Tungna

Plucked Instruments

Asia

Between 1001 and 1900 AD

Video

The Tungna is a traditional plucked string instrument, deeply rooted in the musical heritage of the Himalayan regions, particularly Nepal, Tibet, Sikkim, and Bhutan. This instrument is renowned for its distinct, resonant sound and its unique construction, which involves carving the entire body from a single piece of wood. The front of the instrument, forming the sound box, is covered with stretched animal skin, typically goat or buffalo, over which the bridge is placed. The Tungna is fitted with four strings, which were historically made from animal gut but are now more commonly fashioned from nylon or fishing wire. These strings are anchored at both ends—one to the tuning keys and the other to the body—while the bridge acts as a cantilever, maintaining the necessary tension for sound production.

The Tungna holds a special place in the cultural life of Himalayan communities, especially among the Tamang, Sherpa, Gurung, and Tibetan people. It is often played during festivals, auspicious occasions, and communal gatherings, where musicians accompany their playing with singing, often composing songs to mark significant events such as the New Year or harvest celebrations. The instrument is not only a vehicle for musical expression but also a symbol of communal identity and tradition, with many households in the region possessing at least one Tungna.

Type of Instrument

The Tungna is classified as a plucked string instrument, specifically a type of lute. More precisely, it falls under the category of drumhead lutes due to its construction, which involves a membrane (animal skin) stretched over a hollow body to form the soundboard. This design is similar to other lutes found across Central and South Asia, such as the rubab and the dramyin. The Tungna is typically played by plucking the strings with the fingers or with a plectrum, producing a warm, mellow tone that is characteristic of the instrument.

History of the Tungna

The history of the Tungna is intertwined with the cultural evolution of the Himalayan region. Its origins can be traced to the mountainous areas of Nepal, Tibet, Sikkim, and Bhutan, making it a distinctly Himalayan instrument. The instrument is believed to have developed alongside the migration and settlement patterns of ethnic groups such as the Tamang, Sherpa, Hyolmo, and Tibetan peoples, who brought their musical traditions with them as they moved across the region. The Tungna shares historical and structural similarities with other ancient lutes found throughout Asia, such as the Iranian rubab from the 13th century and the Mongolian lute from the late 13th century. These connections suggest that the Tungna, or its precursors, may have been present in the Himalayan region as early as the first millennium CE, evolving over centuries in response to local musical needs and aesthetic preferences.

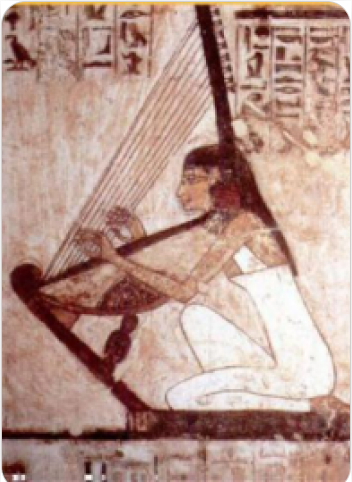

By the 8th century, instruments similar to the Tungna were already prominent in the cultural life of Bhutan and Tibet, as evidenced by their depiction in religious art and their association with Buddhist saints and deities. The Tungna’s continued presence in the region over the centuries attests to its enduring appeal and its role as a vessel for the transmission of oral history, folklore, and communal identity.

Construction and Physical Structure

The construction of the Tungna is a testament to the craftsmanship and ingenuity of Himalayan artisans. The instrument is typically carved from a single block of lightweight, resonant wood, such as Nepalese alder (uttis), rhododendron, or schima (chilaune). These woods are favored for their acoustic properties and their availability in the Himalayan region. The body of the Tungna is hollowed out to create a resonating chamber, with the front covered by a tightly stretched piece of animal skin, usually goat or buffalo. This membrane serves as the soundboard, amplifying the vibrations produced by the strings. The neck of the Tungna extends from the body and is often adorned with intricate carvings, including representations of animals—both real and mythical—such as dragons, horses, birds, or the garuda, a demigod figure in Hindu and Buddhist mythology. These carvings are not merely decorative; they are imbued with cultural and spiritual significance, reflecting the beliefs and traditions of the communities that play the instrument.

