Benju

Plucked Instruments

Asia

Between 1001 and 1900 AD

Video

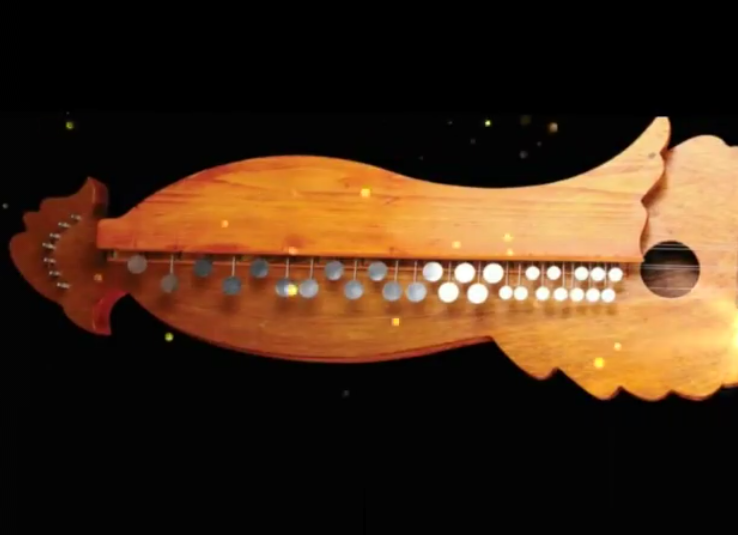

The Benju, also known as Benjo, is a unique musical instrument that belongs to the zither family. It is distinguished by its integration of a keyboard and is widely used in Sindhi and Balochi music. The instrument produces a rich overtone, creating a mesmerizing sound that has become an essential part of folk music traditions in the regions of Sindh and Balochistan. Its captivating tonal quality makes it a central feature in various musical performances, ranging from solo acts to ensemble settings. The Benju’s ability to blend with other instruments like the dholak, tambura, and suroz further enhances its versatility and appeal in traditional and contemporary music.

Type of Instrument

The Benju is classified as a type of zither, specifically a keyboard-fitted zither. Zithers are stringed instruments where the strings run parallel to the soundboard. In the case of the Benju, it combines the features of a string instrument with those of a keyboard, allowing for chromatic scales and melodic versatility. This hybrid nature places it in a unique category among traditional instruments. Its design allows it to function both as a melodic and harmonic instrument, making it suitable for a wide range of musical styles.

Origins and Evolution

The history of the Benju is deeply intertwined with cultural exchanges across continents. It traces its origins to Japan, where it was initially introduced as the Taishōgoto or Nagoya harp—a simple children’s toy. In the early 20th century, Japanese sailors brought this instrument to Karachi, Pakistan. Over time, the Baloch community adopted and modified this toy into a sophisticated musical instrument tailored to their cultural needs.

The modifications included enlarging its body for better resonance, increasing the number of strings to six, and adding rows of keys for chromatic scales. These changes transformed the Benju into an integral part of Baluchi folk music. By the mid-20th century, it had gained widespread popularity across Pakistan and Iran, becoming a staple in rural weddings, urban performances, and even radio broadcasts. The Benju’s journey from Japan to South Asia highlights its role as a product of cultural fusion. While its roots lie in East Asia, its transformation into a traditional Baluchi instrument underscores the adaptability and ingenuity of local musicians. Today, it is most commonly associated with the regions of Sindh and Balochistan in Pakistan but has also found audiences in Iran and beyond.

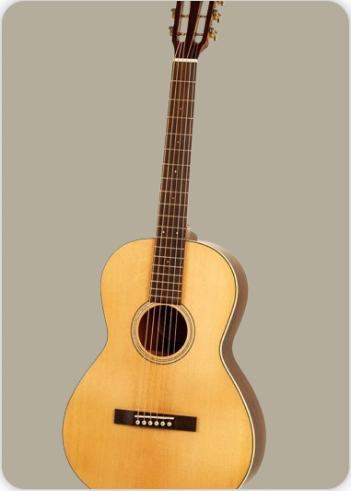

Construction and Design

The Benju is approximately one meter long and 10–12 cm wide, with a soundbox about 5 cm high. It features six strings arranged in pairs: two drone strings (bordun) tuned to tonic intervals like C and G or F, and four melody strings tuned in unison or chromatically. The strings are played using a wooden or plastic plectrum held in the right hand, while the left hand operates metal keys to change pitch. The instrument’s design allows for chromatic scales ranging from G to A or B-flat. Its compact size and lightweight construction make it portable yet robust enough for dynamic performances. Modern adaptations have incorporated electric pickups for amplification, broadening its use in contemporary music settings.

