Vichitra veena

Plucked Instruments

Asia

Between 1001 and 1900 AD

Video

The Vichitra Veena is an extraordinary stringed instrument, celebrated for its unique design and ethereal sound within the realm of North Indian classical music. Unlike many other Indian string instruments, the Vichitra Veena is fretless, allowing for a continuous, fluid glissando and intricate melodic ornamentation. Its name, “Vichitra,” means “peculiar” or “wondrous,” reflecting both its striking appearance and the unusual technique required to play it. The instrument is typically placed horizontally in front of the player, who sits cross-legged on the floor. Its body comprises a long, wide, and flat wooden plank, known as the “dand,” which is supported at each end by large, resonating gourds called “tumba.” These gourds, often ornately decorated, serve as the primary sound chambers, amplifying the instrument’s deep, meditative tone.

Type of Instrument

The Vichitra Veena belongs to the category of chordophones, specifically classified as a plucked stick zither. In the Indian system of musical instrument classification, it is a “Tat Vadya,” which refers to stringed instruments that produce sound primarily by the vibration of stretched strings. More precisely, the Vichitra Veena is a fretless, horizontal zither, distinguished by its lack of fixed frets and its use of a sliding object to modulate pitch. This places it in the same general family as other Indian veenas, such as the Rudra Veena and the Chitra Veena (Gottuvadhyam), though it is unique in its construction and playing technique.

History of the Vichitra Veena

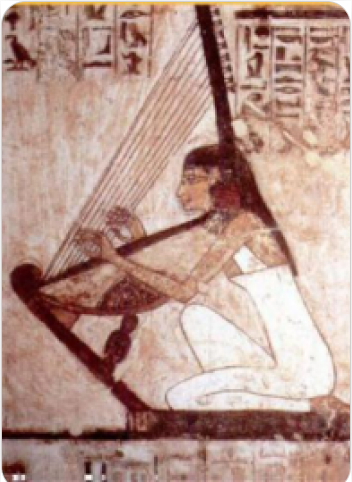

The history of the Vichitra Veena is deeply intertwined with the evolution of Indian classical music and the broader history of stringed instruments in South Asia. Its origins can be traced back to the ancient veenas described in Vedic literature, making it one of the oldest surviving types of Indian string instruments. The veena, in its various forms, has been a symbol of Indian musical and spiritual culture for millennia, often depicted in the hands of Saraswati, the goddess of knowledge and the arts. The earliest ancestors of the Vichitra Veena include the Ekatantri Veena, a single-stringed instrument mentioned in ancient texts, and the Ghoshwati or Brahma-Veena, both of which were played with a sliding technique. These instruments were prevalent in the Indian subcontinent, particularly in the northern regions, and played a significant role in the development of classical music. Over the centuries, the design and construction of the veena evolved, incorporating additional strings, larger resonators, and more elaborate ornamentation. By the medieval period, several distinct types of veenas had emerged, each associated with different musical traditions and regions. The Rudra Veena, for example, became prominent in the Dhrupad tradition, while the Saraswati Veena was favored in South Indian Carnatic music. The Vichitra Veena, as a modern descendant of these ancient instruments, is believed to have taken its present form in the late 19th or early 20th century, though its exact origins are difficult to pinpoint.

The instrument was historically known as the “Batta Been,” a reference to the “batta” or stone used to slide along the strings. Its development is often attributed to musicians and instrument makers who sought to expand the expressive capabilities of the veena by eliminating frets and introducing a sliding technique. This innovation allowed for greater melodic flexibility and the ability to execute intricate ornamentations that are central to Indian classical music. Throughout its history, the Vichitra Veena has been associated with North Indian classical music, particularly the Dhrupad tradition. However, its use declined in the early 20th century as other instruments, such as the sitar and sarod, gained popularity. The instrument’s demanding technique and large size contributed to its relative obscurity, and for a time, it was at risk of disappearing altogether.