At the end of the neck is the headstock, which houses the tuning keys. Traditionally, these keys were made from wood or animal bone and are used to adjust the tension of the strings. The Tungna typically has four strings, which are anchored at the base of the body and run over the bridge, which is positioned on the animal skin soundboard. The bridge is designed to act as a cantilever, maintaining the proper tension for each string. While gut strings were once standard, modern Tungnas often use nylon or fishing wire, which, while more durable and accessible, impart a slightly different tonal quality. The instrument varies in size, with medium-sized Tungnas measuring around 30 to 36 inches in length and 7 to 8 inches in width. The weight is generally light, making the Tungna portable and easy to handle during performances. The entire construction process is typically done by hand, with each instrument reflecting the skill and artistic sensibility of its maker.

Types of Tungna

There are several regional and stylistic variations of the Tungna, each reflecting the musical traditions and preferences of different Himalayan communities. The main types can be broadly categorized as follows:

Tamang Tungna: This variant is associated with the Tamang community of Nepal. It is generally short-necked and features a dragon headstock. The Tamang Tungna is distinguished by its craftsmanship, size, playing style, and tuning system. It is often used to accompany folk songs and dances, with a focus on narrative storytelling.

Sherpa and Tibetan Tungna (Dramyin or Dhamyen): These versions are long-necked, with longer strings and fewer decorative elements compared to the Tamang Tungna. The Sherpa and Tibetan Tungna are closely related to the dramyin, a similar lute found in Bhutan and Tibet. These instruments are integral to communal dance and song, with the music often accompanying choreographed dance steps.

Bhutanese Drangyen: While not always classified as a Tungna, the drangyen shares many structural and musical similarities. It is the national instrument of Bhutan and features a distinctive chusin-shaped head, often carved to resemble a sea monster. The drangyen is typically larger, with seven strings and two bridges, and is played with a plectrum.

Modern Variants: Contemporary Tungnas may incorporate different materials and construction techniques, such as the use of nylon strings and machine-made components. These modern instruments are designed for durability and consistency, catering to the needs of professional musicians and enthusiasts alike.

Characteristics of the Tungna

The Tungna is characterized by its warm, mellow tone, which is produced by the combination of its wooden body, animal skin soundboard, and gut or nylon strings. The instrument’s sound is both resonant and intimate, making it well-suited for solo performances as well as accompaniment in group settings. The tonal quality of the Tungna can vary depending on the materials used, the skill of the maker, and the playing technique employed. One of the defining features of the Tungna is its role in the cultural and social life of Himalayan communities. The instrument is more than just a musical tool; it is a symbol of identity, tradition, and communal belonging. Songs played on the Tungna often recount local legends, historical events, and personal stories, serving as a means of preserving and transmitting oral history. The act of playing the Tungna is often accompanied by singing and dancing, creating a vibrant, participatory musical experience.

The Tungna is also notable for its craftsmanship and aesthetic appeal. Each instrument is a unique work of art, with intricate carvings and decorations that reflect the cultural heritage of its maker. The headstock, in particular, is often the focal point of artistic expression, with animal motifs that are believed to confer protection, good fortune, or spiritual power. In terms of playability, the Tungna is relatively accessible to beginners, with a straightforward tuning system and a manageable number of strings. However, mastering the instrument requires skill and practice, particularly in achieving the desired tonal quality and expressive range. The Tungna can be played solo or as part of an ensemble, and its versatility has allowed it to adapt to a wide range of musical genres, from traditional folk music to contemporary fusion.

