Unlike the tanbur’s gut strings and Sufi ritual use, the Tembor employs steel strings for brighter projection in secular settings. The dutar’s two-stringed design limits harmonic complexity, whereas the Tembor’s five strings enable chordal accompaniment and polyphonic textures. In contrast to the Kazakh dombra’s percussive attack, the Tembor emphasizes legato phrasing and dynamic subtlety. These distinctions highlight its specialized role in Uyghur music, balancing melodic leadership with textural support.

Challenges and Preservation Efforts

Modernization and cultural assimilation pressures threaten the Tembor’s traditional ecosystem. Master artisans face dwindling demand for handcrafted instruments, as factory-made models gain popularity. Educational initiatives, such as conservatory programs in Ürümqi and grassroots workshops, aim to sustain luthier skills and repertoire knowledge. Digital archives now document rare playing styles, ensuring their accessibility to future generations. International collaborations, including UNESCO recognition of Uyghur maqam, further bolster preservation, framing the Tembor as both a regional treasure and a global heritage artifact.

Playing Techniques and Sound Modifications

The tembor, a long-necked lute, is renowned for its expressive playing techniques and adaptability to various musical traditions. Players typically use a combination of finger picking and strumming, which allows for a broad palette of tones, ranging from soft, introspective phrases to bold and dynamic passages. The instrument’s fretless neck is a defining feature, enabling musicians to perform subtle pitch bends and microtonal inflections that are central to Middle Eastern and Central Asian music. These microtonal nuances allow the tembor to convey deep emotion and intricate melodic lines, often impossible on fretted instruments. In the Uyghur tradition, the tembor is played using a metal wire pick, which is attached under the fingernail of the right index finger with thread. This unique approach produces a crisp, articulate attack and allows for rapid, intricate plucking patterns. The left hand glides along the fretless neck, shaping the pitch and timbre with precise finger placement and subtle pressure variations. The instrument’s strings, arranged in courses and typically tuned to A A, D, G G, can be manipulated for both melodic and drone effects, providing a rich harmonic foundation.

Sound modifications are achieved through variations in picking technique, string damping, and the use of ornamentation such as slides, trills, and vibrato. The tembor’s construction, with its resonant mulberry wood body and thin soundboard, amplifies these nuances, resulting in a sound that is both warm and penetrating. In ensemble settings, players may also employ percussive effects by striking the body of the instrument or muting the strings to create rhythmic accents, further expanding the tembor’s expressive range.

Famous Compositions

The tembor is integral to the performance of traditional repertoires, particularly in the regions of Iran, Turkey, Central Asia, and Xinjiang. In Uyghur music, the tembor is a key instrument in the performance of the Muqam, a vast suite of musical modes, songs, and instrumental pieces that form the backbone of Uyghur classical music. These compositions, often performed in the Ili Valley, feature the tembor alongside the dutar and other traditional instruments, accompanying both solo and ensemble vocal performances. In the Middle Eastern context, the tembur is central to Sufi and Alevi spiritual music, where it is used to accompany devotional songs and rituals. Many of these compositions are centuries old, passed down through oral tradition and adapted by successive generations of musicians. The tembur’s haunting melodies and intricate ornamentation are essential to the emotional impact of these works, which often explore themes of love, longing, and spiritual transcendence.

Contemporary composers and performers have also contributed notable works to the tembor’s repertoire, blending traditional forms with modern influences. These compositions often showcase the instrument’s versatility, incorporating elements of jazz, classical, and world music to create new and innovative sounds.

Most Influential Players

Throughout its history, the tembor has been championed by a number of influential musicians who have shaped its development and expanded its reach. Among the most renowned are Şivan Perwer, a Kurdish musician celebrated for his virtuosic playing and powerful interpretations of traditional and contemporary Kurdish music. Seyed Khalil Alinejad was another master, known for his deep spiritual connection to the instrument and his contributions to Iranian and Kurdish musical traditions. Necdet Yaşar, a Turkish virtuoso, played a pivotal role in preserving and promoting the tembur within Turkish classical music. Murat Aydemir and Özer Özel are also highly regarded for their technical mastery and innovative approaches, blending traditional techniques with modern sensibilities. In the Uyghur tradition, the tembor is revered as “the father of music,” and its leading exponents are held in high esteem. Performers such as Yalda Abassi, Cemil Qoçgiri, and Ali Doğan Gönültaş have brought the instrument to international audiences, demonstrating its expressive power and cultural significance. Their performances, both in solo and ensemble settings, highlight the tembor’s unique voice and its central role in the musical life of their communities.