A revival of interest in the Vichitra Veena occurred in the mid-20th century, thanks to the efforts of dedicated musicians such as Ustad Abdul Aziz Khan and Pandit Lalmani Misra. These artists not only preserved the traditional repertoire but also expanded the instrument’s possibilities by adapting it to new styles and compositions. Their work ensured that the Vichitra Veena remained a vital, if rare, component of India’s musical landscape.

Construction and Physical Structure

The construction of the Vichitra Veena is a testament to the skill and artistry of Indian instrument makers. Its design combines functionality with aesthetic beauty, resulting in an instrument that is both visually striking and acoustically sophisticated. The primary materials used in its construction are wood and gourd, with additional components made from horn, ivory, or synthetic substitutes. The main body of the Vichitra Veena consists of a long, flat wooden plank, typically measuring around three feet in length and six inches in width. This plank, or “dand,” serves as the foundation for the instrument and supports the strings, bridges, and resonators. The wood used is often toon or teak, chosen for its strength, resonance, and ability to withstand the tension of the strings. At each end of the plank are large, spherical resonators made from dried gourds. These “tumba” are hollowed out and attached securely to the underside of the plank, providing the primary means of sound amplification. The gourds are often decorated with intricate carvings or inlaid with ivory or celluloid, adding to the instrument’s visual appeal. The ends of the plank may be carved into the shapes of peacock or swan heads, further enhancing the instrument’s artistic value.

The Vichitra Veena is equipped with multiple sets of strings. The main melody strings, usually four in number, run the length of the plank and are anchored at one end by tuning pegs and at the other by a tailpiece. These strings are made of steel or brass and are responsible for producing the primary melodic content. In addition to the melody strings, there are several drone strings, known as “chikaris,” which are played openly to provide a rhythmic and tonal foundation. The number of drone strings can vary, but there are typically two to five. Beneath the main strings are thirteen sympathetic strings, which are tuned to the notes of the raga being performed. These strings are not played directly but vibrate in response to the main strings, enriching the instrument’s sound with additional overtones and sustain. The sympathetic strings are anchored at one end by a small bridge and at the other by fine tuning pegs, allowing for precise adjustment of their pitch. The bridges of the Vichitra Veena are critical to its sound production.

The main bridge, located near the center of the plank, supports the melody and drone strings and is made of horn, wood, or synthetic materials. The curvature and angle of the bridge, known as “jowari,” determine the instrument’s tonal quality, with adjustments allowing for either a buzzing, overtone-rich sound or a clearer, more focused tone. A secondary bridge supports the sympathetic strings, ensuring that they are properly positioned and able to vibrate freely. The instrument is played using a combination of plectrums and a sliding object. The right hand wears two wire plectrums, or mizrabs, on the index and middle fingers to pluck the melody strings, while the little finger is used to strike the drone strings. The left hand holds a smooth, polished object—traditionally a glass ball or stone, called the “batta”—which is moved along the strings to vary the pitch. This technique allows for continuous glissando and intricate ornamentation, essential features of Indian classical music. The Vichitra Veena is typically placed on the floor in front of the player, who sits cross-legged. The instrument’s size and weight require a stable playing position, and the player must develop considerable skill and dexterity to master its technique. The strings are often lubricated with coconut oil to reduce friction and facilitate smooth sliding of the batta.

The construction of the Vichitra Veena is not standardized, and individual instruments may vary in size, shape, and decoration. This variability allows for experimentation and personalization, with musicians and instrument makers collaborating to achieve the desired sound and aesthetic. The craftsmanship involved in making a Vichitra Veena is highly specialized, requiring years of experience and a deep understanding of acoustics and materials.