Playing Techniques and Sound Modifications

The Tungna is traditionally played by plucking or strumming its strings, often using a wooden plectrum. The playing technique is deeply rooted in the folk traditions of Himalayan communities, and it is common for musicians to accompany their playing with singing and dancing. The instrument is typically held horizontally across the lap, with the left hand pressing the strings along the fretless neck to alter pitch, while the right hand strums or plucks the strings. This allows for a fluid, expressive style, with the absence of frets enabling subtle slides and microtonal variations. Players can modify the sound of the Tungna by adjusting the tension of the strings using the wooden or bone tuning pegs on the headstock. Historically, the strings were made from sheep or goat gut, producing a warm, organic tone. Modern Tungnas often use nylon or fishing wire, which changes the timbre, making it brighter and less mellow compared to the original gut strings. The bridge, which sits on the animal skin soundboard, also affects the instrument’s resonance and sustain. Some musicians experiment with different bridge shapes or materials to further customize the sound.

The skin covering the bowl-shaped body plays a crucial role in the Tungna’s unique timbre. The choice of animal skin (commonly buffalo or goat) and its tightness can be adjusted to influence the instrument’s resonance and volume. Additionally, the hollow wooden body, carved from a single piece of wood, acts as a resonator, amplifying the sound and contributing to the instrument’s characteristic warmth and projection.

Famous Compositions

While the Tungna is primarily associated with folk music and is rarely used in formal classical compositions, it features prominently in traditional songs and dances of the Tamang, Sherpa, Hyolmo, and Tibetan communities. Many compositions are passed down orally and are closely linked to rituals, festivals, and communal gatherings. Songs played on the Tungna often celebrate the New Year, harvests, or significant life events, with lyrics reflecting the joys and hardships of mountain life. Some well-known folk compositions include Tamang Selo songs, which are lively, rhythmic pieces integral to Tamang cultural celebrations. These songs are often accompanied by dance and are characterized by their driving rhythms and repetitive melodic patterns. The Tungna’s role is to provide both melodic and rhythmic support, often interweaving with vocals and other traditional instruments.

In recent years, contemporary Nepali folk artists and bands have incorporated the Tungna into new arrangements, blending it with modern instruments and genres. This has led to a resurgence of interest in the instrument and the creation of new compositions that pay homage to its roots while exploring new musical territories.

Most Influential Players

The Tungna’s legacy is preserved and advanced by master musicians, instrument makers, and folk artists from Himalayan communities. While many influential players remain local legends rather than international celebrities, their contributions are vital to the instrument’s survival and evolution. Agrim Lama, a renowned luthier from Lalitpur, is known for his expertise in crafting Tamang Tungnas and for his efforts to promote the instrument. His work ensures that traditional knowledge is passed on to future generations and that high-quality Tungnas remain available to musicians. Navneet Aditya Waiba, a prominent folk singer, has helped bring the Tungna to wider audiences by featuring it in her performances and recordings. Her work with traditional Nepali music has inspired a new generation of musicians to embrace the Tungna and other indigenous instruments.

In community settings, Tungna players are often respected elders or cultural custodians who lead performances during festivals and ceremonies. Their improvisational skills and deep understanding of local musical traditions make them influential figures within their communities.

Historical Performances or Concerts

The Tungna has a long history of being played at significant cultural events, including New Year celebrations, harvest festivals, weddings, and religious ceremonies. In the Himalayan regions of Nepal, Tibet, Sikkim, and Bhutan, historical performances often involved communal gatherings where the Tungna provided the musical foundation for singing, dancing, and storytelling. One of the most important contexts for Tungna performance is the Tamang Selo dance, a vibrant and energetic folk dance of the Tamang people. The Tungna’s rhythmic strumming and melodic lines drive the dance, creating a lively atmosphere that brings communities together. In recent decades, the Tungna has appeared on national and international stages through folk music festivals and cultural exchange programs. These performances have introduced the instrument to wider audiences and highlighted its role as a symbol of Himalayan cultural identity.