Types of Benju

While the traditional six-stringed Benju remains the most common variant, there are other adaptations based on regional preferences and individual creativity:

Five-Stringed Variant: Popularized by virtuosos like Ustad Noor Bakhsh, this version features fewer strings but compensates with electric amplification.

Electric Benju: Equipped with pickups and amplifiers for louder performances in urban settings.

Traditional Acoustic Benju: Retains its original design without modern enhancements.

These variations demonstrate how musicians have adapted the instrument to suit different performance contexts while preserving its core characteristics.

Characteristics

The Benju is renowned for its rich tonal quality and melodic flexibility. Its sound is characterized by overtones and shadow notes that create an ethereal effect. The combination of drone strings with fretted melody strings allows for both rhythmic accompaniment and intricate melodic lines. Despite its versatility, one limitation is its inability to produce glissandos or lyrical inflections typical of regional vocal styles. However, this shortcoming is offset by its capacity for melismatic virtuosity facilitated by soft keys. In terms of playability, the division of labor between hands—one strumming while the other presses keys—ensures dynamic control over rhythm and melody. This makes it equally suitable for solo performances and ensemble arrangements.

Cultural Significance

The Benju holds immense cultural value in Sindhi and Balochi music traditions. It serves as both an accompaniment instrument and a solo performer’s tool during weddings, festivals, and other social gatherings. Its presence in regional TV programs further underscores its role as a cultural ambassador. In recent years, musicians like Ustad Noor Bakhsh have brought international attention to the Benju through global tours. Their efforts have not only preserved this traditional instrument but also introduced it to new audiences worldwide.

Playing Techniques and Sound Modifications

The Benju is a keyboard-fitted zither that requires both hands for its operation. The left hand presses the metal keys to modify the pitch of the strings, while the right hand strums the strings using a wooden or plastic plectrum. This dual-hand technique allows for intricate melodic and rhythmic patterns. The instrument is tuned chromatically, typically from G to A, B flat, or B, with six strings divided into drone and melody functions. Strings 1 and 2, as well as 5 and 6, serve as drone strings tuned to the tonic and fifth or fourth (e.g., C and G or F), while the middle strings (3 and 4) are tuned in unison to F or G for melodic play.

Sound modifications are achieved by employing melismatic phrasing and ornamentation, facilitated by the soft keys of the instrument. However, the Benju has limitations in executing glissandos and lyrical inflections typical of regional music styles. Despite this, its rich overtone-laden sound compensates for these shortcomings. In modern adaptations, some players have electrified their Benjus using pickups and amplifiers, further expanding its sonic capabilities. For instance, Ustad Noor Bakhsh uses a five-stringed Benju with an electric pickup system powered by a car battery and solar panel, showcasing the ingenuity of Baluchi musicians.

Applications in Music

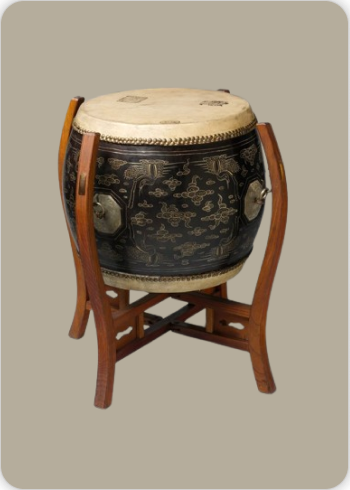

The Benju holds a versatile role in music, particularly in Sindhi and Baluchi traditions. It is often played as a solo instrument accompanied by percussion instruments like the dholak and melodic drones from instruments such as the tambura. Additionally, it is sometimes paired with the Suroz, another traditional Baluchi instrument. Its applications extend beyond folk music to urban settings where its loudness is appreciated in live performances. The Benju is frequently featured in weddings, local festivities, and even on regional radio and television broadcasts. Its adaptability has also made it a staple in contemporary Baluchi music, blending traditional melodies with modern performance contexts. In spiritual contexts, the Benju complements Sufi-inspired music with its repetitive melodic motifs that evoke meditative states. Its sound resonates deeply with themes of love, loss, and spirituality in Baluchi culture. Furthermore, it has been used to accompany healing rituals such as Zar and Gawati ceremonies.