Types and Variants

While the Vichitra Veena is itself a distinct type of veena, it exists within a broader family of Indian string instruments that share certain characteristics. The primary variants are distinguished by differences in construction, playing technique, and regional association. The most closely related instrument is the Chitra Veena, also known as Gottuvadhyam, which is prominent in South Indian Carnatic music. Like the Vichitra Veena, the Chitra Veena is fretless and played with a sliding object, but it differs in its body shape, string arrangement, and repertoire. The Chitra Veena typically has a larger number of strings and a different tuning system, reflecting the distinct musical traditions of South India. Within the Hindustani tradition, the Vichitra Veena is sometimes compared to the Rudra Veena, another ancient instrument with a long, fretless body and large resonating gourds. However, the Rudra Veena is equipped with fixed frets and is played using a different technique, involving the pressing of strings against the frets rather than sliding. The Vichitra Veena’s fretless design and use of a batta set it apart as a unique variant within the veena family.

There are also minor variations in the construction and decoration of the Vichitra Veena itself. Some instruments feature more elaborate carvings or inlays, while others have different numbers of strings or alternative materials for the bridges and resonators. The choice of wood, the size of the gourds, and the design of the tuning pegs can all influence the instrument’s sound and appearance. The Vichitra Veena has inspired modern adaptations and experimental instruments, as musicians seek to expand its expressive possibilities. These innovations may include the use of synthetic materials, alternative tuning systems, or electronic amplification. While traditional craftsmanship remains highly valued, contemporary makers are exploring new approaches to ensure the instrument’s continued relevance and accessibility.

Characteristics of the Vichitra Veena

The Vichitra Veena is distinguished by several key characteristics that define its sound, playing technique, and role within Indian classical music. Its most notable feature is its fretless design, which allows for continuous, unbroken slides between notes. This capability is essential for the execution of meend, gamak, and other ornamentations that are central to the expression of Indian ragas. The absence of frets also enables the performer to explore microtonal variations and subtle pitch inflections, adding depth and nuance to the music. The instrument’s sound is characterized by its deep, resonant tone and rich harmonic content. The combination of melody, drone, and sympathetic strings produces a complex, layered sound that envelops the listener. The sympathetic strings, in particular, contribute to the instrument’s sustain and overtones, creating a shimmering, meditative quality that is both soothing and mesmerizing. The playing technique of the Vichitra Veena is highly specialized and demanding. The use of a batta to slide along the strings requires precise control and coordination, as the player must maintain consistent pressure and movement to achieve the desired pitch and timbre. The right hand’s use of mizrabs to pluck the strings adds rhythmic complexity and articulation, while the little finger’s engagement with the drone strings provides a continuous tonal backdrop.

The instrument’s repertoire is rooted in the Dhrupad tradition of North Indian classical music, which emphasizes purity of pitch, slow tempo, and meditative exploration of ragas. However, innovative musicians have adapted the Vichitra Veena for other genres, such as Khyal and Thumri, demonstrating its versatility and expressive potential. The instrument’s capacity for sustained notes and dynamic range makes it well-suited to both solo performance and accompaniment. The Vichitra Veena’s construction allows for considerable variation in sound and appearance. The choice of materials, the design of the bridges, and the tuning of the strings all influence the instrument’s tonal quality. Musicians and instrument makers often collaborate to customize the instrument to suit individual preferences and performance requirements. Despite its many virtues, the Vichitra Veena remains a rare and challenging instrument. Its size, weight, and demanding technique have limited its popularity, and only a small number of musicians have mastered its intricacies. Nonetheless, those who do play the Vichitra Veena are often regarded as virtuosos, admired for their dedication and artistry.

Playing Techniques and Sound Modifications

The Vichitra Veena is renowned for its unique, fretless design and the distinct playing technique that sets it apart from other stringed instruments in Indian classical music. To play the Vichitra Veena, the musician sits with the instrument placed horizontally in front of them, supported by two large, detachable gourds that act as resonators. The main body, or dand, is a long, hollow wooden bar without any frets, allowing for a continuous gliding motion along the strings. The right hand wears wire plectrums, known as mizrabs, on the index and middle fingers to pluck the melody strings, while the little finger is often used to strike the drone strings, or chikaris. The left hand holds a smoothly polished glass ball or stone, called the batta, which is slid along the main strings to produce notes. This sliding technique is akin to that used in slide guitar, but with the added complexity of Indian classical ornamentation. The batta allows for intricate meends (glides), gamaks (oscillations), and andolans (slow oscillations), giving the instrument its characteristic expressive quality.

