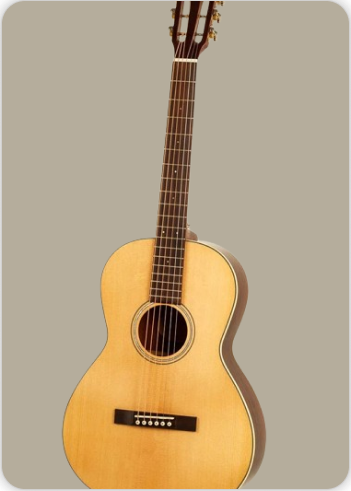

Tritantri Vina

Plucked Instruments

Asia

Ancient

Video

The Tritantri Vina, also known as Tri-tantri Veena or Jantra, is a historic three-stringed lute originating from the Indian subcontinent. Classified as a chordophone, it belongs to the broader family of veenas—a term historically encompassing various stringed instruments in Indian tradition. Unlike later veenas with multiple strings and frets, the Tritantri Vina was a simple, fretless instrument played by plucking its three strings directly. Its design focused on melodic flexibility, allowing performers to explore microtonal nuances characteristic of Indian classical music. The instrument’s name directly references its three strings (*tri* meaning “three” and *tantri* meaning “strings”), distinguishing it from other veenas like the Saraswati Veena or Rudra Veena, which evolved with more complex structures.

Type of Instrument

The Tritantri Vina is categorized as a lute-type chordophone. It shares similarities with ancient Indian instruments like the ektara (one-string lute) but features a more developed structure with three melody strings. Unlike zither-style veenas such as the Saraswati Veena or stick-zither variants like the Rudra Veena, the Tritantri Vina’s fretless neck and compact design made it portable and adaptable for folk and devotional music. Its playing technique involved direct string plucking without the use of a plectrum, emphasizing fluid glides between notes, a precursor to the portamento techniques later seen in instruments like the sitar.

History of Tritantri Vina

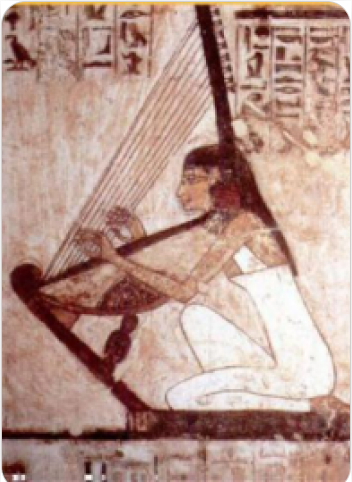

The Tritantri Vina’s origins trace back to medieval India, likely between the 12th and 15th centuries, during a period of cultural exchange between Indian and Persian musical traditions. Early references to similar instruments appear in Sanskrit texts, where the term *veena* broadly described stringed instruments. The Tritantri Vina’s three-stringed design emerged as an evolution from simpler one-string lutes like the Ek Tantri Veena, reflecting advancements in musical expression. Its prominence grew in folk and courtly settings, serving as a tool for minstrels and devotional singers. The instrument’s design caught the attention of Muslim invaders, who adapted it into the Persian-influenced *seh-tar* (“three strings”), later evolving into the modern sitar. This cross-cultural exchange positioned the Tritantri Vina as a critical link between ancient Indian lutes and the Hindustani classical instruments that dominate North Indian music today.

Construction and Physical Structure

The Tritantri Vina’s construction centered on simplicity and functionality. Its body typically consisted of a hollow wooden resonator, often carved from a single piece of jackfruit or teak wood, attached to a cylindrical neck. The three gut or silk strings ran from tuning pegs at the top of the neck to a tailpiece anchored on the resonator. Unlike later veenas, it lacked frets, allowing performers to manipulate pitch freely by pressing strings along the smooth neck. The resonator, sometimes reinforced with animal hide or gourd attachments, amplified the sound, though its volume remained modest compared to instruments with sympathetic strings. The absence of decorative elements like the gourd resonators seen in Rudra Veena or the ornate carvings of Saraswati Veena underscored its utilitarian role in folk traditions.

Types of Tritantri Vina

While the Tritantri Vina itself represents a specific three-stringed design, its name occasionally appears interchangeably with regional variants of fretless lutes. The *Jantra*, mentioned in medieval texts, shared its three-stringed configuration but sometimes incorporated a slightly longer neck. Another related instrument, the *Do Tantri Veena* (two-string lute), represented an earlier evolutionary stage. However, the Tritantri Vina’s primary distinction lay in its three strings, which enabled richer melodic possibilities than its predecessors. Later derivatives, such as the sitar, expanded the string count and introduced frets, but the Tritantri Vina remained a foundational model for these developments.