Maintenance and Care

Proper maintenance is essential to preserve the Tungna’s sound quality and longevity. The instrument should be stored in a dry, cool place to prevent damage to the wood and skin. Excessive humidity can cause the animal skin to loosen or deteriorate, while extreme dryness may lead to cracking. The strings, whether gut or nylon, should be checked regularly for signs of wear and replaced as needed. Nylon strings are more durable and easier to maintain than traditional gut strings, but they may require more frequent tuning due to changes in temperature and humidity. The wooden body and neck should be cleaned gently with a soft, dry cloth. If the instrument is painted or decorated, care should be taken to avoid scratching or damaging the surface. Periodic inspection of the tuning pegs and bridge is recommended to ensure they remain secure and functional. For instruments with intricate carvings or painted designs, it is advisable to consult an experienced luthier for any repairs or restoration work. Proper care not only maintains the instrument’s appearance and sound but also honors the craftsmanship and cultural heritage it represents.

Interesting Facts and Cultural Significance

The Tungna is more than just a musical instrument; it is a cultural icon in the Himalayan regions. Its construction from a single piece of wood, often adorned with carvings of animals or mythical creatures, reflects both artistic skill and spiritual beliefs. The headstock may feature representations of dragons, horses, birds, or the Garuda, a demigod revered in Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain traditions. According to legend, the eyes of the carved animal should gaze directly at the press board, symbolizing a harmonious relationship between the musician and the spirit of the instrument. The Tungna is closely associated with the Tamang, Sherpa, Hyolmo, and Tibetan communities, each of which has developed unique styles and variations. For example, the Tamang Tungna is typically short-necked with a dragon headstock, while Sherpa and Tibetan versions, sometimes called Dramyin or Dhamyen, are longer-necked and less ornate.

In many Himalayan households, the Tungna is a cherished possession, often passed down through generations. It is played during auspicious occasions and is believed to bring good fortune and unity to the community. The instrument’s music accompanies rituals, dances, and storytelling, serving as a bridge between the past and present. The Tungna’s role in promoting communal harmony and cultural identity cannot be overstated. Its music fosters a sense of belonging and continuity, especially in remote mountain villages where traditions are maintained through oral transmission. Even as modern influences and mass-produced instruments become more prevalent, the Tungna endures as a symbol of resilience and creativity.

Efforts to preserve and promote the Tungna are ongoing, with musicians, artisans, and cultural organizations working to ensure that the instrument remains a vibrant part of Himalayan heritage. Workshops, performances, and educational programs introduce new generations to the Tungna’s unique sound and significance, helping to keep its legacy alive.

Cultural Significance and Modern Revival

The Tungna’s cultural significance extends beyond its musical function. It is a vessel for storytelling, a companion in celebration and mourning, and a symbol of the interconnectedness of Himalayan peoples. The instrument’s presence at festivals and ceremonies underscores its role as a unifying force, bringing together individuals of all ages and backgrounds. In recent years, the Tungna has experienced a revival, thanks in part to the efforts of folk musicians and cultural advocates. Contemporary artists are experimenting with new materials, designs, and playing techniques, blending traditional sounds with modern genres. This fusion has introduced the Tungna to urban audiences and international listeners, ensuring its continued relevance in a rapidly changing world.

The Tungna’s journey from remote mountain villages to global stages is a testament to its enduring appeal and adaptability. As both a work of art and a tool for expression, the Tungna continues to inspire musicians and listeners alike, embodying the spirit and resilience of the Himalayan people.

FAQ

What is the construction of the Tungna and what materials are used?

The Tungna is carved from a single piece of wood, traditionally from softwood like rhododendron. It has a hollowed-out body with a skin soundboard made from animal hide. It typically features three to four strings made from animal gut or synthetic materials. The neck is fretless, allowing for smooth melodic slides.

What are the main types and features of the Tungna?

Types of Tungna vary by region in Nepal, with differences in size, string number, and tuning. Some have ornate carvings or symbolic designs. Key features include its light weight, portability, and warm, resonant tone. Its fretless neck enables expressive pitch bending and glides.

What is the historical and cultural significance of the Tungna?

The Tungna is deeply rooted in the Himalayan regions of Nepal and Tibet, especially among the Tamang and Sherpa communities. Historically, it has been used in storytelling, rituals, and folk songs. It holds spiritual significance and often accompanies Buddhist chants. Its sound reflects Himalayan heritage and mountain life.

Links

Links

References

Other Instrument

Categories