Sound modification is achieved through several means. The angle and curvature of the bridge, known as the jowari, can be adjusted to either promote a buzzing, overtone-rich sound (open jowari) or a clearer, more singing tone (closed jowari). The choice of string gauge, material, and tuning further influences the tonal palette. The Vichitra Veena typically features four to six main playing strings, five drone strings, and up to thirteen sympathetic strings (tarabs) that resonate in sympathy with the played notes, enriching the overall sound with a shimmering sustain and complex overtones. Coconut oil is sometimes applied to the strings to reduce friction and facilitate smooth sliding of the batta. The instrument’s lack of frets demands exceptional precision from the player, as even a slight deviation in the batta’s position can result in off-pitch notes. This makes fast passages challenging, but the Vichitra Veena excels in slow, meditative renditions where the beauty of its tone and the depth of its glides can be fully appreciated.

Famous Compositions

The repertoire for the Vichitra Veena has historically been closely linked with the Dhrupad tradition, one of the oldest forms of Hindustani classical music. Dhrupad compositions, known for their solemn and spiritual character, suit the deep, resonant voice of the Vichitra Veena. Traditionally, the instrument was used to accompany vocalists in Dhrupad performances, emphasizing slow, deliberate phrasing and minimal ornamentation.

Lalmani Misra, in the 20th century, played a pivotal role in expanding the Vichitra Veena’s repertoire. He developed the Misrabani style, which introduced intricate rhythmic patterns and allowed for greater melodic complexity. Misrabani compositions for the Vichitra Veena include elaborate alap (improvised introduction), jod (rhythmic bridge), and jhala (fast-paced conclusion) sections, as well as structured bandishes (composed pieces) in various talas (rhythmic cycles) such as Jhoomra, Dhamar, and Teentaal.

Gopal Shankar Misra, Lalmani Misra’s son, further enriched the instrument’s repertoire by adapting popular ragas and creating new compositions that showcased the expressive range of the Vichitra Veena. His performances often featured ragas like Yaman, Bhairavi, and Malkauns, demonstrating the instrument’s ability to convey both lyrical and dramatic moods.

Most Influential Players

The Vichitra Veena has always been a rare instrument, and its lineage of master players is correspondingly select. Among the most influential figures is Lalmani Misra, who is credited with reviving the instrument in the 20th century. His innovations in playing technique, string arrangement, and composition not only preserved the Vichitra Veena but also elevated its status in the world of Indian classical music. Gopal Shankar Misra, Lalmani Misra’s son, is another towering figure. He was instrumental in popularizing the Vichitra Veena on the concert stage and through recordings, bringing its haunting sound to a global audience. His mastery of the instrument and his ability to blend tradition with innovation made him a respected ambassador for the Vichitra Veena. Other notable players include Dr. Gopal Shankar Misra, whose performances and teaching have inspired a new generation of musicians to take up the instrument. Despite its rarity, the Vichitra Veena continues to attract dedicated artists who are committed to preserving and advancing its unique legacy.

Historical Performances or Concerts

The Vichitra Veena’s history is interwoven with the courts and temples of North India, where it was once a favored instrument for accompanying Dhrupad vocalists. Its deep, meditative sound was considered ideal for spiritual and ceremonial occasions. However, as musical tastes shifted and the instrument’s challenging technique limited its popularity, the Vichitra Veena gradually faded from public performance. The 20th century saw a resurgence of interest, largely due to the efforts of Lalmani Misra and his disciples. Notable performances include recitals at major music festivals in India, such as the All India Radio Sangeet Sammelan and the Tansen Samaroh in Gwalior. These concerts introduced wider audiences to the Vichitra Veena’s distinctive voice and helped spark renewed appreciation for its artistry. Gopal Shankar Misra’s international tours and recordings further expanded the instrument’s reach. His performances in Europe and North America were met with critical acclaim, and his recordings remain reference points for both students and connoisseurs of Indian classical music.