Characteristics

The Tritantri Vina’s defining characteristics included its fretless neck, three melody strings, and focus on microtonal expression. Performers utilized slides and bends to achieve the *meend* (gliding between notes) central to Indian ragas. Its tuning varied regionally but often emphasized a tonic, fifth, and octave relationship between strings, creating a harmonic foundation for improvisation. The absence of drone or sympathetic strings—common in later veenas—required players to maintain rhythmic and melodic continuity through fingerstyle techniques. Its intimate, resonant timbre suited both solo performances and accompaniment for vocalists, particularly in devotional and folk genres. The instrument’s adaptability to oral teaching traditions made it a staple in rural musical practices, preserving ancient melodic forms that influenced classical raga structures.

Evolution and Legacy

The Tritantri Vina’s decline coincided with the rise of more sophisticated instruments like the sitar and sarod in the Mughal era. However, its legacy persists in the structural and technical foundations of Hindustani classical music. The sitar’s three primary playing strings, for instance, directly echo the Tritantri Vina’s design, while its fretless playing style influenced techniques used in the vichitra veena and sarangi. Modern reconstructions of the instrument, though rare, offer insights into pre-Mughal Indian music, highlighting its role as a cultural bridge between folk and classical traditions. Ethnomusicologists regard the Tritantri Vina as a testament to India’s innovative spirit in stringed instrument design, showcasing how minimalist structures can yield profound musical complexity.

Comparisons with Later Veenas: Unlike the Saraswati Veena’s fixed frets and four melodic strings, the Tritantri Vina’s fretless design allowed unrestricted pitch exploration. The Rudra Veena’s addition of drone strings and gourds for resonance marked a departure from the Tritantri Vina’s compact form, reflecting evolving preferences for sustained tones in dhrupad music. The Vichitra Veena, though fretless, adopted a slide-based technique and added sympathetic strings, showcasing how later instruments expanded on the Tritantri Vina’s core principles. These comparisons highlight the Tritantri Vina’s role as a transitional instrument, bridging the gap between ancient lute traditions and the specialized veenas of the classical era.

Acoustic Properties: The Tritantri Vina’s sound production relied on the direct vibration of its three strings, transmitted through the wooden resonator. The absence of metal components (common in later instruments) resulted in a warmer, softer timbre, ideal for intimate settings. Its limited volume made it unsuitable for large ensembles, but this constraint encouraged nuanced playing styles that prioritized tonal subtlety over projection. The gut strings, responsive to finger pressure, enabled dynamic expression, while the hollow neck contributed to a distinctive sustain, blending plucked notes into seamless phrases.

Revival and Modern Adaptations: Recent efforts by instrument makers and scholars have sought to reconstruct the Tritantri Vina using descriptions from medieval texts and iconographic evidence. These replicas, though speculative, demonstrate the instrument’s compatibility with contemporary raga frameworks. Some fusion musicians experiment with hybrid designs, integrating electronic pickups or additional strings while retaining the original’s fretless neck. These adaptations aim to reintroduce the Tritantri Vina’s organic sound into modern genres, bridging historical and avant-garde musical expressions. However, its niche status underscores the challenges of reviving obsolete instruments in a rapidly globalizing music industry.

Playing Techniques and Sound Modifications

The Tritantri vina, a precursor to the modern sitar, is a stringed instrument traditionally featuring three strings. Its playing techniques blend plucking and finger movements to produce intricate melodic patterns and gamakas (ornamentations). The right hand typically employs a plectrum or mizrab worn on the index finger to pluck the strings in both upward and downward motions, producing rhythmic syllables known as bols such as “DA” (upward pluck) and “RA” (downward pluck). Successive plucking in quick succession, called “DIR,” adds rhythmic complexity. The left hand manipulates the strings on the frets to create slides (portamento) and bends, essential for the gayaki ang or vocal style of playing. This includes pulling strings upward to reach higher notes and gliding smoothly between frets to connect notes seamlessly. The frets are often curved elliptically, allowing nuanced string deflections to achieve microtonal variations characteristic of Indian classical music. The combination of these techniques enables the Tritantri vina to produce a rich, expressive sound that can mimic the human voice, with both rhythm and melody interwoven in performance.

Sound modifications also involve tuning adjustments using wooden or metal tuning pegs to control string tension and pitch. The bridge, often shaped carefully in a process called jawari, influences the tonal quality and sustain of the instrument. Players may also use artificial nails or plectra to enhance volume and clarity. The instrument’s sympathetic strings, if present, resonate to enrich the soundscape, though the Tritantri vina traditionally has fewer sympathetic strings compared to its descendants. These techniques and modifications collectively define the unique sonic character of the Tritantri vina, making it a versatile instrument in classical Indian music traditions.