Most Influential Players

Several musicians have significantly contributed to the popularity of the Benju:

Ustad Noor Bakhsh: Born in Pakistani Baluchistan, Noor Bakhsh began playing the Benju at age 12. Known for his innovative techniques and electrified five-stringed Benju setup, he has gained international acclaim through performances at major festivals like Roskilde Festival during his 2023 European tour. His album “Jingul” highlights his unique style that blends traditional folk tunes with experimental elements.

Abd-ur-Rahmân Surizehi: Hailing from Iranian Baluchistan but now residing in Norway, Surizehi is regarded as one of the greatest performers of the Benju. His mastery of this instrument has earned him global recognition.

Bilawal Belgium: A prominent Benju player from Mirpur Khas in Sindh who continues to contribute to its legacy through his performances.

These musicians have not only preserved traditional playing techniques but also introduced innovative methods that have expanded the instrument’s reach globally.

Maintenance and Care

Proper maintenance is crucial for preserving the quality and longevity of a Benju. The wooden body needs regular cleaning to prevent dust accumulation that could affect its resonance. Strings should be inspected frequently for signs of wear or rust and replaced when necessary to maintain consistent sound quality. The metal keys require occasional lubrication to ensure smooth operation during play. If electrified components are used, such as pickups or amplifiers, they must be checked regularly for functionality. In regions with extreme climates like Baluchistan, tuning adjustments may be needed to account for temperature-induced changes in string tension. Storage conditions are equally important; the Benju should be kept in a dry environment away from direct sunlight to prevent warping of its wooden body. A padded case is recommended for transportation to protect it from physical damage.

Cultural Significance

The Benju holds profound cultural importance among Sindhi and Baluchi communities. Introduced as a Japanese toy instrument (taishogoto) in Karachi during the early 20th century by sailors, it was transformed into a vital element of regional musical traditions through local modifications. Over time, it became an emblematic instrument reflecting the cultural identity of these regions. In Baluchistan, where music often intertwines with oral storytelling traditions, the Benju serves as a medium for expressing themes of love (dastanag), loss (zahiroh), and spirituality. Its role extends beyond entertainment; it is integral to social gatherings such as weddings and religious ceremonies.

The instrument also symbolizes resilience and creativity among Baluchi people who adapted it despite limited resources. By modifying its structure—adding more strings, keys, and even electrifying it—they turned a simple toy into an iconic musical tool. In recent years, efforts by anthropologists like Daniyal Ahmed have brought global attention to the Benju through documentation and promotion of artists like Ustad Noor Bakhsh. This international recognition underscores its evolving significance not only as a cultural artifact but also as a dynamic element of world music heritage.

Through its rich history and multifaceted applications in music, spirituality, and social life, the Benju continues to be a testament to the enduring cultural vibrancy of Sindhi and Baluchi communities.

FAQ

What is the history of the Benju musical instrument?

The Benju originated in South Asia, particularly in Pakistan and India. It is a modified version of the Japanese taishogoto, adapted for local music. The instrument gained popularity in folk and street music due to its ease of play. It is commonly used in Sindhi and Balochi music traditions.

What materials are used in constructing a Benju?

The Benju is typically made from wood for the body and metal for the strings. The keys are usually plastic or wood, similar to a typewriter mechanism. Some modern versions feature electronic amplification for enhanced sound projection. Traditional Benjus are handcrafted for a resonant and warm tone.

What are the key features of the Benju?

The Benju is a stringed keyboard instrument with metal strings played using keys. It produces a bright, melodic sound and is often used in folk and devotional music. Its compact size and easy playability make it popular among street musicians. Some versions come with built-in pickups for electronic amplification.

Links

Links

References

Other Instrument

Categories