Maintenance and Care

The Vichitra Veena, with its intricate construction and delicate materials, requires meticulous maintenance to preserve its sound quality and longevity. The body is typically crafted from seasoned woods such as tun, teak, or sisam, which must be protected from extremes of temperature and humidity to prevent warping or cracking. The large gourds used as resonators are particularly sensitive and should be handled with care to avoid breakage. Regular cleaning is essential to remove dust and prevent the buildup of grime on the strings and body. The strings themselves, made of brass, steel, or bronze, must be wiped down after each use to prevent corrosion. They should be replaced periodically to maintain optimal tone and playability. The bridges, often made of ivory or horn, can develop grooves from the constant abrasion of the strings. These grooves must be monitored and, if necessary, the bridge surface should be sanded and reshaped by a skilled luthier to restore the desired jowari and sound quality.

The batta, or sliding stone, should be kept smooth and free of nicks or rough spots to ensure effortless gliding along the strings. Some musicians apply a small amount of coconut oil to the strings to reduce friction and prolong their life. Tuning the Vichitra Veena is a delicate process, as the instrument’s many strings must be adjusted to precise pitches, often according to the raga being performed. The sympathetic strings, in particular, require careful tuning to resonate correctly and enhance the overall sound.

Interesting Facts and Cultural Significance

The Vichitra Veena is one of the few surviving fretless zithers in Indian classical music, and its design is believed to have evolved from ancient instruments mentioned in Vedic texts, such as the Ghoshwati or Brahma Veena. Its name, which means “peculiar” or “wondrous” veena, reflects both its unusual appearance and its distinctive sound. Unlike the more commonly seen sitar or sarod, the Vichitra Veena’s fretless design allows for an unparalleled range of microtonal expression, making it especially well-suited for the nuanced ornamentation of Indian ragas. The instrument’s sympathetic strings, a hallmark of Indian luthiery, create a rich, resonant soundscape that envelops the listener. The Vichitra Veena has historically been associated with the Dhrupad tradition, which emphasizes spiritual depth and meditative exploration. Its deep, sonorous voice is said to evoke a sense of tranquility and introspection, making it a favored instrument for devotional music and temple rituals.

Despite its decline in popularity during the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Vichitra Veena has experienced a modest revival in recent decades, thanks to the dedication of a handful of master musicians and instrument makers. Its rarity and the demanding nature of its technique have made it a symbol of artistic perseverance and mastery. The instrument’s cultural significance extends beyond music. The peacock and swan motifs often carved into its ends are symbols of beauty and grace in Indian art, further enhancing its status as a cultural treasure.

FAQ

What is the construction and material used in the Vichitra Veena?

The Vichitra Veena is built with a large wooden body made of teak or tun wood, featuring two resonating gourds at each end. It has a fretless flat surface and uses a set of main, drone, and sympathetic strings made of metal. The bridge is typically made from animal bone or synthetic materials. The instrument is played using a slide and plectrums.

What are the different types and musical features of the Vichitra Veena?

Though the Vichitra Veena does not have many known variants, it is unique for its gliding, meend-heavy sound produced without frets. It has four main playing strings, three drone strings, and eleven to thirteen sympathetic strings. Its tonal quality is deep, resonant, and ideal for slow, expressive raga development. It is used mainly in Hindustani classical music.

What is the history and application of the Vichitra Veena in Indian music?

The Vichitra Veena evolved from ancient veenas and became popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was championed by musicians like Lalmani Misra. Despite being rare today, it is known for its meditative sound and is used in dhrupad and alap performances. Its role is mostly solo or for spiritual music contexts.

Links

Links

References

Other Instrument

Categories