Famous Compositions

While specific compositions exclusively attributed to the Tritantri vina are less documented due to its historical nature, many classical ragas and compositions performed on the sitar and other veena variants have roots tracing back to this instrument. The Tritantri vina was primarily used for elaborating ragas that emphasize melodic development and gamaka. Traditional compositions in ragas such as Yaman, Bhairav, and Kafi, which are staples of Hindustani classical music, would have been adapted for the Tritantri vina. These compositions typically involve alap (slow, improvised introduction), jor (rhythmic development), and gat (fixed composition set to a tala or rhythmic cycle). The instrument’s ability to render subtle pitch bends and slides made it suitable for compositions that require expressive melodic phrasing.

Most Influential Players

Due to the Tritantri vina’s historical status as an ancestor of the sitar, many of the early influential players are not individually documented. However, the evolution from the Tritantri vina to the sitar involved prominent musicians and instrument makers who refined playing techniques and instrument design. The lineage of sitar maestros such as Ustad Vilayat Khan and Pandit Ravi Shankar can be seen as inheritors of the Tritantri vina’s musical tradition, as they developed and popularized the playing styles that originated from this instrument. These artists expanded the expressive capabilities of the instrument, incorporating complex right- and left-hand techniques and introducing new tonal nuances. Their performances and teachings helped establish the sitar—and by extension, the Tritantri vina’s legacy—as a central instrument in Hindustani classical music.

Historical Performances or Concerts

Historical records of specific concerts featuring the Tritantri vina are scarce, as the instrument predates modern concert traditions and recording technologies. It was primarily played in royal courts and temple settings during medieval and early modern periods in India, where it accompanied vocal performances or was used for solo instrumental renditions of ragas. These performances were intimate and often part of religious or ceremonial occasions. Over time, as the Tritantri vina evolved into the sitar, it gained prominence on concert stages across India and internationally. The transition marked a shift from private court performances to public concerts, where the instrument’s capabilities could be showcased to larger audiences. The sitar’s rise in the 20th century brought the musical heritage of the Tritantri vina to global attention.

Maintenance and Care

Maintaining a Tritantri vina involves regular tuning, cleaning, and careful handling to preserve its delicate wooden body and strings. The tuning pegs, traditionally made of wood, require periodic adjustment to maintain string tension and pitch stability. Because wooden pegs are sensitive to humidity and temperature changes, some modern players replace them with metal guitar-style tuning pegs for better durability and fine tuning. The strings, made of metal or gut, need to be replaced periodically to ensure optimal sound quality. The bridge must be kept clean and sometimes reshaped to maintain the desired jawari effect, which influences the instrument’s tonal character.

The wooden body and resonators should be wiped gently with a soft cloth to remove dust and oils from the hands. Players often store the instrument in a protective case to prevent damage from environmental factors. Proper care extends the life of the instrument and preserves its sound quality, allowing it to maintain the rich tonal nuances essential for classical performance.

Interesting Facts and Cultural Significance

The Tritantri vina holds a significant place in the history of Indian classical music as a direct precursor to the sitar, one of the most iconic instruments of Hindustani music. Its name, “Tritantri,” literally means “three-stringed,” highlighting its distinctive string configuration compared to other veenas. This instrument represents a crucial evolutionary link in the development of Indian string instruments, bridging ancient veena designs and the modern sitar. Culturally, the Tritantri vina was associated with spiritual and scholarly traditions. It was often played in temples and royal courts, symbolizing divine music and scholarly refinement. The instrument’s ability to mimic the human voice made it a favored tool for expressing the emotive and devotional aspects of ragas. Its design and playing style influenced not only the sitar but also other string instruments like the sarod and sarangi, underscoring its broad impact on Indian music.

The Tritantri vina’s legacy continues through its descendants and the musical techniques it inspired. Its role in shaping the melodic and rhythmic frameworks of Indian classical music underscores its enduring cultural importance. Today, it is studied by musicologists and performers interested in the historical development of Indian string instruments and classical music traditions.

FAQ

What is the construction and material used in the Tritantri Vina?

The Tritantri Vina is made using a single piece of wood with a hollowed body and three strings stretched over a wooden bridge. Its resonator is carved directly from the same wood, giving it a compact and monolithic build.

What are the types and features of the Tritantri Vina?

Historically, the Tritantri Vina appeared in small, portable forms, usually as a practice instrument. It features three metal strings and a series of fixed frets that enable melodic and rhythmic exercises in classical Indian music.

What are the applications and uses of the Tritantri Vina in music?

The Tritantri Vina is mainly used for practice and instruction in Indian classical music, particularly for students of the veena or sitar. Its small size and simplicity make it ideal for mastering fingering techniques and raga structures.

Links

Links

References

Other Instrument

Categories