Historical Performances or Concerts

The tembor has featured prominently in a wide array of historical performances and concerts, both within its regions of origin and on the global stage. In Central Asia and the Middle East, the instrument has long been a fixture at festivals, religious ceremonies, and cultural gatherings. Its evocative sound accompanies rituals, dances, and storytelling, providing a musical link between past and present. In recent decades, the tembor has gained international recognition through performances at world music festivals and cross-cultural collaborations. Notable events include appearances at the Polirítmia festival, where artists such as Ali Doğan Gönültaş have captivated audiences with their skillful playing and deep musicality. These concerts often feature traditional repertoires as well as contemporary compositions, showcasing the tembor’s adaptability and enduring appeal.

The instrument’s role in spiritual and ceremonial contexts is particularly significant. In Sufi and Alevi gatherings, the tembor’s melodies serve as a conduit for meditation and communal reflection, enhancing the spiritual atmosphere and fostering a sense of unity among participants. Historical performances in these settings are often marked by improvisation and emotional intensity, reflecting the deep connection between the musician, the instrument, and the audience.

Maintenance and Care

Proper maintenance and care are essential to preserving the tembor’s distinctive sound and ensuring its longevity. The instrument’s body, typically crafted from a single piece of mulberry wood, requires regular cleaning to prevent the buildup of dust and oils, which can affect its resonance and appearance. The soundboard, often adorned with intricate marquetry, should be handled with care to avoid scratches and damage to the decorative elements. The strings, whether made of silk, nylon, or steel, must be inspected regularly for signs of wear and replaced as needed to maintain optimal tone and playability. Tuning the tembor is a delicate process, as the tension and balance of the strings directly influence the instrument’s intonation and response. Players should use appropriate tuning methods and avoid over-tightening, which can stress the neck and body.

The metal wire pick, a distinctive feature in Uyghur tembor playing, should be kept clean and securely attached to ensure consistent articulation. The fish-shaped hand guard and other decorative elements require gentle cleaning to preserve their beauty and functionality. When not in use, the tembor should be stored in a protective case, away from extreme temperatures and humidity, which can cause the wood to warp or crack. Periodic professional maintenance, including adjustments to the neck, bridge, and soundboard, is recommended to address any structural issues and ensure the instrument remains in top condition. With proper care, the tembor can provide decades of musical enjoyment and artistic expression.

Interesting Facts and Cultural Significance

The tembor holds a unique place in the musical and cultural heritage of the regions where it is played. Known as “the father of music” in Uyghur tradition, the instrument is revered for its complexity and expressive potential. Its role in the Muqam suites of Xinjiang underscores its importance as both a solo and ensemble instrument, capable of conveying a wide range of emotions and musical ideas. Culturally, the tembor is closely associated with spiritual and ceremonial practices, particularly in Sufi and Alevi communities. Its melodies are believed to facilitate meditation, reflection, and communal bonding, making it an essential component of religious and social gatherings. The instrument’s presence in these contexts highlights its power to transcend the boundaries of language and culture, uniting people through shared musical experiences.

The tembor’s construction is a testament to the artistry and craftsmanship of its makers. The use of mulberry wood, intricate marquetry, and unique design features such as the fish-shaped hand guard reflect the cultural values and aesthetic sensibilities of the communities that produce and play the instrument. Each tembor is a work of art, imbued with the history and identity of its makers. In recent years, the tembor has attracted the attention of musicians and audiences worldwide, thanks to the efforts of influential performers and the growing interest in world music. Its haunting sound and rich tradition have inspired collaborations across genres, bringing the instrument to new audiences and ensuring its continued relevance in the global musical landscape.

The tembor’s adaptability is further demonstrated by the variety of playing styles and tunings found across different regions. From the intricate microtonal melodies of the Middle East to the rhythmic patterns of Uyghur music, the instrument serves as a bridge between diverse musical traditions, fostering cross-cultural understanding and appreciation.

FAQ

What type of instrument is the Tembor?

The Tembor is a long-necked lute traditionally used in Uyghur music. It falls under the category of string instruments, specifically plucked lutes. Its resonant sound is central to many traditional folk performances. It typically features sympathetic strings to enhance its tonal depth.

What is the historical origin of the Tembor?

The Tembor originates from the Xinjiang region of China, historically associated with the Uyghur ethnic group. Its roots trace back to the Silk Road era, where it evolved from earlier Central Asian lutes. It reflects centuries of cultural exchange across Eurasia. It remains a symbol of Uyghur heritage today.

What materials are used in constructing the Tembor?

Tembors are typically made from mulberry or apricot wood for the body, with strings made from steel or silk. The fingerboard may be inlaid with decorative elements like bone or shell. The craftsmanship involves intricate carving and traditional ornamentation. Each Tembor is often handmade by skilled artisans.

Links

Links

References

Other Instrument

Categories